Chapter 3. Culture

3.1. What Is Culture?

Humans are social creatures. Since the dawn of Homo sapiens, nearly 200,000 years ago, people have grouped together into communities in order to survive. Living together, people developed forms of cooperation which created the common habits, behaviours, and ways of life known as culture — from specific methods of childrearing to preferred techniques for obtaining food. Peter Berger (b. 1929) argued that culture is the product of a fundamental human predicament (1967). Unlike other animals, humans lack the biological programming to live on their own. They require an extended period of dependency in order to survive in the environment. The creation of culture makes this possible by providing a kind of protective shield against the harsh impositions of nature. Culture provides the ongoing transmission of knowledge and stability that enables human existence. It allows humans to know that one plant is poisonous and another plant is edible, and so on. This means, however, that the human environment is not nature per se but culture itself. Humans live in a world defined by culture.

Over the history of humanity, this has lead to an incredible diversity in how humans have imagined and lived life on Earth, the sum total of which Wade Davis (b. 1953) has called the ethnosphere. The ethnosphere is the entirety of all cultures’ “ways of thinking, ways of being, and ways of orienting oneself on the Earth” (Davis, 2007). It is the collective cultural heritage of the human species. A single culture, as the sphere of meanings shared by a single social group, is the means by which that group makes sense of the world and of each other. But there are many cultures and many ways of making sense of the world. Through a multiplicity of cultural inventions, human societies have adapted to the environmental and biological conditions of human existence in many different ways. What do we learn from this?

First, almost every human behaviour, from shopping to marriage to expressions of feelings, is learned. In Canada, people tend to view marriage as a choice between two people based on mutual feelings of love. In other nations and in other times, marriages have been arranged through an intricate process of interviews and negotiations between entire families, or in other cases, through a direct system such as a mail-order bride. To someone raised in Winnipeg, the marriage customs of a family from Nigeria may seem strange or even wrong. Conversely, someone from a traditional Kolkata family might be perplexed with the idea of romantic love as the foundation for the lifelong commitment of marriage. In other words, the way in which people view marriage depends largely on what they have been taught. Being familiar with these written and unwritten rules of culture helps people feel secure and “normal.” Most people want to live their daily lives confident that their behaviours will not be challenged or disrupted. Behaviour based on learned customs is, therefore, a good thing, but it does raise the problem of how to respond to cultural differences.

Second, culture is innovative. The existence of different cultural practices reveals the way in which societies find different solutions to real life problems. The different forms of marriage are various solutions to a common problem, the problem of organizing families in order to raise children and reproduce the species. As structural functionalists argue, the basic problem is shared by the different societies, but the solutions are different. This illustrates the point that culture in general is a means of solving problems. It is a tool composed of the capacity to abstract and conceptualize, to cooperate and coordinate complex collective endeavours, and to modify and construct the world to suit human purposes. It is the repository of creative solutions, techniques, and technologies humans draw on when confronting the basic shared problems of human existence. Culture is, therefore, key to the way humans, as a species, have successfully adapted to the environment. The existence of different cultures refers to the different means by which humans use innovation to free themselves from biological and environmental constraints.

Third, culture is also restraining. Cultures retain their distinctive patterns through time and impose them on their members. In contemporary life, global capitalism increasingly imposes a common cultural playing field on the cultures of the world. As a result, Canadian culture, French culture, Malaysian culture, and Kazakhstani culture will share certain features like rationalization and commodification, even if they also differ in terms of languages, beliefs, dietary practices, and other ways of life. There are two sides to the response of local cultures to global culture. Different cultures adapt and respond to capitalism in unique manners according to their specific shared heritages. Local cultural forms have the capacity to restrain the changes produced by globalization. Moreover, unique local cultures are transported around the world due to global migration, diasporas and media, leading to the diversification of cultural practices in countries like Canada, as well as to innovative forms of cultural blending and hybridization. On the other hand, the diversity of local cultures is increasingly limited by the homogenizing pressures of globalization. Economic practices that prove inefficient or uncompetitive in the global market disappear. The meanings of cultural practices and knowledges change as they are turned into commodities for tourist consumption or are patented by pharmaceutical companies. Globalization also increasingly restrains cultural forms, practices, and possibilities.

