Chapter 14. Marriage and Family

14.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

Marriage and family are key structures in most societies. While the two institutions have historically been closely linked in Canadian culture, their connection is becoming more complex. The relationship between marriage and family is often taken for granted in the popular imagination but with the increasing diversity of family forms in the 21st century their relationship needs to be reexamined.

What is marriage? Different people define it in different ways. Not even sociologists are able to agree on a single meaning. A straightforward definition of marriage is: a legally recognized social contract between two people, based on a sexual or intimate relationship, and implying cohabitation and a permanence of the union. But to create a more inclusive definition, sociologists might also consider variations, such as whether a formal legal union is required (think of common-law marriage and its equivalents), whether a sexual relationship is necessary (consider permanent intimate relationships between asexual individuals), or whether more than two people can be involved (consider polygamy, polyandry or polyamory). Other variations on the definition of marriage might include whether spouses are of opposite sexes or the same sex (regardless of local laws governing same-sex marriage), and how one of the traditional expectations of marriage, to produce children, is relevant to the question.

Interestingly, a court case in 1867, at the time of Confederation, might provide the basis for a truly “traditional” Canadian definition of marriage. In the 19th century marital unions between European fur traders and Aboriginal women were common, but also foreshadowed some of the complexity sociologists confront in defining marriage today. European authorities, especially religious authorities, tended to define legitimate marriage based on European practices — monogamy, insolubility, holy sacrament, etc. — and insisted that Aboriginal people conform to them. There were also fears about “mixing blood” and racial “degeneration.” But in a context where marriage with Aboriginal women provided useful socioeconomic alliances, acculturation into frontier life, as well as the “many tender ties” of domestic life, European men often accepted Aboriginal practices, which included payment of bride price, polygamy, and divorce depending on the nation (Van Kirk, 2002; 1980). They were married “en façon du pays” or by the “custom of the country.”

This was the case with William Connolly and his Cree wife Suzanne, who married in 1803 at Rivière-aux-Rats (in now northern Manitoba), according to Cree customs, and lived together for 28 years, having 6 children. William then married his cousin Julia Woolrich in a Catholic ceremony. When William died and his estate went to Julia, one of his sons by Suzanne argued in court that the second marriage was null because William was still married to his mother. The question was whether their Cree marriage ceremony was legally valid, or, what definition of marriage applied to the inheritance of William’s estate. The court recognized the Cree marriage customs as valid and binding (Walter, 2017). The ruling of Connolly v Woolrich therefore defined marriage according to components of both European and Aboriginal marriage, emphasizing local custom and social recognition. As Van Kirk (2002) summarizes, “a marriage was defined as being openly recognized and characterized by mutual consent, cohabitation, and public repute as husband and wife.”

Sociologists are interested in the relationship between the institution of marriage and the institution of family because, historically, marriages are what legally and normatively create a family, and families are a primary social unit upon which society is built. Both marriage and family create status roles that are recognized, sanctioned and regulated by society.

So what is a family? Léon Gérin’s (1863-1951) early research on the family in transition in Quebec, noted the emerging dominance of the nuclear or “particularist” family in the late 19th century as families adapted to the urbanized, industrial economy (Comacchio, 2000). The nuclear ideal of a husband, a wife, and two biological children — maybe even a pet — served as the model for the “traditional” Canadian family for most of the 20th century. As Gérin noted, it supplanted the previous “traditional” stem family, which was generally large, rural, multi-generational and self-sufficient, in which one of the children married and remained in the family home while other siblings moved away. But what about families that deviate from these models, such as the single-parent household, the blended family or the homosexual couple, with or without children? Can a definition of family be formulated to include them as well?

The question of what constitutes a family is a prime area of debate in family sociology, as well as in contemporary politics and religion. Social conservatives tend to define the family in terms of a heterosexual, nuclear family structure with each family member filling a certain role (like father, mother, or child). As former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper put it, “I have no difficulty with the recognition of civil unions for nontraditional relationships but I believe in law we should protect the traditional definition of marriage” (Globe and Mail, 2010). Others define family much more broadly as a group of intimates tied together by bonds of love and commitment. American Talk show host Oprah Winfrey defines family as “a marvelous, occasionally messy collection of partners, parents, exes, siblings, babies, and best friends—all bonded by that most powerful glue…love” (Winfrey, 2019).

Navigating between these different definitions, sociologists seek a substantive definition that can distinguish family groups from non-family groups. Rather than relying on definitions borrowed from specific religious or cultural traditions, they tend to define family more in terms of the manner in which members relate to one another. Therefore, family can be defined as a socially recognized group joined by blood relations, marriage, or adoption, that forms an emotional connection and serves as an economic unit of society.

Based on Georg Simmel’s (1971 (1908)) distinction between the form and content of social interaction (see Chapter 7. Groups and Organizations), sociologists can analyze the family as a social form that comes into existence around five different contents or interests: sexual activity, economic cooperation, reproduction, socialization of children, and emotional support. As one might expect from Simmel’s analysis, the types of family form in which all or some of these contents are expressed are diverse: nuclear families, polygamous families, extended families, same-sex parent families, single-parent families, blended families, and zero-child families, etc. However, the forms that families take are not random; rather, these forms are determined by cultural traditions, social structures, economic pressures, and historical transformations. They also are subject to intense moral and political debate about the definition of the family, the “decline of the family,” or the policy options to best support the well-being of families.

