Chapter 16. Media and Popular Culture

16.2 Sociological Frameworks for Understanding Media

William Little and Ron McGivern

The theme of how different sociological paradigms or perspectives frame research into the specific topics of sociology has been developed throughout this textbook. Studying the effects of media and the nature of mediated society is no different. Positivist approaches tend to formulate the research in terms of cause-and-effect relationships between measurable variables. These causal relationships can also be modelled on the different social functions that media perform in supporting and perpetuating the processes of society. Critical sociological approaches focus on the influence of power structures on media, particularly the ideological messaging of media gatekeepers, the circulation of damaging stereotypes in the media, and the effects of turning communications into commodities. The interpretive approaches emphasize the ongoing processes in which meanings are actively constructed in the media and then actively deciphered by audiences.

Positivism and Functionalism

Media Effects

A glance through popular video game, television and movie titles geared toward children and teens shows the vast spectrum of violence that is displayed, condoned, and acted out. It may hearken back to Popeye and Bluto beating up on each other, or Bugs Bunny getting the better of Elmer Fudd, but the graphics and actions have moved far beyond the Loony Tunes brand of slapstick violence.

When 20-year-old Adam Lanza shot more than two dozen students and staff members of Sandy Hook Elementary School as well as his own mother in 2012, an old debate about the influence that violent video games has on young people was reignited. The free online game, Kindergarten Killers, a game Lanza played, was blamed: playing violent games makes people violent. But others argue that it is people with violent tendencies that are drawn to violent games. The question remains: are violent video games the cause of violent behaviour or are they merely the manifestation of violent tendencies?

This is essentially the same debate people have about media effects in general. Historically, it has been regarded as intuitive that media has a tremendous effect on audiences, not only in the case of violent media, but also with respect to political propaganda, advertising, moral panics, pornography, racial stereotyping, and other influential media content. The positivist model of explanation is drawn from behaviouralism — a linear sequence of sender/message/receiver in which the message is a stimulus and the reception is a measurable response in the audience: effects, uses, gratifications, behaviours, etc.

For example, George Gerbner proposed a cultivation model of violent media effects: the more people watch television and are exposed to its violent content, the more likely they will be to perceive their society or the world around them as being more violent than it really is (Gosselin et al., 1997). Violent television cultivates a perception of the world as violent. Research has shown that establishing causation is not as easy as it seems, however.

Children’s play has often involved games of aggression — from cops [police] and robbers, to water-balloon fights at birthday parties, to acts of social aggression (social exclusion, public humiliation, and personal rejection). Where does this aggression come from and how do media influence it?

Gosselin et al. (1997) studied Canadian television in the 1990s and found that children’s programs were more violent than adult programs. They contained four times more violent scenes per hour, and 76.9% of these programs contained violence compared to only 58.9% for adult programs. Moreover, the violence shown to children originated almost exclusively from cartoons. Of these, 79.5% contained violence, averaging 24.8 violent scenes per hour. In addition, 57.7% of the main cartoon characters were violent.

The media effects approach links violent media and violent behaviour. Reviewing three major American studies spanning 3o years, Alter (1997) reports that violence on television has been associated with three different types of effect: viewers exhibiting increased aggression or violence toward others (the aggressor effect); increased fearfulness about becoming a victim of violence (the victim effect); and increased insensitivity about violence among others (the bystander effect).

Similarly, psychologists Anderson and Bushman (2001) reviewed 40+ years of research on children’s violent video game use and aggression. They found that children who had just played a violent video game demonstrated an immediate increase in hostile or aggressive thoughts, an increase in aggressive emotions, and physiological arousal that increased the chances of acting out aggressive behaviour (Anderson, 2003). They found that repeated exposure to this kind of violence leads to increased expectations regarding violence as a solution, increased violent behavioural scripts, and making violent behaviour more cognitively accessible (Anderson, 2003). In short, people who play these games find it easier to imagine and access violent solutions than nonviolent ones, and are less socialized to see violence as a negative.

However, subsequent re-evaluations of this literature have shown that the correlations are weak, non-existent, or sometimes contradictory. Gosselin et al.’s (1997) study of university students self-reporting on the effects of watching violent television showed television viewing did not have any influence on the emotion people feel about the surrounding world (i.e., fear), but did affect their cognitive beliefs about the level of violence in society. A recent meta-analysis of the literature on violent video games and aggression showed negligible relationships between violent games and aggressive behavior, small relationships with aggressive emotions and cognitive beliefs, and stronger relationships with desensitization to violence (Ferguson et al. 2020). Similarly, the American Psychological Association has acknowledged that violent video games strongly correlate with aggressive behavior, as well as anti-social behavior, but distinguishes between aggression and violence. They conclude that there is little evidence for a causal or correlational connection between playing violent video games and actually committing criminal violence, but that violent game use is a risk factor for violence (APA Task Force on Violent Media, 2015).

Establishing causation is extremely difficulty in media research due to the multiple factors that are present. Most media research relies on content analysis and surveys where the subjects are asked to self-report. This has been criticized as unreliable, and at best can only establish a correlation. To demonstrate causation, all other factors must be controlled. Usually this can only take place under laboratory conditions and not in a real-life context where factors are complex and unpredictable.

Media Functions

Structural functionalism focuses on how media performs key social functions that contribute to smooth operation of society. A good place for students to begin to understand this perspective is to write a list of functions they perceive media to perform for them. The list might include the ability to find information on the internet, the entertainment provided by going to movies, or how advertising algorithms uncannily guess what products they are searching for. Students might also think about the latent functions media perform by communicating social norms of fitness, attractiveness, heroism, and knowledgeability. These latent functions often take the form of creating a common collective consciousness in which, like it or not, people come to share a common perception of attractive body types, racial stereotypes, desirable status symbols, moral vs. immoral behaviour, etc.

Social Solidarity Function

Emile Durkheim argued that “essentially social life is made up of representations,” however “these collective representations are of quite another character from those of the individual” (Durkheim, 1952/1897). The collective representations that are shared and circulate through the media — media stories, images, narratives, musical expressions, celebrity characters, film clips, etc — are part of a collective conscience, “the totality of beliefs and sentiments common to average citizens of the same society” (Durkheim, 1937/1895). Like other social facts he describes (see Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology), the collective conscience “forms a determinate system which has its own life,” independent of the private thoughts and mental images of individuals (Durkheim, 1937/1895).

The contemporary media function to create this shared space of collective representations of the world — all “the ways in which the group conceives of itself in relation to objects which affect it” (Durkheim, 1937/1895). One element that made the collective conscience distinct from the isolated minds of individuals was its “unusual intensity.” “Sentiments created and developed in the group have a greater energy than purely individual sentiments” (Durkheim, 1985). This is evident to anyone who has attended a lively hockey game, a large wedding, or a spiritual ceremony. Whatever any individual feels about these events, the feelings are inevitably amplified by sharing them with others. Similarly, it is one thing to suspect shady goings-on and secret conspiracies and another to discover a corner of the internet where many people share these beliefs and have one’s beliefs affirmed.

This is the source of the function of the collective conscience in social life: to overcome the tendency towards individual isolation and dispersion in society and create social solidarity. Collective representations are a means of binding individuals together in coordinated action and perception through the power of shared ideas, beliefs, and feelings. “[F]ollowing the collectivity, the individual forgets himself [sic] for the common end and his conduct is directed by reference to a standard outside himself” (Durkheim, 1985). When an element of collective conscience determines an individual’s conduct, “we do not act in our personal interest; we pursue collective ends” (Durkheim, 1985). The media creates a collective conscience that functions to integrate individuals into societal goals.

Durkheim was writing in the late 19th and early 20th century when newspapers and other print forms were the dominant media, so his tendency was to examine their function in creating social solidarity at a national or societal level. Today the role of new media forms in reaching and penetrating the consciousness of individuals seems even more powerful and widespread. The new media create a common, thoroughly mediated, experience of the world that is global in scope. Arjun Appadurai (1996) describes the formation of a global mediascape. Like a landscape, the mediated environment of the global citizen creates a common stock of media images, celebrities and news events that circulate around the world through digital and other media.

Mediascapes, whether produced by private or state interests, tend to be image-centered, narrative-based accounts of strips of reality, and what they offer to those who experience and transform them is a series of elements (such as characters, plots, and textual forms) out of which scripts can be formed of imagined lives, their own as well as those of others living in other places (Appadurai, 1996).