There is therefore a dynamic within culture of innovation and restriction. The cultural fabric of shared meanings and orientations that allows individuals to make sense of the world and their place within it can change with contact with other cultures and changes in the socioeconomic formation, allowing people to reinvision and reinvent themselves. Or, it can remain stable, even rigid, and restrict change. Many contemporary issues to do with identity and belonging, from multiculturalism and hybrid identities to religious fundamentalism and white nationalist movements, can be understood within this dynamic of innovation and restriction. Similarly, the effects of social change on ways of life, from new modes of electronic communication to societal responses to climate change and global pandemics, involve a tension between innovation and restriction.

Making Connections: Big Picture

“Yes, but what does it mean?”

When asked how to diagnosis illness by observing external signs, Qi Bo replied: “You can determine the form of the illness by examining the chi to see if it is relaxed or tense, small or large, slippery or rough, and by feeling whether the flesh is firm or flabby…. If the skin of the chi is slippery, lustrous, oily, you are dealing with wind. If the skin of the chi is rough, you are dealing with wind induced paralysis” (cited in Kuriyama, 1999).

A doctor trained in Western biomedicine would probably not have a clue what Qi Bo was talking about. Even though the operation of the human body would seem universally the same no matter the cultural context, “accounts of the body in diverse medical traditions frequently appear to describe mutually alien, almost unrelated worlds” (Kuriyama, 1999). Why?

The sociology of culture is concerned with the study of how things and actions assume meanings, how these meanings orient human behaviour, and how social life is organized around and through meaning. It proposes that the human world, unlike the natural world, cannot be understood unless its meaningfulness for social actors is taken into account. Human social life is necessarily conducted through the meanings humans attribute to things, actions, others, and themselves. Human experience is essentially meaningful, and culture is the source of the meanings that humans share.

What this implies is that people do not live in direct, immediate contact with the world and each other. Their lives are not governed by the effects of physical stimuli or genetic programming. Instead, they live only indirectly through the medium of the shared meanings provided by culture. This mediated experience is the experience of culture. As the philosopher Martin Heidegger (1995 /1929–1930) put it, humans uniquely live in an “openness” to the world granted by language and by their ability to respond to the meaningfulness of things in a way that other living beings do not.

Max Weber (1968) notes that it is possible to imagine situations in which human experience appears direct and unmediated; for example, a doctor taps a patient’s knee and their leg jerks forward, or a bicyclist is riding their bike and gets hit by a car. In these situations, experience seems purely physical, unmediated. Yet when people assimilate these experiences into their lives, they do so by making them meaningful events. By tapping a person’s knee, the doctor is interpreting signs that indicate the functioning of their nervous system. She or he is literally reading the reactions as symbolic events and assigning them meaning within the context of an elaborate cultural map of meaning: the modern biomedical understanding of the body. It is quite possible that if the bicyclist was flying through the air after being hit by a car, they would not be thinking or attributing meaning to the event. They would simply be a physical projectile. But afterwards, when they reconstruct the story for their friends, the police, or the insurance company, the event becomes part of their life through the way they put what happened into a narrative.

Equally important to note here is that the meaning of these events changes depending on the cultural context. A doctor of traditional Chinese medicine would read the knee reflex differently than a graduate of the UBC medical program. The story and meaning of the car accident changes if it is told to a friend as opposed to a policeman or an insurance adjuster.