Marriage Patterns as Social Forms

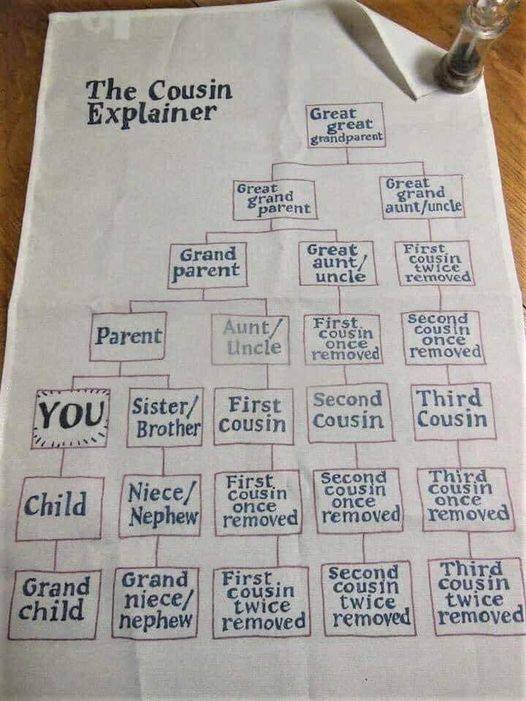

Contemporary North Americans typically equate marriage and cohabitation with monogamy, when someone is married to only one person at a time. Following Simmel’s sociological approach above, monogamy is a social form or relationship pattern that regulates sexual activity as a content of social relationships. It has consequences for the social forms that the other contents of “family” assume: economic cooperation, reproduction, socialization of children, and emotional support. In fact, who can marry whom, and who is permitted to have sex with whom, are key variables in distinguishing various types of kinship system, systems of social organization based on real or putative family ties (Carston, 1998). The most basic rule for all societies is the incest taboo — an individual may not have sex with or marry someone who is a close blood relative — but beyond this constraint there is great variation in kinship practices (Stebbins, 2013).

In a majority of cultures around the world (78%), polygamy, or being married to more than one person at a time, is accepted (Murdock, 1967), with most polygamous societies existing in Sub-Saharan Africa and Muslim dominant countries (Altman and Ginat, 1996). Instances of polygamy are almost exclusively in the form of polygyny. Polygyny refers to a man being married to more than one woman at the same time. The reverse, when a woman is married to more than one man at the same time, is called polyandry. It is far less common and only occurs in about 1 per cent of the world’s cultures (Altman and Ginat, 1996). While the majority of societies accept polygyny, the majority of people do not practice it. Often fewer than 10% (and no more than 25 to 35%) of men in cultures that accept polygamy have more than one wife. Having multiple wives is a sign of status and wealth for a man, but he usually must have the wealth and status before he can have more than one wife (Altman and Ginat, 1996).

In Canada, polygamy is considered by most to be socially unacceptable and it is illegal. The act of entering into marriage while still married to another person is referred to as bigamy and is prohibited by Section 290 of the Criminal Code of Canada (Minister of Justice, 2014). In precolonial times however, many Aboriginal peoples practiced polygyny, often as a means of establishing formal ties and mutual obligations between different groups. In societies where kinship is the dominant organizing structure, marital ties are central to economic accumulation and political alliances. Having more than one wife was an indicator of a man’s status and also had practical benefits for the family unit, as the wives’ labour was valuable in maintaining the household, accumulating wealth and producing children. Leading men among the Cree or Blackfoot, for example, often married sisters (the practice of sororal polygyny) or the wife of a deceased brother, usually in consultation and agreement with their first wife (Carter, 2008). Polygyny was seen to benefit both husbands and wives. Polyandry, while seemingly rare, was reported among the Cherokee, Seneca, and Pawnee nations (among others); sometimes as a case of one wife being married to brothers (fraternal polyandry), or sometimes as an indicator of a woman’s high status in possessing land or resources (Stebbins, 2013; Broberg, 1984; Lesser, 1930).

The displacement of Aboriginal marriage traditions was one of the effects of colonialism. Legal, political, and missionary authorities determined that lifelong monogamy in the tradition of the Christian religion and English common law was the marriage model that symbolized the proper differences between the sexes and set the foundation for the way both sexes were to behave (Carter, 2008).

The criminalization of polygamy in 1890 was in fact a response to the immigration of polygamous Mormon sects to Alberta. Polygamy in Canada is often associated with those of the Mormon faith, although in 1890 the Mormon Church officially renounced polygamy. Fundamentalist Mormons, on the other hand, such as those in Bountiful, B.C. who follow the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS), still hold tightly to the historic Mormon beliefs and practices and allow polygamy in their sect.