Mediascapes are also like landscapes in the sense that they look different depending on where someone is situated, but are nevertheless composed of the same fields, hills, and sky. In this analogy, mediascapes are the common, imagined worlds created by the global circulation of images in the media. However, the function of creating social solidarity through collective representations can be thoroughly ambiguous. It is through these shared imaginings of the other and of the shared global condition, that people in distant parts of the planet can band together to recognize the dignity of universal human rights or the existential threat of climate change, but they also circulate false or inflammatory information that leads to burning Korans in Denmark and fierce global counter-protests.

Social Coordination Function

As discussed earlier in the chapter, mediated forms of communication function to coordinate the activities of society, especially when they get too large or complex for face-to-face communication to be effective. Harold Innis (1951) separated the militaristic societies that sought to control vast areas of space from the religious societies that sought to control vast periods of time by how their dominant forms of communication functioned. Light and ephemeral paper media were suited to distributing administrative messages over space, while durable and permanent stone or clay media were suited to supporting the transmission of eternal values and connection to the ancestors through time. The mass media of the 19th and 20th centuries were key to creating the public spheres and common sources of information needed for the formation of democracy and national societies. In a huge, regionally distinct and disperse country like Canada, the mass media functioned as key institutions in creating a common sense of Canadian citizenship. In similar fashion, Castells (2010 [1996]) described the way that new digital technologies of media functioned to enable contemporary networked forms of global coordination to function.

Another example of the social coordination function of media is advertising. Companies that wish to connect with consumers find television and digital media irresistible platforms to promote their goods and services. Television and internet advertising are highly functional ways to meet a market demographic where it lives and thus coordinate circuit of commodity production, distribution, sale, and consumption more effectively and efficiently. In the era of television, sponsors used the sophisticated data gathered by network and cable television companies about their viewers to target their advertising accordingly. They used advertising to sell to audiences. Today the way they reach consumers is changing. It might be more accurate to say that the big social media platforms not only sell to audiences, but sell audiences themselves, i.e., their demographic information, likes, preferences, browsing history, searches, on-line shopping habits, etc. The trend towards niche marketing to small but valuable consumer groups becomes ever more customized as consumer preferences and decisions become more accurately modeled and predictable based on the vast amounts of data accumulated by social media platforms. Consumers know that they are thoroughly integrated into the cycle of commodity production when the advertising algorithms know what they want before they do themselves.

Entertainment Function

An obvious manifest function of media is its entertainment value. Most people, when asked why they watch television, go to the movies or stream YouTube clips, would answer that they enjoy it. Media function to give people pleasure, to allow them to relax, or to provide means of escape from the grind and obligations of everyday life. In their entertainment function, media provide forms of popular culture that do not require much effort to access, consume or digest. One YouTube clip leads to another and pretty soon a couple hours have gone by. In this form, their function is not practical — in the sense of building useful work skills or academic knowledge — nor is it self-cultivating and self-expressing, but it may provide stress relief.

The easily digestible format of most media entertainment allows people to release tension and replenish their energy to return to the challenging tasks of work, family life, relationships with others and so on. This can enable people to find balance in their lives, but as noted earlier in the chapter, critics of the culture industry point to the passive, uncritical attitude of “distraction and inattention” in which most media entertainment is consumed (Adorno, 1991/1941). This does not lead to a sustainable enjoyment of life, let alone critical examination of the reasons for stressful and unsatisfying work or family conditions. Instead, it leads people to simply adjust psychically and submit to the world as it is.

On the media technology side, as well, there is some ambiguity to the entertainment factor of the use of new innovations. From online gaming to chatting with friends on Facebook, technology offers new and more exciting ways for people to entertain themselves. Of course, the downside to this ongoing information flow is the near impossibility of disconnecting from technology, leading to an expectation of constant convenient access to information and people. Such a fast-paced dynamic is not always to people’s benefit. Some sociologists assert that this level of media exposure leads to narcotizing dysfunction, a term that describes when people are too overwhelmed with media input to really care about the issue, so their involvement becomes defined by awareness instead of by action about the issue at hand (Lazerfeld and Merton, 1948).

Socialization Function

Even while the media is often seen as a means of escape, it also serves to socialize people, functioning to enable societies to pass along norms, values, and beliefs to the next generation. In fact, people are socialized and resocialized by media throughout their life course. All forms of media teach people what is good and desirable, how they should speak, how they should behave, and how they should react to events. The division of fictional or non-fictional characters into heroes and villains for example conveys powerful messages about what is morally admirable or despicable in a society. Media also provide people with cultural touchstones during events of national or global significance. They announce what is important or historical for societies. How many older relatives still recall watching the first landing of astronauts on the moon on the first colour televisions, or the 1972 Canada-USSR Summit Series? How many of them saw the events of September 11, 2001, unfold on television? How many readers of this textbook saw the Russian invasion of Ukraine on television or clips on the internet?

Where the family remains a key institution of socialization, family members often spend more time with media than with each other. In 2021, Canadians 18 years and older spent an average of five hours and 26 minutes with digital media each day and four hours and 48 minutes with traditional media (TV, magazines, newspapers, and radio) (Guttman, 2023). Children between 2 years and 11 years watched 10.5 hours of TV a week and teenagers watched 10 hours (Stoll, 2022). While teenagers only accounted for 2.5% of all social media users in Canada in 2021 (Dixon, 2022), a Statistics Canada survey from 2018 showed that 92% of teenagers were regular internet users (Schimmele et al., 2021).

It is clear from watching people emulate the styles of dress and talk that appear in media that media has a socializing influence. Sometimes this has a positive effect in expanding people’s horizons. Other media influences, like social media “challenges” to eat packages of detergent or to drink enough Benadryl to become delirious, seem more dubious. Digital media in particular is especially engrossing and influential on identity formation. Twenge, Spitzberg and Campbell (2019) observe that adolescents in the “iGeneration” (those born in the 1990s) are spending less time on in-person social activities than previous generations of adolescents — a change that parallels the increases in time spent on digital media. This raises questions about whether these new media of communication are functional or dysfunctional as agents of socialization. According to the authors, feelings of loneliness are comparatively higher among adolescents in the iGeneration. The highest levels of loneliness are found among youth with low amounts of in-person social contact and high amounts of social media use.

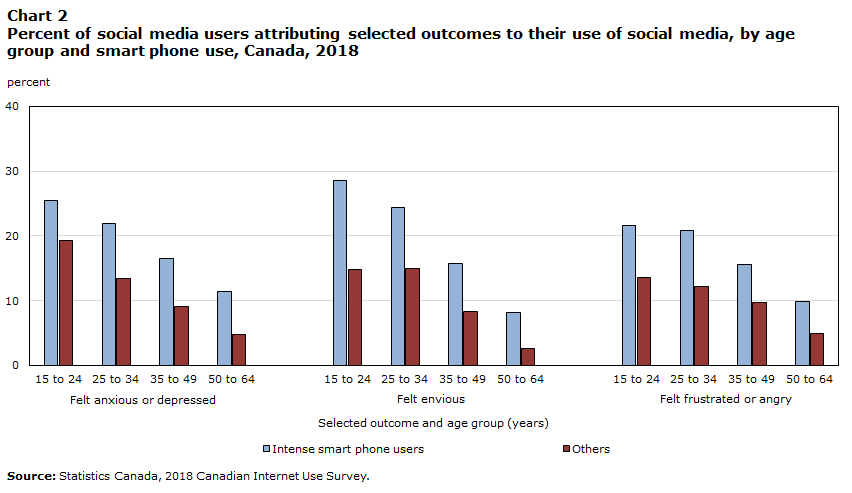

The findings of Statistics Canada’s 2018 Canadian Internet Use Survey also show that intense smart phone use was associated with anxiety/depression, feelings of envy, and frustration/anger (see Figure 16.13 below). This casts doubt about the extent to which online social relationships are a source of companionship, emotional sustenance, and social support that contribute to mental health and wellbeing, particularly in the absence of face-to-face interactions (Helliwell and Huang 2013). In other words, it raises questions about ability of smart phones and digital media to socialize teenagers and young adults effectively.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Socialization and Social Media: Risk Factors

Schimmele et al. (2021) summarize the literature on the positive and negative outcomes associated with social media use, and their associated risk factors:

Age has been viewed as a risk factor for a number of reasons. A comparative lack of self-regulation among children and adolescents may impede their ability to avoid risks such as overuse of social media or use at inappropriate hours (Keles, McRae and Grealish, 2020). Both sleep duration and sleep quality have been linked to daily time spent on social media and nighttime use, which tend to be higher among adolescents and young adults than among older individuals (Reid Chassiakos et al., 2016; Woods and Scott, 2016). In general, lost sleep has been found to contribute to daytime dysfunction, such as having trouble concentrating (Reid Chassiakos et al., 2016). Furthermore, disrupted sleep has been found to be a key link between the quantity of time that youth spend on social media and depressive symptoms (Kelly et al., 2018; Reid Chassiakos et al., 2016). Disrupted sleep may also be an outcome of poor-quality interactions on social media such as exposure to online harassment or bullying, which are also negatively correlated with mental wellbeing (Kelly et al., 2018; Pew Research Center, 2018).