The problem of meaning in sociological analysis, then, is to determine how events or things acquire meaning (e.g., through the reading of symptoms or the telling of stories); how the true or right meanings are determined (e.g., through pulse diagnosis, biomedical tests, or legal procedures of determining responsibility); how meaning works in the organization of social life (e.g., through the medicalized relation individuals have to their bodies or the rules governing traffic circulation); and how humans gain the capacity to interpret and share meanings in the first place (e.g., through the process of socialization into medical, legal, insurance, and traffic systems). Sociological research into culture studies all of these problems of meaning.

Culture and Biology

The central argument put forward in this chapter is that human social life is essentially meaningful and, therefore, has to be understood first through an analysis of the cultural practices and institutions that produce meaning. Nevertheless, a fascination in contemporary culture persists for finding biological or genetic explanations for complex human behaviours that would seem to contradict the emphasis on culture.

In one study, Swiss researchers had a group of women smell unwashed T-shirts worn by different men. The researchers argued that sexual attraction had a biochemical basis in the histo-compatibility signature that the women detected in the male pheromones left behind on the T-shirts. Women were attracted to the T-shirts of the men whose immune systems differed from their own (Wedekind et al., 1995). In another study, Dean Hamer and his colleagues discovered that some homosexual men possessed the same region of DNA on their X chromosome, which led them to argue that homosexuality was determined genetically by a “gay gene” (Hamer et al., 1993). Another study found that the corpus callosum, the region of nerve fibres that connect the left and right brain hemispheres, was larger in women’s brains than in men’s (De Lacoste-Utamsing & Holloway, 1982). Therefore, women were thought to be able to use both sides of their brains simultaneously when processing visuo-spatial information, whereas men used only their left hemisphere. This finding was said to account for gender differences that ranged from women’s supposedly greater emotional intuition to men’s supposedly greater abilities in math, science, and parallel parking. In each of these three cases, the authors reduced a complex cultural behaviour — sexual attraction, homosexuality, cognitive ability — to a simple biological determination.

In each of these studies, the scientists’ claims were quite narrow and restricted in comparison to the conclusions drawn from them in the popular media. Nevertheless, they follow a logic of explanation known as biological determinism, which argues that the forms of human society and human behaviour are determined by biological mechanisms like genetics, instinctual behaviours, or evolutionary advantages. Within sociology, this type of framework underlies the paradigm of sociobiology, which provides biological explanations for the evolution of human behaviour and social organization.

Sociobiological propositions are constructed in three steps (Lewontin, 1991). First, they identify an aspect of human behaviour which appears to be universal, common to all people in all times and places. In all cultures the laws of sexual attraction — who is attracted to whom — are mysterious, for example. Second, they assume that this universal trait must be coded in the DNA of the species. There is a gene for detecting histo-compatibility that leads instinctively to mate selection. Third, they make an argument for why this behaviour or characteristic increases the chances of survival for individuals and, therefore, creates reproductive advantage. Mating with partners whose immune systems complement your own leads to healthier offspring who survive to reproduce your genes. The implication of the sociobiological analysis is that these traits and behaviours are fixed or “hard wired” into the biological structure of the species and are, therefore, very difficult to change. People will continue to be attracted to people who are not “right” for them in all the ways we would deem culturally appropriate — psychologically, emotionally, socially compatible, etc. — because they are biologically compatible.

Despite the popularity of this sort of reason, it is misguided from a sociological perspective for a number of reasons. For example, Konrad Lorenz’s (1903-1989) arguments that human males have an innate biological aggressive tendency to fight for scarce resources, protect territories and secure access to sexual reproduction were very popular in the 1960s (Lorenz, 1966). Young males of reproductive age commit the most violence, so the argument is that male aggression is an inborn biological tendency selected by evolutionary pressures as a result of struggles for reproductive dominance (Daly and Wilson, 1988). The pessimistic dilemma Lorenz posed was that males’ innate tendency towards aggression as a response to external threats might be a useful trait on an evolutionary scale, but in a contemporary society that includes the development of weapons of mass destruction, it is a threat to human survival. Another implication of his argument was that if aggression is instinctual, then the idea that individuals, militant groups, or states could be held responsible for acts of violence or war loses its validity. Ultimately, the evolutionary explanation of violence means that there is no point in trying change it, despite the sociological and historical evidence that aggression in individuals and societies can be changed. (Note here that Lorenz’s basic claim about aggression runs counter to the stronger argument that, if anything, the tendency toward co-operation has been central to the survival of human social life from its origins to the present).