In practice though, as Carter (2008) shows with regard to prairie Aboriginal communities, mandatory monogamy was applied to Aboriginal people through various coercive means as a way to “civilize” them, simultaneously undermining the traditional authority structures and status of leading men and the relative sexual freedoms and privileges of Aboriginal women. Lifelong monogamous “marriage was part of the national agenda in Canada—the marriage ‘fortress’ was established to guard the [Canadian] way of life.”

Residency and Lines of Descent

Another way in which the social forms of family differ is by practices determining lineage and inheritance. Sociologists identify different types of families based on how one enters into them. A family of orientation refers to the family into which a person is born. A family of procreation describes one that is formed through marriage. But where one ends up living, whose family one belongs to, which relations are closest or more distant, or who is regarded as blood kin (i.e.,interdicted by the incest taboo) differs by kinship system. Societies vary when it comes to determining who is a member of one’s family who one can go to for family support.

When considering their lineage, most North Americans look to both their father’s and mother’s sides. Both paternal and maternal ancestors are considered part of one’s family and inheritance passes from both sides to both male and female children. This pattern of tracing kinship is called bilateral descent. Note that kinship can be based on blood, marriage, or adoption. Sixty per cent of societies, mostly modernized nations, follow a bilateral descent pattern. Unilateral descent (the tracing of kinship through one parent only) is practiced in the other 40% of the world’s societies, with high concentration in pastoral cultures (O’Neal, 2006).

There are three types of unilateral descent: patrilineal, which follows the father’s line only; matrilineal, which follows the mother’s side only; and ambilineal, which follows either the father’s only or the mother’s side only, depending on the situation. In patrilineal societies, such as those in rural China and India, only males carry on the family surname. This gives males the prestige of permanent family membership while females are seen as only temporary members (Harrell, 2001). North American society assumes some aspects of partrilineal decent. For instance, most children assume their father’s last name even if the mother retains her birth name.

In matrilineal societies, inheritance and family ties are traced to women. Matrilineal descent is common in Native American societies, notably among the Iroquois, Hopi, Navajo, Haida, Tsimshian and Tlingit nations. In these societies, children are seen as belonging to the women and, therefore, one’s kinship is traced to one’s mother, grandmother, great grandmother, and so on (Mails, 1996). In ambilineal societies, which are most common in South East Asian countries, parents may choose to associate their children with the kinship of either the mother or the father. This choice may be based on the desire to follow stronger or more prestigious kinship lines or on cultural customs, such as men following their father’s side and women following their mother’s side (Lambert, 2009).

Tracing one’s line of descent to one parent rather than the other can be relevant to the issue of residence. In many cultures, newly married couples move in with, or near to, family members. In a patrilocal residence system it is customary for the wife to live with (or near) her husband’s blood relatives (or family of orientation). Patrilocal residence is a key structure of patriarchal societies because it is a means by which women can be controlled and transferred like property or assets between their father’s and husband’s families. In particular, the control of women’s sexuality and fertility is a means of ensuring paternity and paternal lineage. While it is relatively easy to know who a child’s biological mother is, it is not so easy to be certain that children are biological offspring of the father. Women also become outsiders in the home and community, disconnected from their own blood relatives. In China, where patrilocal and patrilineal customs are common, the written symbols for maternal grandmother (wáipá) are separately translated to mean “outsider” and “women” (Cohen, 2011).

In matrilocal residence systems, it is customary for the husband to live with his wife’s blood relatives (or her family of orientation). Land and property are held by the maternal family and both men and women hold status through their maternal clan affiliation. Among the precolonial Iroquois nations for example, maternal clans lived in longhouses in the Great Lakes region and husbands joined their wives families. Clan membership as well as all goods, titles and rights passed through the maternal lineage. “Thus, in precolonial Iroquois society, a given household could be expected to consist of several nuclear families: a senior woman and her husband, her daughters and unmarried sons, her daughters’ husbands, and her daughters’ children” (Parmenter, 2010). Interestingly, in matrilineal/matrilocal societies there can be no illegitimate children, or questions about children’s legitimate lineage, because all children have mothers (Stone, 1976).

If patrilineal/patrilocal societies are patriarchal, are matrilineal/matrilocal societies “matriarchal”? They are not matriarchal in the sense of being the opposite of patriarchies, societies where women control and hold power over men. In matriarchal structures, typically both grandmothers and uncles hold power and governance is conducted through discussion, consensus and agreement of members (Christ, 2016). This was the case with consensus decision making in the “sachem” structure of the Iroquois Confederacy. These societies were matriarchal in the sense that elder women were heads of the family and selected male chiefs as sachems who represented the clans in the general council (Jefferson, 1994). Matriarchy in this sense refers to relatively egalitarian, small scale agricultural societies in which mothering is recognized as the central unifying structure (Goettner-Abendroth, 2009).

Confluent Love and Cohabitation

With single parenting and cohabitation (when a couple shares a residence but not a marriage) becoming more acceptable in recent years, people may be less motivated to get married. In a recent survey, 53% of Canadian respondents said that “marriage is simply not necessary” (Angus Reid Institute, 2017). Nearly three-quarters of 18-34-year-olds in the survey had never been married, and one-in-six in this group reported that they were not inclined to ever marry.