The age of social media users also matters as a risk factor for negative outcomes given developmental processes underway through adolescence. Identity formation is one such process and involves social comparison and feedback-seeking (Nesi and Prinstein, 2015). Social media is a unique interpersonal environment in this context as it can provide a near-continuous flow of interactions and an immense basis for social comparison and feedback (Vogel et al., 2014). Evidence suggests that social media has increased the influence of peer groups on the wellbeing of adolescents, facilitating and magnifying the effects of self-comparison at this age (Kelly et al., 2018; Seabrook, Kern and Rickard, 2016). In addition, users on social media platforms may strive for “positive self-presentation” using flattering images and information about exciting activities, material success and personal accomplishments (Tandoc, Ferruci and Duffy, 2015; Verduyn et al., 2015). For browsers, frequent exposure to, and comparison with, such representations can lead to idealized perceptions of other peoples’ lives, with increased potential for negative social comparisons and feelings of social deprivation, lower self-esteem and unhappiness (Georges, 2009; Nesi and Prinstein, 2015; Primack et al., 2017; Tandoc, Ferrucci, and Duffy, 2015;). Nesi and Prinstein (2015) report that social comparison poses a greater threat to the mental wellbeing of adolescent girls than boys, possibly because girls place more emphasis on social comparison when assessing their self-worth.

While most studies of social media impacts have focused on negative outcomes, others have documented positive outcomes. Social media is an efficient tool for interacting with friends and relatives, maintaining relationships across distance, and facilitating scheduling and communication among household members. Social networking sites connect individuals with shared interests, values, and activities, and enable individuals to interact with extended networks that would be difficult to maintain in an offline context (Boyd and Ellison, 2007; Verduyn et al., 2017). Some studies report that having a large number of online contacts predicts higher levels of life satisfaction and self-perceived social integration (Manago, Taylor and Greenfield, 2012; Seabrook, Kern and Rickard, 2016; Verduyn et al., 2017). Social networking sites can also reduce barriers to social participation (Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe, 2007). Several studies have documented correlations between social media and positive outcomes, such as emotional support and diminished social isolation and loneliness (Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe, 2007; Keles, McRae and Grealish, 2020; Oh, Ozkaya and LaRose, 2014).

Literature review by Schimmele et al. (2021), used under the Statistics Canada Open Licence.

Social Control Function

Like the functions of social solidarity, social coordination and socialization, media perform the function of producing conformity to social norms and are thereby a means of exercising social control over populations. As noted in Chapter 8. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control, all societies practice social control, the regulation and enforcement of norms. Social control can be defined broadly as an organized action intended to change or correct people’s behaviour (Innes, 2003). The underlying goal of social control is to maintain social order, the ongoing, predictable arrangement of practices and behaviours on which society’s members base their daily lives.

A prime example of this function of the media is the “true crime” show, which often sensationally reiterates and reinforces the qualities of heroic law enforcement and villainous criminality. By showing law enforcement, victims and model citizens in the best light and criminality in the worst light, this genre of media reinforces social beliefs about who deserves punishment and who deserves rewards. Similarly, true crime podcasts like Someone Knows Something that re-investigate cold cases, the lives of serial killers, child abductions, the procurement techniques of cults and so on, draw on the minutia of transgressions surrounding major crimes like murder to reinforce the need for societal vigilance. Vicary and Fraley’s (2010) research shows that women in particular are drawn to the true crime genre because of “the potential life-saving knowledge” they provide. “For example, by understanding why an individual decides to kill, a woman can learn the warning signs to watch for in a jealous lover or stranger” (Vicary and Fraley, 2010).

Media are also direct means of surveillance and social control. The panoptic surveillance envisioned by Jeremy Bentham and later analyzed by Michel Foucault (1975) is increasingly realized in the form of technology used to monitor people’s every move. This surveillance was imagined as a form of complete visibility and constant monitoring in which the observation posts are centralized and the observed are never communicated with directly. Today, digital security cameras capture people’s movements, satellite technologies track people through their cell phones, and police forces around the world use facial-recognition software.

Critical Sociology

In contrast to theories in the positivist perspective, the critical perspective focuses on the creation and reproduction of power relations and inequality through the media — social processes that tend to destabilize society and create conflict rather than contribute to its smooth operation. The focus of critique is to provide the conditions for positive change that address systematic patterns of inequality and exclusion.

A key concept of the critical approach is the critique of ideology, the presentation of a partial view of the world as objective and universal. As Karl Marx put it, “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas” (Marx and Engels, 1998/1846). The media present an image or idea of the world from the narrow point of view of the wealthy and powerful, or dominant class. For Marx this was at odds with the worldview and the interests of the working class who form the vast majority of a society’s population. “The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, consequently, also controls the means of mental production, so that the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are on the whole subject to it” (Marx and Engels, 1998/1846).

As the media, as “means of mental production” are mostly privately owned, the critical sociological focus on media concentration and corporate ownership of the media is largely a question concerning whose ideas, messages and points of view are being transmitted and whose are not. This does not mean that the media only present the world view of the ruling class. Just as the power of the ruling class is contested in society as a whole, media representations are also contested. The key point is that in sociology the term ideology does not refer simply to a set of ideas (like conservativism, liberalism, socialism, racism, environmentalism, etc.) but to a set of ideas that conceal, distort, or justify power relations in a society. Ideology critique is the practice critical sociologists use in the study of media to analyze and challenge the underlying ideological assumptions of media texts.

For example, news coverage concerning the economy often focuses on stock markets, corporate takeovers, quarterly earnings, interest rates, commodity prices and the like. Economic “growth” is a good news story, whereas economic “contraction” or “stagnation” is a bad news story. This is a picture of the economy from the point of view of large investors of capital. From their point of view, this is the way the economy works, and these are the events that interest them. In other words, it is a partial view of the economy, which is very different from the lived experience of most people who go to work, are seeking jobs, or live off a wage or salary. Moreover, from Marx’s point of view, it is a picture of the economy conceals or distorts the reality of the actual economy that most people experience because the everyday social relations of class, concerns with precarious employment and making ends meet, quality of work life, hyper exploitation and global inequality, environmental destruction, etc. are simply not part of the picture.

Critical sociologists also look at who controls the media, and how media promotes the norms of upper-middle-class white demographics while minimizing the presence of the working class, marginalized groups, and racialized minorities.

For example, a study from Gilchrist (2010) showed a large disparity in the amount and content of coverage in a sample of white and Indigenous women who were missing and suspected victims of violent crimes. Newspapers gave the Indigenous women three and a half times less coverage; their articles were shorter and were less likely to appear on the front page. The white women were often described in news reports as being “gifted” or “cherished,” while Indigenous women were describe as being “pretty” or “shy.” The amount of personal information included in accounts of the White women far outweighed the amount and depth of information presented about the Indigenous women. The overall effect, Gilchrist argues, is that “the systematic exclusion, trivialization, and marginalization of missing/murdered Aboriginal women can be described as symbolic annihilation” (Gilchrist, 2010). Whereas the white women’s lives were represented as newsworthy — “legitimate, worthy, and innocent” — Indigenous women’s victimization was represented as routine and their lives were erased. Moreover, “the lack of coverage might also create a vicious cycle, whereby inattention to Aboriginal women’s victimization by the police and community is reinforced by the lack of coverage” (Gilchrist, 2010).