However, a central problem of sociobiology as a type of sociological explanation is that while human biology does not vary greatly throughout history or between cultures, the forms of human association do vary extensively. It is difficult to account for the variability of social phenomena by using a universal biological mechanism to explain them. Even something like the aggressive tendency in young males, which on the surface has an intuitive appeal, does not account for the multitude of different forms and practices of aggression, let alone the different social circumstances in which aggression is manifested or provoked. Aggression is, of course, not exclusive to young males. It does not account for why some men are aggressive sometimes and not at other times, or why some men are not aggressive at all. It does not account for women’s aggression and the forms in which this typically manifests, which tend to be more indirect, social, and verbal forms of aggression (gossip, exclusion, character defamation, etc.). In fact, evidence suggests that violence between children (prior to reproductive age) is greater than at any other age, and often involves the aggressiveness of young girls, even if girls’ aggression is gradually restricted through socialization as they age (Tremblay et al., 2004). If production of testosterone is the key mechanism of male aggression, it does not account for the fact that both men and women generate testosterone. Nor does it explain the universal tendencies of all societies to develop sanctions and norms to curtail violence.

To suggest that aggression is an innate biological characteristic means that it does not vary greatly throughout history, nor between cultures, and is impervious to the social rules that restrict it in all societies. Yet as Randall Collins (2008) notes from a micro-sociological perspective, the factor that needs to be explained is not the natural tendency to aggression by young men, but the unique social circumstances required for them to be able to overcome the barriers of “confrontational tension and fear” that make aggression and violence difficult. The evolutionary argument suggests that violence should be easy for young men, whereas the research indicates that it is very hard and attempts to be violent often end in failure.

The main consideration to make here is not that biology has no impact on human behaviour, but that the biological explanation is limited with respect to what it can explain about complex cultural behaviours and practices. For example, research has shown that newborns and fetuses as young as 26 weeks have a simple smile: “the face relaxes while the sides of the mouth stretch outward and up” (Fausto-Sterling, 2000). This observation about a seemingly straightforward biological behaviour suggests that smiling is inborn, a muscular reflex based on neurological connections. However, the smile of the newborn is not used to convey emotions. It occurs spontaneously during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Only when the baby matures and begins to interact with their environment and caretakers does the smile begin to represent a response to external stimuli. By age one, the baby’s smile conveys a variety of meanings, depending on the social context, including flirting and mischief. Moreover, from the age of 6 months to 2 years, the smile itself changes physically: Different muscle groups are used, and different facial expressions are blended with it (surprise, anger, excitement). The smile becomes more complex and individualized. The point here, as Anne Fausto-Sterling (2000) points out, is that “the child uses smiling as part of a complex system of communication,” which is learned. Not only is the meaning of the smile defined in interaction with the social context, but the physiological components of smiling (the nerves, muscles, and stimuli) also are modified and “socialized” according to culture.

Therefore, social scientists see explanations of human behaviour based on biological determinants as extremely limited in scope and value. The physiological “human package” — bipedalism, omnivorous diet, language ability, brain size, capacity for empathy, lack of an estrous cycle (Naiman, 2012) — is more or less constant across cultures; whereas, the range of cultural behaviours and beliefs is extremely broad. These occasionally radical differences between cultures have to be accounted for instead by the distinct processes of socialization through which individuals learn how to participate in their societies. From this point of view, as the anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) put it:

We are forced to conclude that human nature is almost unbelievably malleable, responding accurately and contrastingly to contrasting cultural conditions. The differences between individuals who are members of different cultures, like the differences between individuals within a culture, are almost entirely to be laid to differences in conditioning, especially during early childhood, and the form of this conditioning is culturally determined (1935).

