Chapter 19. The Sociology of the Body: Health and Medicine

19.3 Health in Canada

Health in Canada is a complex and often contradictory issue. On the one hand, as one of the wealthiest nations, Canada fares well in health outcomes with respect to the rest of the world. The publicly funded health care system in Canada also compares well to the noted issues of the private for-profit system in the United States (especially in terms of overall cost and who gets access to medical care). On the other hand, it is also behind many European countries in terms of key health care indicators such as access to family doctors and wait times for critical procedures. Choices about the model for delivering health care are one of the key variables affecting people’s health in a society.

The following sections look at different social determinants of health in Canada. The social determinants of health model emphasizes that social variables influence health outcomes for individuals and populations. Health and illness are not randomly distributed in a society. Their occurrence and prevalence are linked to the social organization of the society, particularly in terms of social inequality.

Social variables including race and ethnicity, gender, early childhood experiences, education, employment and working conditions, housing, income, social security policies, and access to health care produce different consequences for individual health. These variables impact health by affecting life chances, lifestyles, and life experiences. Social inequality determines who has access to resources such as adequate nutrition, satisfying work, recreation, and housing. As Navarro et al. (2004) argue, “a society’s socio-economic, political, and cultural variables are the most important factors in explaining the level of population health.”

Health by Race and Ethnicity

Unlike the United States, where strong health disparities exist along racial lines, differences in Canadians’ health between non-Indigenous visible minorities and Canadians of European origin disappear once socioeconomic status and lifestyle are taken into account. Moreover, new and recent immigrants from non-European countries tend to have better health than the average native-born Canadian (Kobayashi, Prus, and Lin, 2008).

Indigenous Canadians unfortunately continue to suffer disproportionately from serious health problems.

It is estimated that in the 1500s, prior to contact, there were 500,000 Indigenous people living in Canada, although estimates range from 200,000 to 2,000,000 (O’Donnell, 2008). Through epidemics of contagious Euro-Asian diseases such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and tuberculosis, Indigenous populations suffered an estimated 93% decline.

Conditions in the late 19th century to the mid-20th century did not improve markedly after Indigenous people were moved to reserves. Often lacking adequate drinking water, sanitation facilities, and hygienic conditions, these were ideal settings for the spread of communicable diseases. Death rates from tuberculosis (TB), for example, remained very high for First Nations peoples into the 1950s, long after the use of antibiotics brought TB under control in the rest of Canada. In 2005, the TB rate was still 27 active cases per 100,000 population for Indigenous people, while it was only five active cases per 100, 000 for the rest of the population.

Part of the problem is that the percentage of Indigenous people living in overcrowded housing on reserves and in the north is five to six times higher than for the general population (Statistics Canada, 2011). The crises in Attawapiskat, Ontario, and other First Nations communities with respect to housing, drinking water, and lack of proper water purification systems indicate that these issues have not been resolved (Stastna, 2011).

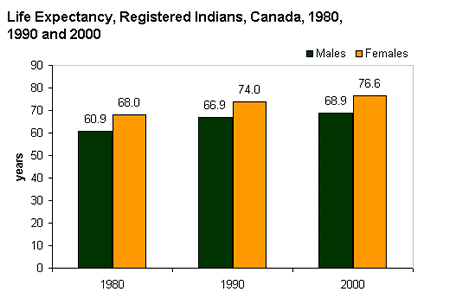

Figure 19.7 shows that life expectancy for Indigenous people (specifically Registered Indians) has improved. However, it remains significantly lower than for the average population: Indigenous men and women could expect to live 8.1 and 5.5 fewer years respectively than the average Canadian man and woman (Health Canada, 2005). While infectious diseases are largely regarded now as being under control in Indigenous populations (albeit at higher rates than the Canadian population), Indigenous people suffer disproportionately from chronic health problems like diabetes, heart disease, obesity, respiratory problems, and HIV (Statistics Canada, 2011).