As Simmel (1971 (1908)) argues, before social forms become formalized and institutionalized, they remain in a process of reciprocity and mutual attunement. This also applies to new social forms of marriage and the family in the social flux of late modernity. Giddens (1992) analyses the emergence of confluent love as a new, non-institutionalized form of intimacy. He describes this as a form of “pure relationship;” not “sexually pure” but entered into purely “for its own sake,” without ulterior purposes like forging family alliances, satisfying parental expectations, having children, or establishing respectability in a career path, etc. Couples enter into a relationship that lasts only as long as the satisfaction it brings to both partners. This is a form of relationship which “presumes equality in emotional give and take,” where trust and stability are produced through a process mutual self-disclosure and appreciation of the other’s unique qualities. “Love here only develops to the degree to which intimacy does, to the degree to which each partner is prepared to reveal concerns and needs to the other and to be vulnerable to that other.” Moreover, if regulation of sexuality is a key element in the different types of marital relationship described above, confluent love “makes the achievement of reciprocal sexual pleasure a key element in whether the relationship is sustained or dissolved.” As a result, Giddens notes that while confluent love can be deeply meaningful it is also intrinsically fragile. When the relationship is no longer mutually satisfactory, it dissolves.

Nevertheless, confluent love is a social form appropriate to late modern priorities of individual freedom, self-creation and self-actualization. It gives a specifically late modern shape to individual “contents” or desires for relationship, self-discovery and sexual and emotional intimacy. The institution of marriage is likely to continue, but some previous patterns of marriage will become outdated as new patterns emerge. In this context, cohabitation and confluent love contribute to the phenomenon of people getting formally married for the first time at a later age than was typical in earlier generations (Glezer, 1991). Furthermore, marriage will continue to be delayed as more people place education, career and “experiencing life” ahead of settling down.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

How Do Working Moms Impact Society?

What constitutes a “typical family” in Canada has changed tremendously over the past decades. One of the most notable changes has been the increasing number of mothers who work outside the home. Earlier in Canadian history, most family households consisted of one parent working outside the home and the other being the primary child care provider. Because of traditional gender roles and family structures, this was typically a working father and a stay-at-home mom. Research shows that in 1951 only 21.6% of all women worked outside the home. In 2015, 82% of all women did, and 69.5% of women with children younger than six years of age were employed (Moyser, 2017).

Sociologists interested in this topic might approach its study from a variety of angles. One might be interested in its impact on a child’s development; another sociologist may explore its effect on family income; while a third sociologist might examine how other social institutions have responded to this shift in society. A sociologist studying the impact of working mothers on a child’s development might ask questions about children raised in child care settings outside the home. How is a child socialized differently when raised largely by a child care provider rather than a parent? Do early experiences in a school-like child care setting lead to improved academic performance later in life? How does a child with two working parents perceive gender roles compared to a child raised with a stay-at-home parent? Another sociologist might be interested in the increase in working mothers from an economic perspective. Why do so many households today have dual incomes? Has this changed the income of families substantially? How do women’s dual roles in the household and in the wider economy affect their occupational achievements and ability to participate on an equal basis with men in the workforce? What impact does the larger economy play in the economic conditions of an individual household? Do people view money — savings, spending, debt — differently than they have in the past?

Curiosity about this trend’s influence on social institutions might lead a researcher to explore its effect on the nation’s educational and child care systems. Has the increase in working mothers shifted traditional family responsibilities onto schools, such as providing lunch and even breakfast for students? How does the creation of after-school care programs shift resources away from traditional school programs? What would the effect be of providing a universal, subsidized child care program on the ability of women to pursue uninterrupted careers?

As these examples show, sociologists study many real-world topics. Their research often influences social policies and political issues. Results from sociological studies on this topic might play a role in developing federal policies like the Employment Insurance maternity and parental benefits program, or they might bolster the efforts of an advocacy group striving to reduce social stigmas placed on stay-at-home dads, or they might help governments determine how to best allocate funding for education. Many European countries like Sweden have substantial family support policies, such as a full year of parental leave at 80% of wages when a child is born, and heavily subsidized, high-quality daycare and preschool programs. The debate in Canada is often between the effectiveness of child tax benefits and family allowance payments vs. the provision of subsidized early childhood care. Sociologists might be interested in studying whether the benefits of the Swedish system — in terms of children’s well-being, lower family poverty, and gender equality — outweigh the drawbacks of higher Swedish tax rates.

What is love (for a sociologist)?

Throughout most of history, erotic love or romantic love was not considered a suitable basis for marriage. Marriages were typically arranged by families through negotiations designed to increase wealth, property or prestige, establish ties, or gain political advantages. In modern individualistic societies on the other hand, romantic love is seen as the essential basis for marriage. In response to the question, “If a man (woman) had all the other qualities you desired, would you marry this person if you were not in love with him (her)?” only 4 per cent of Americans and Brazilians, 5 per cent of Australians, 6 per cent of Hong Kong residents, and 7 per cent of British residents said they would — compared to 49% of Indians and 50% of Pakistanis (Levine, Sato, Hashimoto, and Verma, 1995). Despite the emphasis on romantic love, it is also recognized to be an unstable basis for long-term relationships as the feelings associated with it are transitory.