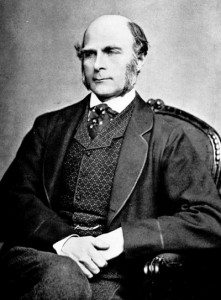

Aside from the explanatory problems of biological determinism, it is important to bear in mind the social consequences of biological determinism, as these ideas have been used to support rigid cultural ideas concerning race, gender, disabilities, etc. that have their legacy in slavery, racism, gender inequality, eugenics programs, and the sterilization of “the unfit.” Eugenics, meaning “well born” in ancient Greek, was a social movement that sought to improve the human “stock” through selective breeding and sterilization. Its founder, Francis Galton (1822-1911) defined eugenics in 1883 as “the study of the agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally” (Galton as cited in McLaren, 1990). In Canada, eugenics boards were established by the governments of Alberta and British Columbia to enable the sterilization of the “feeble-minded.” Based on a rigid cultural concept of what a proper human was, and grounded in the biological determinist framework of evolutionary science, 4,725 individuals were proposed for sterilization in Alberta and 2,822 of them were sterilized between 1928 and 1971. The racial component of the program is evident in the fact that while First Nations and Métis peoples made up only 2.5% of the population of Alberta, they accounted for 25% of the sterilizations. Several hundred individuals were also sterilized in British Columbia between 1933 and 1979 (McLaren, 1990).

The interesting question that these biological explanations of complex human behaviour raise is: Why are they so popular? What is it about our culture that makes the biological explanation of behaviours or experiences like sexual attraction, which we know from personal experience to be extremely complicated and nuanced, so appealing? As micro-biological technologies like genetic engineering and neuro-pharmaceuticals advance, the very real prospect of altering the human body at a fundamental level to produce culturally desirable qualities (health, ability, intelligence, beauty, etc.) becomes possible, and, therefore, these questions become more urgent.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The Pop Gene

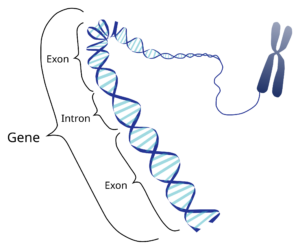

The concept of the gene and the idea of genetic engineering have entered into popular consciousness in a number of strange and interesting ways, which speak to our enduring fascination with biological explanations of human behaviour. Some sociologists have begun to speak of a new eugenics movement in reference to the way the mapping and testing of the genome makes it possible, as a matter of consumer choice, to manipulate the genes of a foetus or an egg — to eliminate what are considered birth “defects” or to produce what are considered desired qualities in a child (Rose, 2007). If the old eugenics movement promoted selective breeding and forced sterilization in order to improve the biological qualities and, in particular, the racial qualities of whole populations, the new eugenics is focused on calculations of individual risk or individual self-improvement and self-realization. In the new eugenics, individuals choose to act upon the genetic information provided by doctors, geneticists, and counselors to make decisions for their children or themselves.

This movement is based both on the commercial aspirations of biotechnology companies and the logic of a new biological determinism or geneticism, which suggests that the qualities of human life are caused by genes (Rose, 2007). The concept of the gene is a relatively recent addition to the way in which people begin to think about themselves in relationship to their bodies. The German historians Barbara Duden and Silja Samerski argue that the gene has become a kind of primordial reference point for the fundamental questions people ask about themselves (2007): Where do I come from? Who am I? What will happen to me in the future? The gene has shifted from its specific place within the parameters of medical science to become a source of popular understanding and speculation: a “pop gene.” Most tellingly, the gene has become a Trojan horse through which “risk consciousness” is implanted in people’s bodies. People begin to worry and make decisions about their lives and medical care based on the perceived risks embedded in their genetic make-up. The popularization of the idea of the gene entails the development of a new relationship to the human body, health, and the genetic predispositions to health risks as people age.