The health conditions of off-reserve Indigenous people are also significantly worse than for the average population. While nearly 59% of non-Indigenous people in Canada over the age of 20 rated their health as “excellent or very good” in 2006–2007, only 51% of First Nations, 57% of Métis, and 49% of Inuit living off-reserve did so. Similarly, 74% of non-Indigenous Canadians reported they had no physical limitations due to ill health, while only 58, 59, and 64% of off-reserve First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, respectively, did so (Garner, Carrière, and Sanmartin, 2010). While some of the difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health conditions can be explained by financial, educational, and individual lifestyle variables, even when these were considered statistically, disparities in health remained. Garner, Carrière, and Sanmartin (2010) report that “[s]uch findings point to the existence of other factors contributing to the greater burden of morbidity among First Nations, Métis and Inuit people.”

Health by Socioeconomic Status

Ximena de la Barra, senior urban advisor to UNICEF, wrote in 1998 that “being poor is in itself a health hazard; worse, however, is being urban and poor” (de la Barra, 1998). The context of her statement was global urban poverty, but her conclusions apply to the relationship between poverty and health in Canada as well.

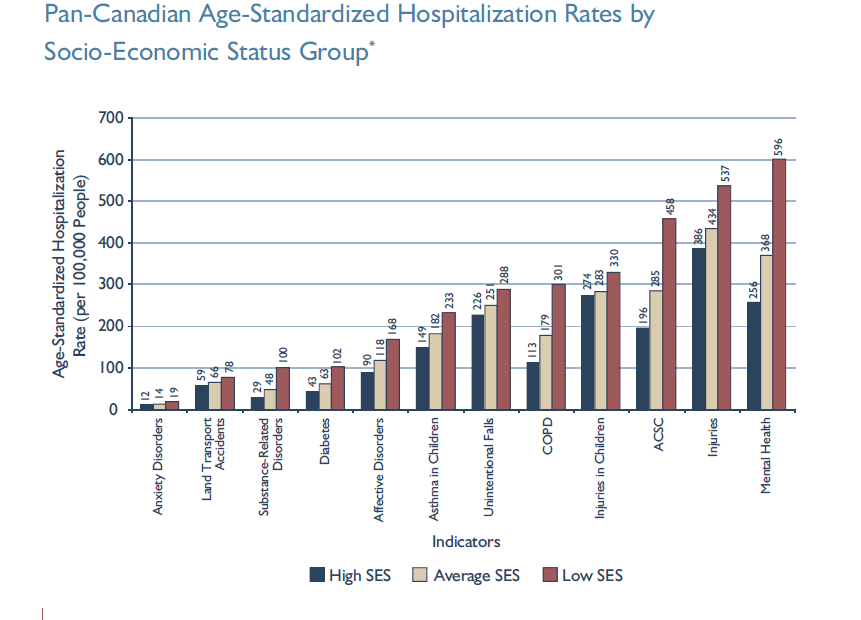

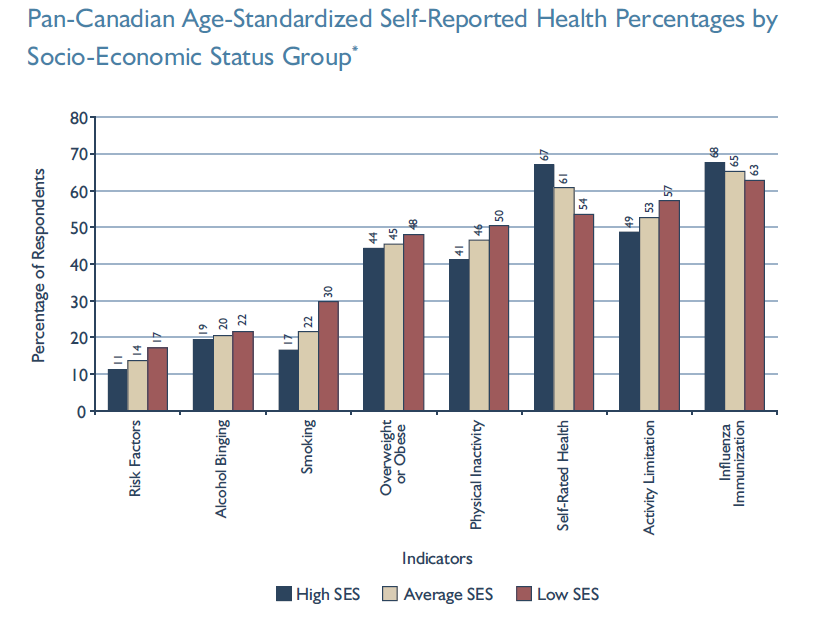

Residents of poorer urban areas within Canadian cities have significantly higher hospitalization rates and lower self-reported quality of health than residents of average or wealthy urban areas (see Figures 19.8 and 19.9).