What exactly is romantic love? Neuroscience describes it as one of the central brain systems that have evolved to ensure mating, reproduction, and the perpetuation of the species (Fisher, 1992). Alongside the instinctual drive for sexual satisfaction, (which is relatively indiscriminate in its choice of object), and companionate love, (the long term attachment to another which enables mates to remain together at least long enough to raise a child through infancy), romantic love is the intense attraction to a particular person that focuses “mating energy” on a single person at a single time. It manifests as a seemingly involuntary, passionate longing for another person in which individuals experience obsessiveness, craving, loss of appetite, possessiveness, anxiety, and compulsive, intrusive thoughts. In studies comparing functional MRI brain scans of maternal attachment to children and romantic attachment to a loved one, both types of attachment activate oxytocin and vasopressin receptors in regions in the brain’s reward system while suppressing regions associated with negative emotions and critical judgement of others (Bartels and Zeki, 2004; Acevedo, Aron, Fisher and Brown, 2012). In this respect, romantic love shares many physiological features in common with addiction and addictive behaviours.

In a historical context, romantic love is a product of what Williams (1977) calls a structure of feeling (see Chapter 6. Social Interaction). Narratives of chivalrous, romantic love became prominent in Europe in 12th century court poetry. They gradually became popularized as a general, societal way of feeling or experiencing love relationships. Islamic, Indian and East Asian cultures had similar literatures, but in the early romances of the story of Lancelot and Guenevere (of King Arthur fame) for example, love became codified in a specific romantic complex. This continues to inform Western popular culture and popular experience today. In the poetic narrative, spontaneous love, or love “at first sight,” is transformed into a spiritual quest in which the lovers struggle to reconcile sexual desire and moral virtue. The female object of desire is put on a pedestal, while the idolizing lover humbles himself to prove himself worthy of her through his deeds and devotion. At a time of gender inequality, arranged marriages and restrictive rituals of courtship, the poetic narrative appeared to free the expression of love from social conventions and obligations. It was “a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and self-disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent” (Newman, 1969). Giddens (1992) therefore distinguishes between passionate love, which refers to the giddy feelings of impulsive and pervasive sexual attraction or obsession with another, and romantic love which is a more historically and culturally specific structure of feeling.

In a sociological context, the physiological manifestations of romantic love are associated with a number of social factors. Love itself might be described as the general force of attraction that draws people together; a principle agency that enables society to exist. As Freud defined it, love in the form of eros, was the force that strove to “form living substance into ever greater unities, so that life may be prolonged and brought to higher development” (Freud cited in Marcuse, 1955). In this sense, as Erich Fromm put it, “[l]ove is not primarily a relationship to a specific person; it is an attitude, an orientation of character which determines the relatedness of a person to the world as a whole, not toward one ‘object’ of love” (Fromm, 1956). Fromm argues therefore that love can take many forms: brotherly love, the sense of care for another human; motherly love, the unconditional love of a mother for a child; erotic love, the desire for complete fusion with another person; self-love, the ability to affirm and accept oneself; and love of God, a sense of universal belonging or union with a higher or sacred order.

Only when the object of love is individualized in another, does it come to form the basis of erotic or intimate relationships. In this sense, romantic love can be defined as the desire for emotional union with another person (Fisher, 1992). In Robert Sternberg’s (1986) triangular theory of love, romantic love consists of three components: passion or erotic attraction (limerance); intimacy or feelings of bonding, sharing, closeness, and connectedness; and commitment or deliberate choice to enter into and remain in a relationship. The three components vary independently in long term relationships: passion starts off at high levels but drops off as the partner no longer has the same arousal value, intimacy decreases gradually as the relationship becomes more predictable, while commitment increases gradually at first, then more rapidly as the relationship intensifies, and eventually levels off. This suggests that for couples who remain together, romantic love eventually develops into companionate love characterized by deep friendship, comfortable companionship, and shared interests, but not necessarily intense attraction or sexual desire.

Although romantic love is often characterized as an involuntary force that sweeps people away, mate selection nevertheless involves an implicit or explicit cost/benefit analysis that affects who falls in love with whom. In particular, people tend to select mates of a similar social status from within their own social group. The selection process is influenced by three sociological variables (Kalmijn, 1998). Firstly, potential mates assess each others’ socioeconomic resources, like income potential or family wealth, and cultural resources, like education, taste, worldview, and values, to maximize the value or rewards the relationship will bring to them. Secondly, third parties like family, church, or community members tend to intervene to prevent people from choosing partners from outside their community or social group because this threatens group cohesion and homogeneity. Thirdly, demographic variables that effect “local marriage markets” — typically places like schools, workplaces, bars, clubs, and neighborhoods where potential mates can meet — will also affect mate choice. Due to probability, people from large or concentrated social groups have more chance to choose a partner from within their group than do people from smaller or more dispersed groups. Other demographic or social factors like war or economic conditions also affect the ratio of males to females or the distribution of ages in a community, which in turn affects the likelihood of finding a mate inside of one’s social group. Mate selection is therefore not as random as the story of Cupid’s arrow suggests.