In 2013, the movie star Angelina Jolie underwent a double mastectomy, not because she had breast cancer but because doctors estimated she had an 87% chance of developing breast cancer due to a mutation in the BRCA1 gene (Jolie, 2013). On the basis of what might happen to her based on probabilities of risk from genetic models, she decided to take drastic measures to avoid the breast cancer that caused her mother’s death. Her very public stance on her surgery was to raise public awareness of the genetic risks of cancers that run in families and to normalize a medical procedure that many would be hesitant to take. At the same time she further solidified a notion of the gene as a site of invisible risk in peoples lives, encouraging more people to think about themselves in terms of their hidden dispositions to genetically programmed diseases.

Many misconceptions exist in popular culture about what a gene actually is or what it can do. Some of these misconceptions are funny — Duden and Samerski cite a hairdresser they interviewed as saying that her nail biting habit was part of the genetic programming she was born with — but some of them have serious consequences that can lead to the impossible decisions some individuals, including couples who are having a child, are forced to make. Informed decision making in genetic counseling often works with statistical probabilities of “defects” based on population data (e.g., “With your family history, you have a 1 in 10 chance of having a child with the genetic mutation for Down’s syndrome”), but what does this mean to a particular individual? The actual causal mechanism for that particular individual is unknown and it is unlikely that they will actually have 10 children, one of whom might have Down’s syndrome; therefore, what does this probability figure mean to someone who is pregnant? In this sense, the gene defines a set of cultural parameters by which people in the age of genetics make sense of themselves in relationship to their bodies. Like biological determinism in general, the gene introduces a kind of fatalism into the understanding of human life and human possibility.

Cultural Universals

Often, a comparison of one culture to another will reveal obvious differences. But all cultures share common elements. Cultural universals are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies. One example of a cultural universal is the kinship system: Every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children (See Chapter 14. Marriage and Family). In comparison to primate kinship however, human kinship configurations recognize a far wider range of recognized kin including matrilineal and patrilineal members (mother’s and father’s side relatives), several generations of family members, and members who live together as well as those who do not (Chapais, 2014). So what exactly is universal about kinship?

The significance of different types of relative varies and can be extremely complex — traditional Chinese kinship nomenclature has separate names for maternal and paternal lineages, relative age of siblings, gender of relatives, and nine generations of relative — but all human societies recognize a similar range of relations as kin. Four universal features of kinship systems include:

- A lengthy childhood maturation process that requires at least one adult to commit to prolonged child nurturing and educating;

- The presence of a socially recognized bond between two (or more) people that regulates their sexual and domestic relationship through time;

- A gender based division of labour within the household; and

- An incest taboo that prohibits sexual intercourse between close kin.

Even so, there are many variations within these universals and each of the four are regularly broken in individual cases within societies. How the family unit is defined and how it functions vary. In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household. In these cultures, young adults will continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household, or they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead. In Canada, by contrast, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit consisting of parents and their offspring.

Anthropologist George Murdock (1897-1985) first recognized the existence of cultural universals while studying systems of kinship around the world. As a structural functionalist, Murdock found that cultural universals often revolve around the functional requisites all societies need to satisfy to ensure human survival, such as finding food, clothing, and shelter. They also form around universally shared human experiences, such as birth and death, or illness and healing. Through his research, Murdock identified other universals including language, the concept of personal names, and, interestingly, jokes. Humour seems to be a universal way to release tensions and create a sense of unity among people (Murdock, 1949). Sociologists consider humour necessary to human interaction because it helps individuals navigate otherwise tense situations.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Is Music a Cultural Universal?

Imagine an audience sitting in a theatre, watching a film. The movie opens with the hero sitting on a park bench with a grim expression on her face. Cue the music. The first slow and mournful notes are played in a minor key. As the melody continues, the hero turns her head and sees a man walking toward her. The music slowly gets louder, and the dissonance of the chords sends a prickle of fear running down the audience’s spine. They sense that she is in danger.