Living and growing up in poverty is linked to lower life expectancy, and chronic illnesses such as diabetes, mental illness, stroke, cardiovascular disease, central nervous system disease, and injury (Canadian Population Health Initiative, 2008). In fact, clinical medical care accounts for only about a quarter of health outcomes, while one-half of a person’s ability to recover from illness is determined by socioeconomic factors, including income, education, and living conditions (CBC, 2014).

In an interesting study of 17, 350 British civil servants, it was found that differences in even relatively small disparities of wealth and power between civil service employment grades led to significantly better health outcomes for the privileged. The more authority one has, the healthier one is (Marmot, Shipley, and Rose, 1984). These social determinants of health led the Canadian Medical Association to argue that providing adequate financial resources might be the best medical treatment that can be provided to poor patients. Inner city doctor, Gary Bloch stated, “Treating people at low income with a higher income will have at least as big an impact on their health as any other drugs that I could prescribe them…. I do see poverty as a disease” (CBC, 2013).

It is important to remember that economics are only part of the socioeconomic status (SES) picture; research suggests that education also plays an important role. Phelan and Link (2003) note that many behaviour-influenced diseases like lung cancer (from smoking), coronary artery disease (from poor eating and exercise habits), and AIDS initially were widespread across SES groups. However, once information linking habits to disease was disseminated, these diseases decreased in high SES groups and increased in low SES groups. This illustrates the important role of education initiatives regarding a given disease, as well as possible inequalities in how those education initiatives effectively reach different SES groups.

Health by Gender

Women continue to live longer than men do on average, but women have higher rates of disability and disease. In each age group, men have higher rates of fatal disease, whereas women have higher rates of non-fatal chronic disease. “Women get sicker but men die quicker” might be a way of summing this up (Lorber, 2000). For example, while 4% of Canadian men suffer from chronic illnesses, these illnesses affect 11% of Canadian women, particularly conditions such as multiple sclerosis, lupus, migraines, hypothyroidism, and chronic pain (Spitzer, 2005).

Men’s lower life expectancy is often attributed to three factors: their tendency to engage in riskier behaviour or riskier work than women, their lower use of the health care system (which prevents symptoms from being diagnosed earlier), and their innate biological disposition to higher mortality at every stage of life. It is not as clear why chronic disease affects women in higher proportions. Spitzer (2005) notes that gender roles and relations lead to different responses and exposures to stressors, different access to resources, different responsibilities regarding domestic work and caregiving, and different levels of exposure to domestic violence, all of which might account for chronic health issues in women disproportionately.

Women are also affected adversely by institutionalized sexism in health care provision. An example of institutionalized sexism is the way that women are more likely to be diagnosed with certain kinds of mental disorders than men are. Psychologist Dana Becker notes that 75% of all diagnoses of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) are for women according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This diagnosis is characterized by instability of identity, of mood, and of behaviour, and Becker argues that it has been used as a catch-all diagnosis for too many women. She further decries the pejorative connotation of the diagnosis, saying that it predisposes many people, both within and outside of the profession of psychotherapy, against women who have been so diagnosed (Becker, N.d.).

Many critics also point to the medicalization of women’s issues as an example of institutionalized sexism. As noted earlier, medicalization refers to the process by which previously normal aspects of life are redefined as deviant and needing medical attention to remedy. Medicalization is therefore a form of disciplinary power in which doctors and medical knowledge become agents of social control (see discussion of disciplinary power in Chapter 8. Deviance, Crime and Social Control). Being under medical care means submitting to a regime of therapeutic intervention under the supervision of medical experts.

Historically and currently, many aspects of women’s lives have been medicalized, including menstruation, pre-menstrual syndrome, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause. The medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth has been particularly contentious in recent decades, with many women opting against the medical process and choosing a more natural childbirth. Fox and Worts (1999) find that all women experience pain and anxiety during the birth process, but that social support relieves both as effectively as medical support. In other words, medical interventions are no more effective than social ones at helping with the difficulties of pain and childbirth. Fox and Worts further found that women with supportive partners ended up with less medical intervention and fewer cases of postpartum depression. Of course, access to quality birth care outside of the standard medical models may not be readily available to women of all social classes.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Medicalization of Sleeplessness

How is your “sleep hygiene?” Sleep hygiene refers to the lifestyle and sleep habits that contribute to sleeplessness or insomnia. Bad habits that can lead to sleeplessness include inconsistent bedtimes, lack of exercise, late-night employment, napping during the day, and sleep environments that include noise, lights, or screen time (National Institutes of Health, 2011a).