This is also a problem of stereotypes used in the media to present oversimplified ideas about groups of people based on rigid generalizations. They do not bear up under close examination but are repeated often enough to become shorthand ways to characterize whole groups of people. The white women Gilchrist studied fell into well established and romanticized representations of white womanhood — purity, cleanliness, vulnerability, and virginity (Dyer, 1997) — but the Indigenous women were represented with colonial stereotypes of the “squaw” — uncivilized, dirty, lazy, degraded, easily sexually exploited and incapable of rescue (Gilchrist, 2010).

Similarly generalizing stereotypes are used to characterize young Black males in Canada: the gangsta image, which characterizes Black males as dangerous, defiant and criminal, and the entertainer image, which characterizes them as athletic or musically and theatrically talented (Manzo and Bailey, 2008). One young Black offender interviewed by Manzo and Bailey described representations of Blacks in the media:

They look like — like criminals and stuff like that. Only some, only some ’cause some Black people are talented and positive people, you know, sometimes. But sometimes they just, I don’t know, sometimes they look bad. Like I know like when you’re sitting watching TV and stuff, they make them look like people from the ghetto and stuff like that all the time. Like every Black person’s from the ghetto and stuff, and do a lot of crime and stuff like that. . . . lots of people think of Black people as thugs and robbing people and stuff, you know . . . . Like some people think that a Black person’s not normal. They just think — like how there’s a lot of crime and stuff because of movies and stuff, you know, and how Black people that are in the movies, they all live in ghettos and stuff and all do crime and stuff like that. I just think that that’s how people see us (Manzo and Bailey, 2008).

Manzo and Bailey (2008) note that, “[m]ass-cultural images of Black Canadians, it would seem, not only motivate stereotyping on the part of those who are not Black: they … also influence racial identities and related self-concepts among Black persons themselves.”

Gatekeeping and Media Ownership

Powerful individuals and social institutions have a great deal of influence over what kind of media is available for popular consumption and what messages circulate in society, a form of gatekeeping. Shoemaker and Voss (2009) define gatekeeping as the sorting process by which thousands of messages are shaped into a mass media–appropriate form and reduced to a manageable amount. In other words, the people in charge of the media decide what the public is exposed to, which, as C. Wright Mills (2000/1956) famously noted, is the heart of media’s power.

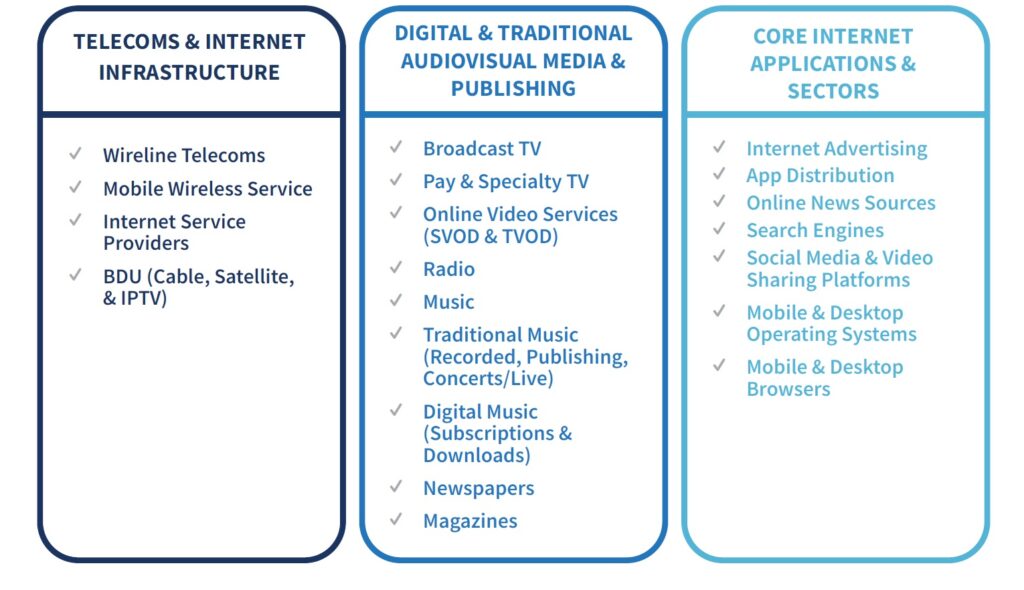

Media is also big business, and the underlying motive of the commercial media is to profit from the circulation of media content. The network media economy includes communication infrastructure companies (wired and wireless telecoms, Internet services, cable, satellite, and fibre TV), digital and traditional media (TV, radio, newspapers, and magazines) and internet application companies (online advertising, search, social platforms). This sector generated $94.6 billion in Canada in 2021, up from $89 billion in 2019 (Winseck, 2022).

Since the 1990s, corporate mergers and consolidation have lead to the concentrated ownership of the Canadian media into six multimedia companies: Bell, Telus, Rogers, Québecor, the CBC and Corus. These six Canadian companies accounted for 69% of network media economy revenue in 2021 (Winseck, 2022). When media ownership is highly concentrated like this, the concern about gatekeeper power is that a few dominant players can limit competition and control news and media content.

- Bell Media Inc. Owned by Bell Canada (BCE) and based in Montreal. Its operations include telecoms (Bell Canada, Bell Mobile), television broadcasting and production, radio broadcasting, digital media and Internet properties. Bell Media owns 35 local television stations led by CTV, Canada’s most-watched television network, and the French-language Noovo network in Québec; and 27 specialty channels, including leading specialty services TSN, MTV Canada, and Much. It owns Crave TV and the Montreal Canadians hockey team. Its revenue was reported as $23.96 billion 2019.

- Rogers Communications Inc. Owned by the Rogers family and based in Toronto. Its operations are primarily in the fields of wireless communications, cable television, and Internet services, with significant additional mass media companies. Rogers owns City TV, 13 local TV stations, sports channels (Sportsnet), network and satellite-to-cable programming and 55 radio stations across the country. It owns the Toronto Blue Jays baseball team. In 2023, it bought Shaw Communications, which had been the third largest media corporation in Canada, and was able to expand its home telecommunications services to Western Canada. Its revenue was reported as $13.9 billion in 2020, but adding Shaw Communications, which reported a revenue of $5.5 billion in 2021, will make it the second largest media conglomerate in the country.

- Telus Corp. Owned by the Bank of Montreal (as largest shareholder) and based in Vancouver. Its operations are primarily in the fields of telecommunications products and services including internet access, voice, entertainment, healthcare, video, smart home automation and IPTV (internet protocol) television. Its revenue was reported as $15.34 billion in 2020.

- Québecor. Owned by the Péladeau family and based in Montreal. Québecor Media Group has a significant hold on French Québec media and is the largest owner of French-language media in Canada. Québecor owns TVA, Le Journal de Montréal, Le Journal de Québec, 24 hrs, and Videotron. It acquired Freedom Mobile from Shaw Communications as part of the regulatory approval of the Rogers/Shaw merger. Its revenue was reported as $4.122 billion in 2017.

- CBC/Radio Canada. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) is Canada’s public broadcaster. Created by an Act of Parliament in 1936, the government-owned company provides services in both of Canada’s official languages, English and French. All told, the CBC operates two television networks, four radio networks, a cable television service, an international shortwave radio service and a commercial-free audio service. CBC operates approximately 100 radio and television stations across Canada. Its revenue was reported as $1.9 billion (including approximately $1.4 billion in government subsidy) in 2021.

- Corus Entertainment. Owned by the Shaw family and based in Toronto. Not included in the sale of Shaw Communications to Rogers, Corus Entertainment owns Global News and Global TV, which is Canada’s second most watched television network after CTV. The Television segment is comprised of 33 specialty television networks, 15 conventional television stations, digital assets, a social media digital agency, a social media creator network, technology and media services, and the Corus content business. The Radio segment includes 39 radio stations, situated primarily in urban centres in English Canada, with a concentration in the densely populated area of Southern Ontario (Institute for Quantitative Social Science, 2023). Its revenue was reported at $1.65 billion in 2018.

Also notable in terms of dominant media content producers in Canada are the PostMedia Network, owned by US private equity firm Chatham Asset Management (who also own the National Enquirer in the US), and Thomson Reuters, owned by the Thomson family who are reportedly Canada’s richest family (Institute for Quantitative Social Science, 2023). Postmedia own The National Post, The Financial Post, The Montreal Gazette, The Calgary Herald and Sun, The Vancouver Sun, The Ottawa Citizen, London Free Press, Edmonton Journal, canada.com and canoe.com, whereas Thomson Reuters own the Globe and Mail and the global news service Reuters.