Stages of Family Life

The concept of family has changed greatly in recent decades. Historically, it was often thought that most (certainly many) families evolved through a series of predictable stages. Developmental or “stage” theories played a prominent role in family sociology (Strong and DeVault, 1992). Today, however, these models have been criticized for their linear and conventional assumptions as well as for their failure to capture the diversity of family forms. What are the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches to family life?

The set of predictable steps and patterns families experience over time is referred to as the family life cycle. One of the first designs of the family life cycle was developed by Paul Glick in 1955. In Glick’s original design, he asserted that most people will grow up, establish families, rear and launch their children, experience an “empty nest” period, and come to the end of their lives. This cycle will then continue with each subsequent generation (Glick, 1989). Glick’s colleague, Evelyn Duvall, elaborated on the family life cycle by developing a chronology of these classic stages of family (Strong and DeVault, 1992):

| Stage | Family Type | Children |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marriage Family | Childless |

| 2 | Procreation Family | Children ages 0 to 2.5 |

| 3 | Preschooler Family | Children ages 2.5 to 6 |

| 4 | School-age Family | Children ages 6–13 |

| 5 | Teenage Family | Children ages 13–20 |

| 6 | Launching Family | Children begin to leave home |

| 7 | Empty Nest Family | “Empty nest”; adult children have left home |

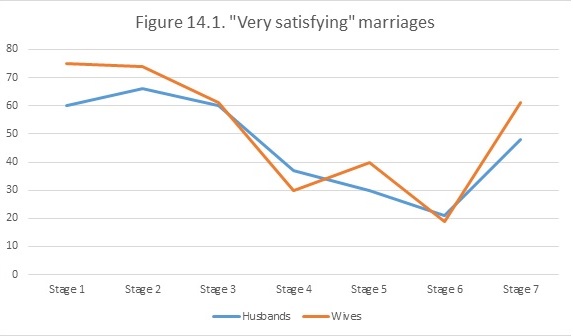

The family life cycle was used to explain the different processes that occur in families over time. Sociologists view each stage as having its own structure with different challenges, achievements, and accomplishments that transition the family from one stage to the next. The problems and challenges that a family experiences in Stage 1 as a married couple with no children are likely very different than those experienced in Stage 5 as a married couple with teenagers. Marital satisfaction of husbands and wives, for example, tends to be high at the beginning of the marriage and remain so into the procreation stage (children ages 0-2.5), falls as children age and reaches its lowest point when the children are teenagers, and then increases again when the children reach adulthood and leave home (Lupri and Frideres, 1981). The most maritally satisfied couples are those who do not have children and those whose children have left home (“empty nesters”), which is ironic considering people often get married to have children (Murphy and Staples, 1979). Some interpret this pattern as meaning simply that between couples “illusions disappear and disenchantment ensues,” whereas the developmental approach of family stages suggests “that meanings couples attached to their relationship and their roles change over time and thus affect marital satisfaction” (Lupri and Frideres, 1981). The success of a family can be measured by how well they adapt to these challenges and transition into each stage.

These early “stage” theories have been criticized for generalizing family life and not accounting for differences in gender, ethnicity, culture, and lifestyle. Less rigid models of the family life cycle have been developed in an effort to be more inclusive. One example is the family life course, which recognizes the sequence of events that occur in the lives of families but views them as parting terms of a fluid course rather than in consecutive stages (Strong and DeVault, 1992). Family relationships and significant events are negotiated, interpreted and responded to in an open-ended manner. This type of model accounts for changes in family development, such as the fact that today, childbearing does not always occur with marriage. It also sheds light on other shifts in the way family life is practiced. Society’s modern understanding of family renders rigid “stage” theories questionable and is more accepting of new, fluid models.

In fact contemporary family life has not escaped the phenomenon that Zygmunt Bauman calls fluid (or liquid) modernity, a condition of continuous mobility and change in relationships (Bauman, 2000). In earlier periods of modernity, the stages and life course of the family were fixed by institutional structures, norms, as well as ritualized events like stag parties and baby showers, reinforced by the stability of work and career, schooling, extended family and face-to-face relationships in local neighbourhoods. In late modernity, families are far more open, flexible and fragile. They depend on enduring voluntary commitments (Giddens, 1991). In this context, one stage of family life does not neatly transition into the next. The course of family life unfolds in a series of “open experience thresholds,” which can develop in a number of directions. Researching the family life of Silicon Valley in the 1980s, Judith Stacey (1990) noted that the families in her study were often innovative and created new social forms of family relation in response to the uncertainty involved in family crises and transitions. Divorce extended families for example, emerge as a result of family breakdown in which new partners, ex-spouses, biological and stepchildren, friends, relatives, stepparents and ex in-laws are mobilized as a network of resources to draw from to manage precarious family life.

The Global, Macro, Meso and Micro Family

The family is an excellent example of an institution that can be examined at the micro, meso, macro and global levels of analysis.