According to the Toronto-based University Health Network, examining sleep hygiene is the first step in trying to solve a problem with sleeplessness (Bernstein and Durkee, 2008).

For many North Americans, however, making changes in sleep hygiene does not seem to be enough. According to a 2006 report, sleeplessness is an under-recognized public health problem affecting up to 70 million people. It is interesting to note that in the months (or years) after this report was released, advertising by the pharmaceutical companies behind Ambien, Lunesta, and Rozerem (three pharmaceutical sleep aids) averaged $188 million weekly promoting these drugs (Gellene, 2009).

According to Moloney, Konrad, and Zimmer (2011), prescriptions for sleep medications increased dramatically from 1993 to 2007. While complaints of sleeplessness during doctor’s office visits more than doubled during this time, insomnia diagnoses increased more than sevenfold, from about 840,000 to 6.1 million. The authors of the study conclude that sleeplessness has been medicalized as insomnia, and that “insomnia may be a public health concern, but potential overtreatment with marginally effective, expensive medications with nontrivial side effects raises definite population health concerns” (Moloney, Konrad, and Zimmer, 2011). Indeed, a study published in 2004 in the Archives of Internal Medicine shows that cognitive behavioural therapy, not medication, was the most effective sleep intervention (Jacobs, Pace-Schott, Stickgold, and Otto, 2004).

A century ago, people who could not sleep were told to count sheep. Now, they pop a pill, and all those pills add up to a very lucrative market for the pharmaceutical industry. Is this industry behind the medicalization of sleeplessness, or are they just responding to a need?

Mental Health and Disability

The treatment received by those defined as mentally ill or disabled varies greatly from country to country. In 21st century Canada, those who have never experienced such a disadvantage take for granted the rights Canadian society guarantees for each citizen. However, access to things like education, housing, or transportation that most people take for granted, are often experienced very differently by people with disabilities.

Mental Health

People with mental disorders have a condition that makes it more difficult to cope with everyday life. People with mental illness have a severe, lasting mental disorder that requires long-term treatment. In addition to the effects of the conditions, both must cope with social stigmas which impede full participation in social life.

According to the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey, the most common mental disorders in Canada are mood disorders (major depression, bipolar disorder). Over 11% of Canadians reported experiencing major episodes of depression in their lifetime (4.7% in the previous year), while 2.6% reported bipolar disorder in their lifetime (1.5% in the previous year) (Pearson, Janz, and Ali, 2013). Major mood disorders are depression, bipolar disorder, and dysthymic disorder. Depression might seem like something that everyone experiences at some point, and it is true that most people feel sad or “blue” at times in their lives. A truly depressive episode, however, is more than just feeling sad for a short period; it is a long-term, debilitating illness that usually needs treatment to cure. Bipolar disorder is characterized by dramatic shifts in energy and mood, often affecting the individual’s ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Bipolar disorder used to be called manic depression because of the way that people would swing between manic and depressive episodes.

The second most common mental disorders in Canada are anxiety disorders. Almost 9% of Canadians reported experiencing generalized anxiety disorder in their lifetime (2.6% in the previous year) (Pearson, Janz, and Ali, 2013). Like depression, it is important to distinguish between occasional feelings of anxiety and a true anxiety disorder. Anxiety is a normal reaction to stress that people all feel at some point, but anxiety disorders are feelings of worry and fearfulness that last for months at a time. Anxiety disorders include obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and both social and specific phobias.

Depending on what definition is used, there is some overlap between mood disorders and personality disorders. Canadian data on the prevalence of personality disorders is lacking but estimates in the United States suggest they affect 9% of Americans yearly. In Canada, epidemiological research reporting on antisocial personality disorder shows that about 1.7% of the population experience this specific disorder yearly (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2002). In the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual on Mental Disorders (DSM), personality disorders are defined as “an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the culture of the individual who exhibits it” (National Institute of Mental Health). In other words, personality disorders cause people to behave in ways that are seen as abnormal to society but seem normal to them. They manifest in constellations of maladaptive personality disorders including antisocial, avoidant, borderline, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality traits.