One of the unique features of Canadian media ownership is its high level of vertical integration, which is when a corporation owns different businesses in the same chain of production and distribution. In Canada this means that the biggest media content producers (television, radio, newspapers, etc.) are owned by the biggest communication infrastructure corporations (wired and wireless telecoms, Internet services, cable, satellite and fibre TV). In a report on global media ownership published in 2016, Canada had the third highest level of vertical integration out of the 28 countries examined (Winseck, 2022).

Apart from the CBC, Postmedia, and Thomson Reuters, the digital and traditional audiovisual content media in Canada provide only a small percentage of overall corporate revenue, suggesting that the production of media content has largely become “ornamental” in the overall corporate strategies. This does not necessarily affect their gatekeeping role, but does emphasize that whatever media content is produced, the bottom line for the corporate media is to maximize profits. Winseck (2022) argues that content producing media “are important, but their real purpose seems to be to drive the take-up of the companies’ vastly more lucrative wireless, broadband Internet, and cable, satellite and IPTV services.” For Bell, Rogers and Québecor, 80–90% of their revenue flows from the communications infrastructure/services side of their business rather than from media content services.

Gatekeeping and Digital Media

Increasingly however, the domestic, vertically integrated media conglomerates find themselves in competition for Canadian audiences, consumers and advertising revenue with the US-based internet corporations Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Microsoft, who had 15.3% of network media economy revenue in 2021 (Winseck, 2022). Smaller players in Canada are Twitter, Snapchat and TikTok.

Some argue that media ownership concentration is therefore no longer a problem because the range of information sources and the ways people communicate have expanded significantly (Public Policy Forum, 2017). As an example, the rise in TV concentration seen between 2010 and 2014 has since reversed on account of the rise of online video services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Disney+ (Winseck, 2022). Moreover, as the new digital media evolved from the 1990s on, they displaced many traditional forms of “legacy media” (broadcast television, radio, newspapers, and magazines). The traditional mass media were centralized, one-to-many media, allowing a culturally diverse society to be dominated by one race, gender, or class. In ideological fashion, the media could impose the dominant group’s worldview as a societal norm. Digital media appear to render the gatekeeper role less of a factor in information distribution. Any citizen who has an internet connection and a computer or smart phone can produce mediated content.

On the other hand, even though digital and social media enable one-to-one, one-to-many and many-to-many forms of discourse, the economic model of the world’s most popular websites works through a mechanism similar to traditional mass media: selling the attentive capacities of audiences to advertisers. This is done in a much more targeted way however, which has implications for the new media’s gatekeeping power.

There are an estimated 2 billion websites in 2023 but they are obviously not all equal (Visual Capitalist, 2023). Using traffic rankings, Figure 16.20 shows the 50 most popular websites in 2022. The top 10 are: Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Baidu, Wikipedia, Yandex, Yahoo, and WhatsApp. Aside from Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia which is managed by the Wikimedia foundation and is a not-for-profit entity, every other site on the list is a profit making privately owned entity, most of whom generate funds through extracting user data and selling targeted advertising (Sytaffel, 2014).

The corporations which own these Websites, such as Google (Google and YouTube), Meta (Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) and XCorp (Twitter) are all multibillion dollar private companies, whose economic model is underpinned by the creation of platforms: websites or applications that enable two or more individuals or groups to interact (users, content creators, customers, advertisers, service providers, producers, suppliers, and even physical objects with 3D printing). This is the basis of platform capitalism, a business model in which value and competitive advantage are extracted from the data of platform users (Srnicek, 2017a). “By providing the infrastructure and intermediation between different groups, platforms place themselves in a position in which they can monitor and extract all the interactions between these groups. This positioning is the source of their economic and political power” (Srnicek, 2017b).

By controlling the digital platforms through which communication and information is exchanged, the media’s gatekeeper power has evolved and changed focus. At the level of communications networks and digital platforms, gatekeeper power works to shape people’s access to news and media content (Winseck, 2022). Digital platforms are themselves “gates.” (1) Because media content increasingly passes through them, it means that already financially precarious news and entertainment media become further dependent on the digital corporations to distribute this content on the internet. These transactions then become a means to harvest and use personal information to sell to advertisers (and back to the content producers), which is the basis of the business model. (2) In addition, the more powerful internet, communication, and media companies become, the greater their ability to influence government regulation and set exploitative privacy and data protection policy norms that differ from what people say they want. (3) Finally, gatekeeper power stays intact to the degree that (a) the platforms’ algorithms sort, rank, recommend, or personalize information for users. As increased traffic means increased revenue, one effect of this has been to magnify divisive political and social positions which attract views and create algorithmically generated, self-confirming “echo chambers.” This has radically altered the nature of discourse in the public sphere and undermined evidence-based decision making. (b) The platforms also regulate which content and apps gain access to their operating systems and online retail spaces. “These are the ‘hidden levers of power’ that determine whether Alex Jones, Donald Trump or adult content on Tumblr stay up, come down, or are limited in their visibility” (Winseck, 2022).

Media Bias

Media bias refers to the bias of media content in the selection of the events and stories that are reported and how they are covered. Sometimes media bias is defined by explicit promotion of a particular political position, lack of objectivity and “balance,” the personal subjective bias of the content producer, or a transgression of professional standards. In critical sociology however, the focus is on the ways that bias in media messaging supports dominant economic and political structures of power while marginalizing dissent.

One prominent approach to media bias in critical sociology is Herman and Chomsky‘s (2008) propaganda model. They argue that “the media serve, and propagandize on behalf of, the powerful societal interests that control and finance them” (Herman and Chomsky, 2008). The authors argue that:

The mass media serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace. It is their function to amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behaviour that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. In a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfil this role requires systematic propaganda (Herman and Chomsky, 2008).

As Noam Chomsky (Achbar & Wintonick, 1992) clarifies, “all of this has nothing to do with liberal or conservative bias. According to the propaganda model, both liberal and conservative wings of the media, whatever those terms are supposed to mean, fall within the same framework of assumptions.” The focus of this critique of media bias is not on conservative vs. liberal media, but on how the dominant media discourses serve to “manufacture consent” to social inequality, corporate power and state interests.

Sometimes the bias of the news media is explicit, as with Fox News in the US. However, Herman and Chomsky (2008) describe a series of more subtle mechanisms or media filters through which “the powerful are able to fix the premise of discourse, to decide what the general populace is allowed to see hear and think about.” Specifically, they describe five filters:

- Ownership: The dominant media firms are large, concentrated corporate conglomerates. They have common interests with other major corporations, banks, and government, including the commitment to an economic system of market driven profit. These interests influence and constrain journalists, editors and media content.

- Advertising: The economic model of the media is based on generating revenue from advertising, giving advertisers the power to influence content. The media’s dependence on advertising makes it less likely that media will produce content that advertiser’s find offensive.

- Sourcing: The reliance on “trusted sources,” press releases, and news conferences often means using government or corporate spokespeople who spend vast sums on public relations, spin and lobbying. Using unofficial sources requires more work and these sources are often only consulted for reactions to, or minority positions on, news stories rather than being the primary source.

- Flak: Flak is the ability of financially or politically privileged actors to attack or legally harass journalists and sources who have provided critical media coverage or challenged official and corporate points of view.

- Ideology: The use of ideological filters like “anticommunism” during the Cold War period (1945–1989) mobilize the population against an enemy and are fuzzy enough to frame any criticism or alternate viewpoint of the system as an “Us versus Them” issue. Contemporary examples include the belief in the “the free market,” post 9-11 anti-terrorism discourses or attacking “wokeness.” Herman and Chomsky (2008) note that whenever the ideological filter is triggered, the normal requirement for rigorous journalistic evidence is suspended and charlatans, informers, and other opportunists can thrive as evidential sources and experts, even after their lack of credentials or truthfulness has been exposed.

Quantitative analyses of media have tried to see how changes in media ownership affect media content, particularly in relation to the issue of media bias (Winseck, 2022). Evidence regarding the link between media ownership and bias is “mixed and inconclusive” (Soderlund, Brin, Miljan & Hildebrandt, 2012), however, the research is premised on the idea that different owners will have different biases. The consistent finding of “no effect” between ownership and bias might be better seen as emblematic of how the media preserves the status quo (Gitlin, 1978), which is what Herman and Chomsky predict.