At the global level, a key concern around families since the 1960s has been around family size and population growth. Population growth in mainly poor 3rd World countries has been presented as a global problem that threatens the carrying capacity of the planet. There is a debate here however. Firstly, industrialized countries with small families and only 25% of the world’s population, are responsible for 50–90% of commodity consumption (Parikh and Painuly, 1994). Secondly, the causes of large family size in the 3rd World are poorly understood. High birth rates are often presented as the outcome of ignorance and irrational decision making, but in impoverished areas large families often make sense because they provide labour and social security for families (Hartmann, 2016). Thirdly, because of this poor understanding, one product of “population explosion” anxiety has been coercive, target driven population reduction programs like China’s one-child policy and India’s sterilization policy. In the 1990s, the Peruvian government sterilized 300,000 indigenous women without their consent. These policies have had tragic consequences.

Hartmann (2016) argues instead that the key global variable affecting overpopulation is the economic subordination of women. It both increases women’s need for children and impedes their ability to practice birth control. Hartmann argues that a more effective population control strategy would be based on reproductive justice: promoting women’s bodily integrity, health, and reproductive self-determination around the world. The reality is that “most countries have undergone a demographic transition to smaller families. Better living standards, improved access to education, health care, and social security, declines in infant and child mortality, rising costs of raising children, and improvements in women’s status, including employment opportunities outside the home, all have encouraged smaller family size” (Hartmann, 2016). These are global level variables and patterns affecting family size on a global scale.

At the macro-level, functionalist and critical sociologists debate the rise of non-nuclear family forms as a phenomenon within societies. Macro-level analyses focus on the family in relationship to individual societies. Since the 1950s, the functionalist approach to the family has emphasized the importance of the nuclear family — a cohabiting man and woman who are married and have at least one biological child under the age of 18 — as the basic unit of an orderly and functional society. Although only 39% of families conformed to this model in 2006, in functionalist approaches, it often operates as a model of the normal family, with the implication that non-normal family forms lead to a variety of society-wide dysfunctions such as crime, drug use, poverty, and welfare dependency.

On the other hand, critical perspectives emphasize that family form responds to historical changes and struggles within the economic, political and legal structures of society. The contemporary diversity of family forms does not indicate the “decline of the family” (i.e., of the ideal of the nuclear family) but the diverse responses of the family form to the tensions of gender inequality and historical changes in the economy and society. The typically large, extended family of the rural, agriculture-based economy 100 years ago in Canada was very different from the single breadwinner-led “nuclear” family of the Fordist economy following World War II. It is different again from today’s families who have to respond to economic conditions of precarious employment, the need for dual incomes, and changing norms of gender and sexual equality. In the critical perspective, the nuclear family should be thought of less as a normative model for how families should be and more as an historical anomaly that reflected the specific social and economic conditions of the two decades following the Second World War. These are analyses that set out to understand the family within the context of macro-level processes or society as a whole.

At the meso-level, the sociology of mate selection and marital satisfaction reveal the various ways in which the dynamics of inter-group relations, or the family form itself, act upon the desire, preferences, and choices of individual actors. At the meso-level, sociologists are concerned with interactions at the local level where multiple social roles and statuses interact simultaneously (e.g., family role, ethnicity, education, church, etc.). Since the spontaneity of romantic love and notions of individual “chemistry” have become so central to our concepts of mate selection in Western societies, it is interesting to note the social and group influences that impinge on what otherwise seems a purely individual choice: the appraisal of socially defined “assets” in potential mates, in-group/out-group dynamics in mate preference, and demographic variables that affect the availability of desirable mates (see discussion below).

Similarly, it is possible to speak of the life cycle of marriages independently of the specific individuals involved. This area of study is another meso-level analysis. Marital dissatisfaction and divorce peak in the 5th year of marriage and again between the 15th and 20th years of marriage. The presence or absence of children in the home also affects marital satisfaction — non-parents and parents whose children have left home have the highest level of marital satisfaction. Thus, the family form itself appears to have built-in qualities or dynamics regardless of the personalities, specific qualities, or micro-level interactions of family members.

At the micro-level of analysis, sociologists focus on the dynamics between individuals within families. One example, of which probably every married couple is acutely aware, is the interactive dynamic described by exchange theory. Exchange theory proposes that all relationships are based on giving and returning valued “goods” or “services.” Individuals seek to maximize their rewards in their exchanges with others. How do they weigh up who is contributing more, and who is contributing less, of the valuable resources that sustain the marriage relationship (such as money, time, chores, emotional support, romantic gestures, quality time, etc.)? What happens to the family dynamic when one spouse is a net debtor and another a net creditor in the exchange relationship?