Another commonly diagnosed mental disorder is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which American statistics suggest affects 9% of children and 8% of adults on a lifetime basis (National Institute of Mental Health, 2005). The New York Times reported American Centers for Disease Control data showing that the diagnosis of children with ADHD had increased by 53% over the last decade, raising issues of overdiagnosis and overmedication (Schwarz and Cohen, 2013). Recent data from Canada confirm the increasing rate of prescribed medications and ADHD diagnosis in Canada, although the rates are much lower than those reported in the United States (3% for all children aged three to nine, but 4% for boys and 5% for school-aged children in this age range) (Brault and Lacourse, 2012). ADHD is one of the most common childhood disorders, and it is marked by difficulty paying attention, difficulty controlling behaviour, and hyperactivity. The significant increase in diagnosis and the use of medications such as Ritalin have prompted social debate over whether such drugs are being overprescribed (American Psychiatric Association, N.d.). In fact, some critics question whether this disorder is as widespread as it seems, or if it is a case of overdiagnosis.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have also gained a lot of attention in recent years. The term ASD encompasses a group of developmental brain disorders that are characterized by “deficits in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and engagement in repetitive behaviours or interests” (National Institute of Mental Health, 2011b). A report from the American Centers for Disease Control (CDC) suggests that 1 in every 68 children is born with ASD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). This diagnosis is up by 30% from the previous estimate that 1 in 88 children is born with ASD. In Canada, a national tracking system is being set up, but a report from the National Epidemiologic Database for the Study of Autism in Canada found increases in diagnosis in Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and southeastern Ontario ranging from 39 to 204 percent, depending on the region. As an example of social construction of disorders, much of the increase in diagnosis is believed to be due to increased awareness of the disorder rather than actual prevalence, with doctors diagnosing autism more frequently and with children with less severe problems (NEDSAC, 2012).

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) distinguishes between serious mental illness and other disorders. The key feature of serious mental illness is that it results in “serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities” (National Institute of Mental Health, 2005). Thus, the characterization of “serious” refers to the effect of the illness (functional impairment), not the illness itself.

Some researchers associated with the anti-psychiatry movement have argued that mental illness is a myth. For example, in Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Analysis (1963), Thomas Scheff argues that residual deviance — a violation of social norms not covered by any specific behavioural expectation — is what actually results in people being labelled mentally ill. Scheff proposed that what psychiatrists described as mental illnesses were in fact deviant behaviors that had become recognizable, definable, and stable through the practice of labelling. A “residual” deviance differed from “ordinary” deviance because they were norm violations that fell outside of normal moral, legal or folkway categories. They violated social norms that seem so universal and natural to a particular community that they were “neither verbalized nor explicitly taught” (Scheff, 1963).

Most norm violations do not cause the violator to be labelled as mentally ill, but as ill-mannered, ignorant, sinful, criminal, or perhaps just harried, depending on the type of norm involved. (Or potential definers may deny that the deviance even warrants labelling.) After exhausting these categories . . . there is always a residue of the most diverse kinds of violations for which the culture provides no explicit label. These are unnameable and unthinkable forms of deviance. . . . For convenience these violations are lumped together into a residual category: witchcraft, spirit possession, or, in our own society, mental illness (Scheff, 1963).

Similarly, in The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct (1961), Thomas Szasz asks if there is such a thing as mental illness at all, and then argues that there is not. Rather, mental illness is a deviation from what others view as normal, with no parallel to biological disease or illness. He was concerned about the institutional implications for individuals who deviated from societal norms or moral conduct. The tendency to forcibly detain, treat, or excuse individuals who simply violated behavioural codes undermined personal rights, personal dignity, and moral responsibility.