Another type of criticism of the propaganda model has to do with the degree to which the public is manipulated by the media. The focus on the production of biased media content tends to obscure the diverse range of audience responses to the information and perspectives they receive in the media. To be fair, Chomsky and Herman are clear that they are not discussing media effects — the idea that a biased media will necessarily produce a biased population — but media structure and performance — what the media does and what constraints it faces. “The propaganda model describes forces that shape what the media does; it does not imply that any propaganda emanating from the media is always effective” (Herman and Chomsky, 2008). Sociologists can turn to interpretive sociology to concentrate on the processes by which audiences take or create meaning from media texts.

Interpretive Sociology

In contrast to positivist and critical approaches to the media, interpretive sociology emphasizes the processes by which media producers and audiences actively create and interpret meanings in the media. As Brym et al. (2013) explain, “people are not just empty vessels into which the mass media pour a defined assortment of beliefs, values, and ideas.” Interpretive approaches to media emphasize that both media production and interpretation are social processes. Media producers take an active role in deciding how an event, idea or thing will be represented. Media audiences take an active role in figuring out what the meaning of a media product is and how they will “use” or incorporate it into their daily life. This approach contrasts with the functionalist and critical traditions that tend to see the media as a monolithic source of culture that either reinforces the core values of society or imposes an ideologically distorted representation of society.

In mediated societies, the media have become central agents in the creation and spread of symbols that become the basis for a shared understanding of society. Sociologists working in the symbolic interactionist perspective focus on this social construction of reality as an ongoing process of social interactions in which people subjectively create and understand reality. Media representations provide a key source of images, identities, characters, and ideas through which this social construction is accomplished. Consider kids enthusiastically acting out scenes from a TV show or movie they liked or a family watching the news and making comments on the events as they are reported.

Media and audiences construct reality in a number of interactive ways. For some audience members, the people they watch on a screen or meet with on social media forums can become a primary group: the small informal groups of people like families who are closest to them and most influential. For others, media provide reference groups: groups to which an individual compares himself or herself, and by which they judge their successes and failures. (See Chapter 5. Socialization on media as an agent of socialization).

Katz and Lazarfeld (1955) describe the two-step flow of communication in which an intermediary — an opinion leader or influencer — intervenes between the sender of a message and the audience. People do not simply change their attitudes and behaviours or go out and buy a product because the media tells them to. Instead, the influence often comes from a third party, usually a person of status seen as having greater access to information. The influencer is an authority able to filter, interpret and explain media messages to an audience (Mwengenmeir, 2014). It is the credibility of the film critic or Rotten Tomatoes rating that persuades the individual to shell out money to see a movie. It is a favourable impression by social media “thought leaders,” late show TV hosts, or religious leaders who expound on the messages released by politicians that sway people’s political beliefs.

Thought leaders and influencers have in fact become the center of a multibillion-dollar influencer marketing industry. Influencer marketing is a form of social media marketing that involves product placements and endorsements from online personalities who use their social media followers as a ready-made market. Internet stars on platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok are used to promote brand visibility, drive engagement, and impact purchasing decisions for millions of users. Global spending on influencer marketing stood at $16.4 billion U.S. in 2022, having more than doubled since 2019 (Dencheva, 2023). A key component of the influencer’s role in the two-step flow of communication is the establishment of their authenticity — a form of charismatic authority to make lifestyle suggestions to followers based on the perceived “realness” or truth of their messages (Hund, 2023). The influencer’s ability to express themselves “authentically” is typically not based on their credentials, expertise or training but by their perceived sincerity and ability to follow through on claims they make about themselves. In a mediated society where authenticity, trust and “realness” are elusive, and influence is sold as a commodity, the study of what makes an influencer authentic is a fascinating sociological topic.

Media Representations

Media representations are the main way in which people access information about the world beyond their immediate milieu. Representations refer to media “texts” (images, books, films, newspaper articles, television shows, tweets, internet memes, etc.) that use signs and symbols to stand in for, or re-present, directly lived experiences. The process of translation from “thing” to representation is central to understanding the role of media as an institution of cultural transmission. As Stuart Hall puts it, an “event must become a story before it can become a communicative event” (Hall, 1980). How do events become media stories and what happens to them when they do?

For example, in March 2013, two high school football players in Steubenville, Ohio, were convicted of sexually assaulting a 16-year-old girl who was drunk at a party. A reporter covering the trial described the verdict in terms of the damage done, not to the girl, but to the “two young men who had such promising careers” (Scowen, 2013). This is a case in which the raw event of the sexual assault, captured on film by bystanders and broadcasted on social media, was turned into a story about the young athletes and their promising careers, rather than a story about the crime committed against the young girl or sexual violence against women more generally.

The important point is that the story is not factually “untrue” or even deliberately biased; it can be taken to represent the reporter’s honest emotional reaction to the events. However, encoded into the story were messages about the importance of athletes in American society, the class background of the young men (i.e., their “promising careers”), and the stigmatized status of the young woman who had been drunk at the party. Not told in the story was an alternative set of meanings that would have focused more appropriately on the seriousness of sexual assault as a crime, the effect of assault as a traumatic experience on the victim, and the cultural attitudes that permitted the young men to think about the young woman in this way in the first place.

With respect to this example, the crucial point regarding the nature of the audience’s mediated experience of the event is that in the shift from the reporter’s immediate, emotional response to seeing the young men sentenced in court to the production and broadcast of the event as a media story is a process of encoding or messaging. Encoding is enacted in the decisions that the reporter and the media producers made about how to re-present the event as a story. Encoding is the act whereby the events or raw reality depicted in a story are turned into messages that convey specific cultural meanings or emphases. In a mediated culture, the audience often does not have direct access to the event; the audience only has access to the codes that turned the event into a story.

Making Connections: Big Picture

Codes of Violence

Earlier in the chapter, the idea that violence in the media impacts audiences was discussed as a media effect. This framework is based on a positivist or causal model of explanation in which media content is the independent variable or stimulus and audience response is the dependent variable. Generally, the evidence presented in research on media effects is statistical in nature, meaning that to the degree that a media effect can be demonstrated, not everyone who watches a violent program will become more aggressive, fearful, or insensitive. Instead the research shows an overall pattern of effects or tendencies that emerge across the sample. On balance, viewers become more aggressive, fearful, or insensitive.

The causal model of explanation is drawn from behaviouralism — a linear sequence of sender/message/receiver in which the message is a stimulus, and the reception is a measurable response in the audience. The interpretive approach has a different focus. For a media “effect” to take place it has to pass through the processes whereby the meanings of media texts are firstly created by the sender and secondly interpreted by the receiver. In other words, rather than modelling media effects as stimulus and response, interpretive sociology examines the processes of meaning construction and interpretation.

In interpretive sociology violence in the media can be examined with regard to the process of encoding. Hall (1980) writes, “representations of violence on the TV screen ‘are not violence but messages about violence’.” There is a difference between violent imagery as a stimulus and violent imagery as a meaning or message.

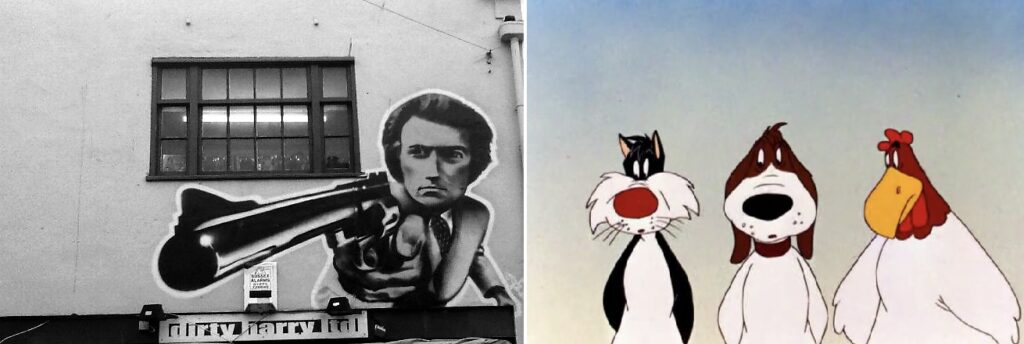

It could be argued that Dirty Harry and Foghorn Leghorn are equally violent in terms of the number of acts of violence they depict, but the messages about violence they convey are quite different. The violence is encoded differently. In the Dirty Harry movies of the 1970s, where the violence is drawn from the tradition of Hollywood film noir and action thrillers, the message is that a “true man” must follow his convictions, even by violence. Other styles of masculinity that involve non-violence, reason, internal reflection, duty, rational discussion, compromise, and respect for the law are somehow not true to the core of manhood. In the Foghorn Leghorn cartoons, where the violence is drawn from the tradition of carnival and slapstick comedy, the message of the violence is that those who are overly pompous or conceited will be cut down to size. The effect of these codes is to show violence as means of comic reversal in the fortunes of the characters.