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, the Czech novelist Milan Kundera describes the way every relationship forges an implicit contract regarding these exchanges within the first 6 weeks. It is as if a template has been established that will govern the nature of the conflicts, tensions, and disagreements between a married couple for the duration of their relationship. Kundera is writing fiction, but the dynamic he describes exemplifies a micro-level analysis in that this “contract” is a form created through the interaction between specific individuals. Afterwards, it acts as a structure that constrains their interaction. In the more severe cases of unequal exchange, domestic violence, whether physical or emotional, can be the result. The dynamics of “intimate terrorism” and “violent resistance” describe the extreme outcomes of unequal exchange.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The Evolution of Television Families

Whether one grew up watching the Cleavers, the Waltons, the Huxtables, the Simpsons, or the Roses, most of the iconic families seen in television sitcoms included a father, a mother, and children cavorting under the same roof while comedy ensued. The 1960s was the height of the suburban American nuclear family on television with shows such as The Donna Reed Show and Father Knows Best. While some shows of this era portrayed single parents (My Three Sons and Bonanza, for instance), the single status almost always resulted from being widowed, not divorced or unwed.

Although family dynamics in real North American homes were changing, the expectations for families portrayed on television were not. North America’s first reality show, An American Family (which aired on PBS in 1973) chronicled Bill and Pat Loud and their children as a “typical” American family. Cameras documented the typical coming and going of daily family life in true cinéma-vérité style. During the series, the oldest son, Lance, announced to the family that he was gay, and at the series’ conclusion, Bill and Pat decided to divorce. Although the Loud’s union was among the 30% of marriages that ended in divorce in 1973, the family was featured on the cover of the March 12 issue of Newsweek with the title “The Broken Family” (Ruoff, 2002).

Less traditional family structures in sitcoms gained popularity in the 1980s with shows such as Diff’rent Strokes (a widowed man with two adopted African American sons) and One Day at a Time (a divorced woman with two teenage daughters). Still, traditional families such as those in Family Ties and The Cosby Show dominated the ratings. The late 1980s and the 1990s saw the introduction of the dysfunctional family. Shows such as Roseanne, Married with Children, and The Simpsons portrayed traditional nuclear families, but in a much less flattering light than those from the 1960s did (Museum of Broadcast Communications, 2011).

Over the past 10 years, the nontraditional family has become somewhat of a tradition in television. While most situation comedies focus on single men and women without children, those that do portray families often stray from the classic structure: they include unmarried and divorced parents, adopted children, gay couples, and multigenerational households. Even those that do feature traditional family structures may show less traditional characters in supporting roles, such as the brothers in the highly rated shows Everybody Loves Raymond and Two and Half Men. Even wildly popular children’s programs as Disney’s Hannah Montana and The Suite Life of Zack & Cody feature single parents.

In 2009, ABC premiered an intensely nontraditional family with the broadcast of Modern Family. The show follows an extended family that includes a divorced and remarried father with one stepchild, and his biological adult children — one of who is in a traditional two-parent household, and the other who is a gay man in a committed relationship raising an adopted daughter. While this dynamic may be more complicated than the typical “modern” family, its elements may resonate with many of today’s viewers. “The families on the shows aren’t as idealistic, but they remain relatable,” states television critic Maureen Ryan. “The most successful shows, comedies especially, have families that you can look at and see parts of your family in them” (Respers France, 2010).

Image Descriptions

Figure 14.12 long description:

| Number of men who rate their marriage as “very satisfying” (%) | Number of women who rate their marriage as “very satisfying” (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Childless | 60 | 75 |

| Stage 2: Children 0 to 2.5 | 66 | 84 |

| Stage 3: Children 2.5 to 6 | 60 | 61 |

| Stage 4: Children 6 to 13 | 37 | 30 |

| Stage 5: Children 13 to 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Stage 6: Children begin to leave home | 21 | 20 |

| Stage 7: “Empty Nest” | 49 | 61 [Return to Figure 14.12] |

Media Attributions

- Figure 14.3 Free styling by Yusaini Usulludin, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.

- Figure 14.4 Léon Gérin (1863-1951), circa 1920 by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, reference number: P1000, S4, D83, PG28, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 14.5 File:087.King Solomon in Old Age.jpg, by Gustave Doré (1832–1883), in Doré’s English Bible, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 14.6 Blackfoot man and his two wives [ca. 1876-1879] from the Glenbow Archives. [This image is now in the Blackfoot Digital Library, ID: 37154_10150319796380578_4910152_n, and is in the public domain.

- Figure 14.7 Cousin explainer, by Lane Genealogy, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 14.8 A Mosuo girl in bridesmaid costume by Rod Waddington is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

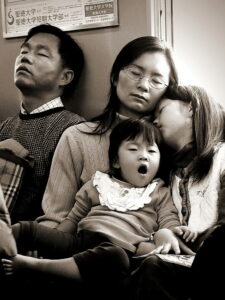

- Figure 14.9 Let’s go home by Thanh Mai Bui Duy, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.

- Figure 14.10 Psyche & Cupid by Riccardo Cuppini, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 14.11 All Romances 2, credited to Alice Kirkpatrick at Ace Magazine, via Comic Book+, is in the public domain.

- Figure 14.12 Data from Figure 4 in The quality of marriage and the passage of time: Marital satisfaction over the family life cycle, The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, 6(3), 283–305 (Lupri and Frideres, 1981). [Original graph from Introduction to Sociology, OpenStax College] Used under a CC BY 3.0 licence.

- Figure 14.13 Families, by bass_nroll, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 14.14 File:The Loud Family 1973.JPG from the PBS-Public Broadcasting System, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.