Disability

Disability refers to a reduction in one’s ability to perform everyday tasks. The World Health Organization makes a distinction between the various terms used to describe disabilities. They use the term impairment to describe physical limitations, while reserving the term disability to refer to the social limitation. In 2012, 3.8 million Canadians, or 13.7% of Canadians aged 15 and over, reported having a disability — a long-term condition or health-related problem — that limited their ability to perform daily tasks. Twenty-six per cent of these Canadians had a disability classified as “very severe” (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Lyn Jongbloed (2003) notes that conceptions of disability have gone through several shifts in Canada since the 19th century, leading to significant shifts in public policy on disabilities. In the early 19th century, persons with intellectual impairments were either cared for at home or jailed alongside criminals, suggesting that the distinction between crime and disability was not significant, at least from the point of view of public policy. People with physical disabilities were not regarded as disruptive so they were not institutionalized. Then between 1860 and 1890, the asylum model of care was developed specifically for people with disabilities, (including older persons with senility, intellectually impaired, mentally ill, or syphilis patients), in large part to protect them or others from harm.

This law-and-order approach was gradually replaced by medical and economic models that conceptualized disability as a biological reality that called for practices such as rehabilitation. Rehabilitation focused on interventions to treat or cure disabilities so that people with disabilities could earn a livelihood and reintegrate into “normal” society. As Jongbloed suggests, “Helping people become economically independent is consistent with the North American ideology of individualism. The economic model of disability is predicated on an individual’s inability to participate in the paid labour force” (2003).

Finally, since the 1970s, the medical and economic model has been gradually supplanted, or supplemented, by a sociopolitical model that argues that disability results from a failure of the social environment rather than individual impairment. This led to rights-based challenges of barriers to people with disabilities and a deinstitutionalization movement that saw the dismantling of the asylum system and its replacement with a community model of care.

Before the passage of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, which specifically designated individuals with disabilities as one of four disadvantaged groups protected by the Charter, Canadians with disabilities were often routinely excluded from opportunities and social institutions that many able-bodied persons take for granted. This occurred not only through employment and other kinds of discrimination, but through casual acceptance by most Canadians of a world designed for the convenience of the able-bodied. Imagine being in a wheelchair and trying to use a sidewalk without the benefit of wheelchair-accessible curbs. Imagine a blind person trying to access information without the widespread availability of Braille. Imagine having limited motor control and being faced with a difficult-to-grasp round door handle.

Ableism refers to both direct discrimination against persons with disabilities and the unintended neglect of their needs. It is not the physiological, mental, or medical nature of impairment that disables so much as the way the social world has been constructed to enable some, while disabling others.

Ableism is linked to the enduring legacy of stigmatizing persons with disabilities. People with disabilities are stigmatized by the perception that they are, in some manner, ill or less than fully human. The belief is that people with disabilities are incapable of living a full or good human life. As noted earlier in the chapter, Erving Goffman (1963) describes stigmatization as the process in which a person’s identity becomes “spoiled;” based on a difference in ability, they are labelled as wholly different, discriminated against, and sometimes even shunned. They are categorized and ascribed a master status, becoming “the blind girl” or “the boy in the wheelchair” instead of someone afforded a full identity by society. This can be especially true for people who are living with mental illness or if they are mentally impaired.

In response, many groups have begun to assert that they are not disabled, but differently enabled. Their condition is not a form of deviance from the norm, but a different form of normality. As Rod Michalko argues, blindness for example is only seen as a problem or disability from the point of view of sightedness and a world organized for the sighted (Michalko, 1998). Similarly, with respect to cognitive disabilities like autism spectrum disorders, groups with disabilities have proposed to replace stigmatization with a neurodiversity paradigm which emphasizes the fact of neurocognitive variation among the human species. Rather than an individual medical pathology, those who fall outside neurocognitive norms should be seen as “neuro-minorities” who have been marginalised by a “neuronormative” organisation of society in favour of the “neurotypical” (Chapman, 2020).

In a lecture to parents with Autism Spectrum children entitled “Don’t Mourn for Us”, autistic activist Jim Sinclair (2012) stated:

Autism isn’t something a person has, or a “shell” that a person is trapped inside. There’s no normal child hidden behind the autism. Autism is a way of being. It is pervasive; it colours every experience, every sensation, perception, thought, emotion, and encounter, every aspect of existence. It is not possible to separate the autism from the person — and if it were possible, the person you’d have left would not be the same person you started with.