Would the audience enjoy the violence in the Dirty Harry movies or identify with the hero, if they were fully conscious of their connection to toxic codes of masculinity or if the violence was real? Are viewers able to laugh at Foghorn Leghorn getting a kick in the butt if all they see is a painful or violent act, or a bad role model for children?

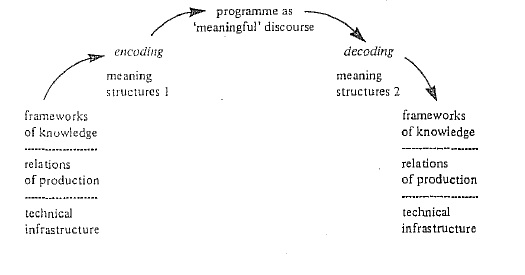

Decoding and Audience Reception

It is worthwhile to pursue Hall’s (1980) ideas a little further to get at the entire circuit of a media message (see Figure 16.x). The first step of the circuit describes the process of translation from event to story in a particular media outlet as a process of encoding. The events or raw reality depicted by the story are turned into messages that convey specific cultural meanings or emphases. These are the meaning structures 1 in Figure 16.26. Hall notes that this process takes place under specific conditions including the frameworks of knowledge used by the encoders (background knowledge that affects how they see or interpret the story), the relations of production of the encoders (workplace conditions, assigned tasks, market pressures, etc.), and the technical infrastructure used by the encoders (the types of media and technology used to present and circulate the story). These conditions all affect how the message is encoded.

Through the process of encoding the audience does not have direct access to the raw event through the media; they have access to a story about the event. The terms “event” and “story” are most appropriate to the discussion of media news stories, but the same principles apply to the creation of fictional stories about imagined events, the production of social media memes or the selection and presentation of visual images of actual people or places, etc. In each case, people are not only told what things are but what they mean. If a code is like a set of instructions for how to assemble the elements of a story into a coherent whole that makes sense to an audience (the programme as ‘meaningful’ discourse in Figure 16.26), in making choices about how to tell a story, the media can be seen to encode certain messages into their texts while excluding others.

On the other side of the process is audience reception: how the audience receives the media messages. Hall describes decoding as the process whereby the audience actively interprets or decodes the meaning of the story or media text. Sometimes this occurs through the intermediary of influencers, as discussed above, and sometimes not. In either case, the audience is not a passive recipient of media messages. Audiences are active in producing and receiving codes; they actively use codes to decode the messages in the media, receiving some messages and rejecting others. These are the meaning structures 2 in Figure 16.26.

These audience-produced codes are not necessarily the same as those used by the media producers. The audience uses its own frameworks of knowledge to interpret media texts and programs. These vary according to both individual factors such as sense of humour, perceptiveness, cultural knowledge, and social factors such as class (“relations of production” in Figure 16.26), gender, ethnicity, education, age, rural/urban location, etc.). By no means is it certain that the messages encoded by the media are those that are received by the audience. For example, a massive Twitter and Facebook reaction arose to the story about the sentencing of the young athletes in Steubenville, Ohio. For most of these commentators, the media’s focus on the damaged futures of the young men was a gross injustice considering the actual damage done to the young woman.

As a result, Hall (1980) describes the power of the media as a “complex structure in dominance.” While the media is a means of circulating the “dominant or preferred meanings” of a society, as both positivist and critical sociology suggest, there is no guarantee that these meanings are received, accepted, or reproduced by the audience. He suggests that there are at least three “hypothetical positions from which decodings of a televisual discourse can be constructed” (Hall, 1980). In other words, there are three general frameworks in which audiences interpret what they view on TV or other media:

- The dominant‐hegemonic position: When the viewer decodes the media text in terms of the dominant or preferred meanings of society. These are often the meanings that seem natural or common sense in a society. For example, in watching a political debate the viewer might lean one way or another in terms of their political party preference but accept the underlying premise that lowering corporate taxes to attract business investment to Canada is in the national interest. Or, they might watch a show in which Muslim characters are presented as fanatics and terrorists and not question the stereotypes because they fit an image reinforced by news reports or anti-terrorism ideological “filters,” not to mention the history of action thriller villains.

- The negotiated position: When the viewer largely accepts the dominant or preferred meanings of society but makes exceptions to the rule based on specific situations or local conditions. For example, the viewer might accept that attracting business investment to Canada is the goal of government at the level of the national interest but remember that subsidies and tax credits did not work to keep their local mill in operation. As a result, their politics “on the ground” might be quite different than the political positions they accept during national debates. Similarly, they might accept stereotypes about Muslims in the media they consume but not connect these stereotypes with the friendships they have with their Muslim neighbours or work colleagues.

- The oppositional position: When the viewer rejects the dominant or preferred meanings of society and replaces them with a set of oppositional meanings or an alternative frame of reference. For example, when the viewer who listens to the debate on the need to attract business investment interprets every mention of the ‘national interest’ as ‘ruling class interest’ they are decoding the debate from an oppositional position. Or, every time they see Muslims represented as fanatics and terrorists in a movie or TV show, they reinterpret the plot in terms of the history of colonization of the Middle East and Asia.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Functionalist, Critical, and Interpretive Approaches to Advertising Images

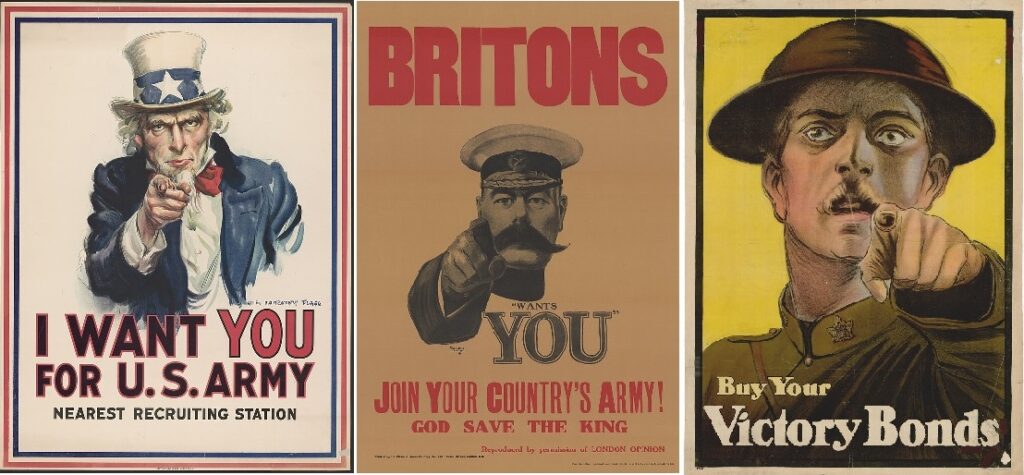

Advertisement is a specific type of media representation. It uses language and visual imagery to persuade an audience to do something, usually to buy a product, but in the posters above to enlist in the army or buy war bonds. As rhetoric is the art of using language to persuade or influence others, Roland Barthes (1977) refers to using photographs in advertising as “the rhetoric of the image.” This emphasizes that advertisement uses images to make an intentional or calculated message. Advertisers try to use the image to convey a specific set of messages to an audience about a product or campaign with the goal of convincing them to take action or hold some sort of belief. How can sociologists analyze the relationship between media and society through the study of advertising images?

Howard Becker (1974) argues that photographs contain a wealth of information of interest to sociologists.

“Every part of the photographic image carries some information that contributes to its total statement; the viewer’s responsibility is to see, in the most literal way, everything that is there and respond to it. To put it another way, the statement the image makes — not just what it shows you, but the mood, moral evaluation and causal connections it suggests — is built up from those details. A proper “reading” of a photograph sees and responds to them consciously.”

How might this approach to reading photographs be applied to reading advertisement communications? Functionalist, critical and interpretive sociologists would frame their reading in different ways.