As discussed in the section on mental health, many mental health disorders can be debilitating, affecting a person’s ability to cope with everyday life. This can affect social status, housing, and especially employment. According to the Canadian Human Rights Commission’s Report on Equity Rights of People with Disabilities (2012), people with a disability had a higher rate of unemployment than people without a disability: 8.6% to 6.3% (2006 data). Men and women with disabilities are also 8.6% and 6.5% more likely to be underemployed than men and women without disabilities (respectively). People with disabilities were also only half as likely to complete a university education as those without disabilities (20.2% versus 40.7%, respectively), and are earning or earned significantly less ($9,557 less per year for men and $8,853 less for women). Note, this data does not consider non-binary genders.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Obesity: The Last Acceptable Prejudice

What is the typical reaction to the picture in Figure 19.13? Compassion? Fear? Disgust? Many people will look at this picture and make negative assumptions about the man based on his weight. According to a study from the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, large people are the object of “widespread negative stereotypes that overweight and obese persons are lazy, unmotivated, lacking in self-discipline, less competent, noncompliant, and sloppy” (Puhl and Heuer, 2009).

Historically, in Canada and elsewhere, it was considered acceptable to discriminate against people based on prejudiced opinions. Even after the colony status of Canada formally ended with the formation of the Canadian state in 1867, the next 100 years of Canadian history saw institutionalized racism and prejudice against Indigenous people. In an example of stereotype interchangeability, the same insults that are flung today at the overweight and obese population (lazy, for instance), have been flung at various racial and ethnic groups in earlier history. Of course, no credible person gives voice to these kinds of views in public now, except when talking about obese people.

Why is it considered acceptable to feel prejudice toward — even to hate — obese people? Puhl and Heuer suggest that these feelings stem from the perception that obesity is preventable through self-control, better diet, and more exercise. Highlighting this contention is the fact that studies have shown that people’s perceptions of obesity are more positive when they think the obesity was caused by non-controllable factors like biology (a thyroid condition, for instance) or genetics.

Even with some understanding of non-controllable factors that might affect obesity, obese people are still subject to stigmatization. Puhl and Heuer’s study is one of many that document discrimination at work, in the media, and even in the medical profession. Obese people are less likely to get into college than thinner people, and they are less likely to succeed at work.

Stigmatization of obese people comes in many forms, from the seemingly benign to the potentially illegal. In movies and television shows, overweight people are often portrayed negatively, or as stock characters who are the butt of jokes. One study found that in children’s movies “obesity was equated with negative traits (evil, unattractive, unfriendly, cruel) in 64%of the most popular children’s videos. In 72% of the videos, characters with thin bodies had desirable traits, such as kindness or happiness” (Hines and Thompson, 2007). In movies and television for adults, the negative portrayal is often meant to be funny. “Fat suits” —inflatable suits that make people look obese — are commonly used in a way that perpetuates negative stereotypes. Think about the parallel with white people putting on “blackface” or the way obese people are portrayed in movies and on television. Is there any other subordinate group that can be openly denigrated in such a way? It is difficult to find a parallel example.

Image Description

| Date | Male life expectancy | Female life expectancy |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 60.9 years | 68.0 years |

| 1990 | 66.9 years | 74.0 years |

| 2000 | 68.9 years | 76.6 years [Return to Figure 19.7] |

Media Attributions

- Figure 19.7 Life Expectancy, Registered Indians, Canada, 1980, 1990 and 2000 from Health Canada (2005). Data source: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2001, Basic Departmental Data 2001, Catalogue no. R12-7/2000E. This reproduction is a copy of an earlier version. Statistics Canada Open Licence

- Figure 19.8. Figure 3A. Pan-Canadian Age-Standardized Hospitalization Rates by Socio-Economic Status Group [PDF]. from Canadian Population Care Initiative (2008), is used according to the Government of Canada Terms.

- Figure 19.9. Figure 3B. Pan-Canadian Age-Standardized Self-Reported Health Percentages by Socio-Economic Status Group [PDF]. from Canadian Population Care Initiative (2008), is used according to the Government of Canada Terms.

- Figure 19.10 Sleeping students, by Love Krittaya, via Wikimedia Commons, has been released into the public domain by its author.

- Figure 19.11 Tramadol, by Deviation56 at English Wikipedia, via Wikimedia Commons, has been released into the public domain by its author.

- Figure 19.12 Handicapped Accessible sign by Ltljltlj, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain because it comes from the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, sign number D9-6.

- Figure 19.13 Epidemic by Tony Alter on Flickr under a CC BY 2.0 licence.