The structural functionalist analysis focuses on identifying the functions of advertising. In commercial advertising the main function of ads is to inform consumers about a product to integrate the production of goods with their sale on the market (the social integration function). This is a key function in making a market economy work. In addition the ads perform other functions, like creating a consensus about the meaning of the product (solidarity function), socializing the audience about the norms and values of society (socialization function), or controlling the behaviour of audiences and consumers, i.e., to buy one product and not another (social control function).

In the three propaganda posters above the functions are similar except that instead of selling a product, they are performing the function of mobilizing the population to support the war effort though enlistment or buying war bonds. In each case, a fictional or real figure has been chosen to stand in for or symbolically embody the country or nation — Uncle Sam for the US, Lord Kitchener for the UK, a Canadian infantryman (Tommy Canuck) for Canada — and to bring out feelings of solidarity, unanimity and patriotic duty. It is interesting that the Canadian poster relied on an anonymous “everyman” figure as opposed to the mythic Uncle Sam or Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener. The infantryman serves as an emblem for sacrifice, nobility and purity but also Canadian modesty it would seem. Canada was a young country at the beginning of WW1, less than 50 years old, and did not have an established national identity or set of unifying “great” national traditions or symbols to draw from. In fact, many historians have argued that Canada’s experience in WW1 was a pivotal moment in the function of nation-building: the birth of Canada as an independent nation (Vance, 1997). The function of the Tommy Canuck image was to align the population with a unifying national identity and mobilize them to support the war effort.

Critical sociological approaches would examine the use of propaganda, nationalism and patriotism in these posters. They are instances of larger discourses of power in which the bottom line is citizens sacrificing their lives to obtain state objectives. In democracies, state objectives including war are represented as the will of the people, but when this will conflicts with instincts of self-preservation it has to be constructed and reinforced through propaganda and other means. The use of Uncle Sam, Lord Kitchener, and the Canadian infantryman to symbolize the unity of the nation, national interest and duty is one way to secure this consent. Instead of seeing WW1 as a struggle between rival European imperial powers over colonial expansion, a bloody war in which 61,000 Canadians died and 172,000 were wounded (Canadian War Museum, 2017), it becomes a war in which a “We” is threatened by a “Them.” Rather than a matter of critically examining the causes of the war, the stern pointing finger of each of the figures frames the issue of enlistment or war bonds at an emotional level as a matter of duty and heroic sacrifice. The pointing fingers imply that non-compliance would be an act of cowardliness and shirking. Contemporary efforts to describe WW1, or specific events like Vimy Ridge, as the birth of a nation, have also been used ideologically in attempts to rebrand Canada as a “warrior nation” rather than a “peacekeeper nation,” a precedent that would set Canada on the path to participating in future foreign wars rather than promoting diplomatic solutions (McKay and Swift, 2012).

Interpretive approaches focus on the different variables involved in interpreting and decoding the messages in the posters. Each poster addresses a “You,” both in the text and with the pointing finger. But who is the “You” who is being addressed exactly? The audience is not unified. Different segments of the population interpret the message differently according to their dominant, negotiated and oppositional positions. For example, the Uncle Sam figure, portrayed as a white northern Yankee, might alienate racialized Americans and southerners rather than unify them. Women would interpret the three posters differently than men because it was only men who were being asked to enlist or buy bonds. In fact, when mandatory conscription was announced in Canada in 1917, women’s support had to be enticed with the “Wartime Elections Act,” which allowed female relatives of soldiers to vote in federal elections. Women were in the position of having to witness the casualties of war, and they feared for the lives of partners and sons who were forced to enlist in the Canadian army. In Canada there were also deep divisions between the French in Quebec who felt no allegiance to defending Great Britain in the war, rural Canadians who needed human labour to work the fields, and English-speaking urban Canadians who largely supported the war. Each group interpreted the poster with a different set of concerns and meanings.

Finally, as images enter into popular culture and circulate they take on different meanings and associations. Fans of zombie movies might read a different set of meanings into the Tommy Canuck image in “Buy Your Victory Bonds” because of its remarkable resemblance to the zombie character played by Donald Sutherland in the final scene of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978). Zombie films have been used as metaphors for a variety of contemporary social issues, from the hazards of contemporary biotechnologies, to mindless consumerism, to the social disintegration of modern society. A zombie reading of Tommy Canuck might suggest that the mindless, devouring walking dead are symbols of patriotism and nationalism.

Media Attributions

- Figure 16.9 Guns of the Patriots – Tribute by Kevin Wong, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.10 Émile Durkheim-vignette-png-9 by verapatricia_28 [uploader], via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 16.11 Vintage Ad #457: Chew Vel-X by Jamie, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.12 Watching tv on my new setup.. woohoo HD tivo.. by Dennis Yang, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.13 Chart 2: Percent social media users attributing selected outcomes to their use of social media, by age group and smart phone use, Canada, 2018 by Schimmele et al. (2021) at Statistics Canada, is used under the Statistics Canada Open Licence.

- Figure 16.14 Happy with smart phone by cloud.shepherd, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.15 True Gangster Crime Cases. Vol. 2, no. 10 (November, 1940s) / True Gangster Crime Cases, vol. 2, no 10 (novembre, années 1940) by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

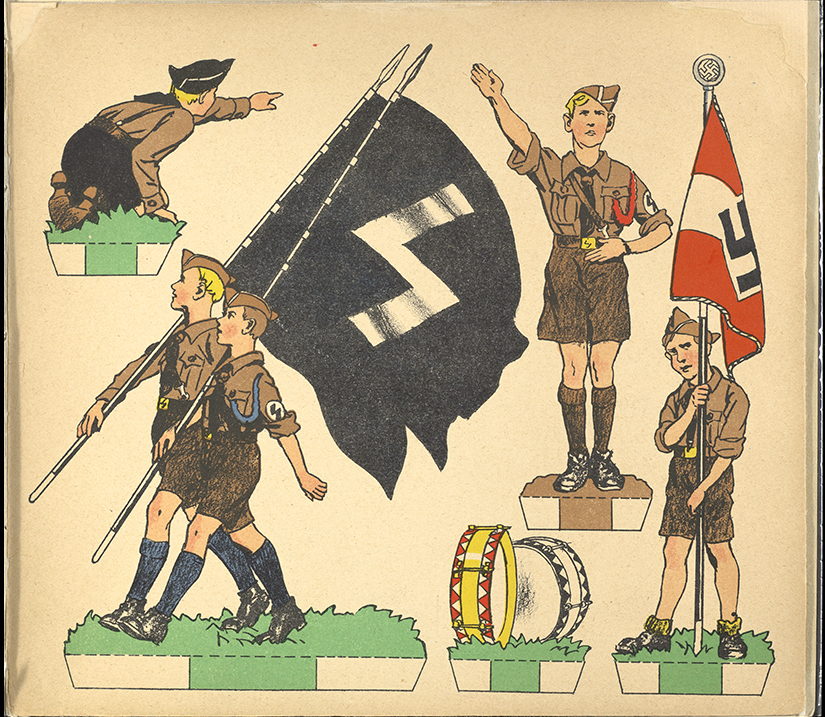

- Figure 16.16 1930s Nazi Germany propaganda children’s booklet cutout paper figures by unidentified artist/illustrator from the Weiner Holocaust Library, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 16.17 Camera Obscura, 1910 by Fizyka, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 16.18 Porträt einer Squaw by Will Soule, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 16.19 Figure 2: The Network Media Economy in Canada — What the CMCR Project Covers, in The Network Media Economy in Canada by D. Winseck (2022, p. 2) is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 16.20 The Top 50 Most Visited Websites in the World by Nick Routley and Joyce Ma is used by permission of Visual Capitalist.

- Figure 16.21 Noam Chomsky by Andrew Rusk, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.22 Vulcan cosplayer by Gage Skidmore, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.23 Polski: Domy Towarowe “Centrum” w 2000 roku by Cezary Piwowarsk, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a GNU Free Documentation Licence.

- Figure 16.24 Dirty Harry by Paul, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.25 Sylvester, Barnyard and Foghorn in “Crowing Pains” (1947) by Warner Bros, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 16.26 Figure 1 in Encoding/Decoding (Hall, 1980).

- Figure 16.27 Watching TV and joking around by Wonderlane, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.28 J. M. Flagg, I Want You for U.S. Army poster (1917) by J. M. Flagg, via Wikipedia, is in the public domain.