Now imagine that the audience is watching the same movie, but with a different soundtrack. As the scene opens, the music is soft and soothing with a hint of sadness. They see the hero sitting on the park bench and sense her loneliness. Suddenly, the music swells. The woman looks up and sees a man walking toward her. The music grows fuller, and the pace picks up. The audience feels their hearts rise in their chests. This is a happy moment.

Music has the ability to evoke emotional responses. In television shows, movies, and even commercials, music elicits laughter, sadness, or fear. Are these types of musical cues cultural universals? Henry Wadsworth Longfellow declared in 1835 that “‘music is the universal language of mankind” (Longfellow, 1835). Is music a universal language?

This is a matter of debate. From the perspective of sociobiology or evolutionary psychology, if music is universal then it must have a basis in the genetics of the human species. Ethnomusicologists point out, however, that even though music is widespread cross-culturally, the meanings, uses, behavioural functions and forms of music vary so widely as to be difficult to tie to any specific biological mechanism, adaptive function, or reproductive advantage.

On the other hand, the Harvard Data Science Initiative conducted a comprehensive examination of every culture in the ethnographic record, 5000 detailed descriptions of song performances, and a random sample of field recordings (Mehr et al., 2019). They determined that music is universal, occurring in every society observed. Moreover, while music did vary between cultures, it varied along three variables of social context that were common to all cultures (degree of formality, degree of arousal, and degree of religiosity) and was associated with common behavioural contexts shared by all cultures such as lullabies, healing practices, dance and love.

To understand what exactly is universal about music, they proposed that while a fixed biological response could not account for the cross-cultural variability in musical expression, the variability concealed regularities emerging from common underlying psychological mechanisms. Songs with similar behavioural functions in different societies, like infant care and healing, tended to have similar musical features (accent, tempo, pitch range, etc.). A lullaby or healing song in one culture was very similar to a lullaby or healing song in another culture. All cultures put words to their songs, all cultures danced to songs, all songs had tonal centers, and all melodies and rythyms found balance between monotony and chaos (Mehr et al., 2019).

Similarly, in 2009, a team of psychologists, led by Thomas Fritz of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, studied people’s reactions to music they had never heard (Fritz et al., 2009). The research team traveled to Cameroon, Africa, and asked Mafa tribal members to listen to Western music and compared their reactions to Canadian interpretations of the same music. The tribe, isolated from Western culture, had never been exposed to Western culture and had no context or experience within which to interpret its music. Even so, as the tribal members listened to a Western piano piece, they were able to recognize three basic emotions: happiness, sadness, and fear. They rated the music as happy, sad and fearful similarly to Canadian listeners. Music, it turns out, is a sort of universal language.

Researchers also found that music can foster a sense of wholeness within a group. In fact, scientists who study the evolution of language have concluded that originally language (an established component of group identity) and music were one (Darwin, 1871). Additionally, since music is largely nonverbal, the sounds of music can cross societal boundaries more easily than words. Music allows people to make connections where language might be a more difficult barricade. As Fritz and his team found, music and the emotions it conveys can be cultural universals.

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

Despite how much humans have in common, cultural differences are far more prevalent than cultural universals. For example, while all cultures have language, analysis of particular language structures and conversational etiquette reveals tremendous differences. In some Middle Eastern cultures, it is common to stand close to others in conversation. North Americans keep more distance, maintaining a large personal space. Even something as simple as eating and drinking varies greatly from culture to culture. If a professor comes into an early morning class holding a mug of liquid, what do students assume she is drinking? In Canada, it is most likely filled with coffee, not black tea, a favourite in England, or yak butter tea, a staple in Tibet.

The way cuisines vary across cultures fascinates many people. Some travelers, like celebrated food writer Anthony Bourdain, pride themselves on their willingness to try unfamiliar foods, while others return home expressing gratitude for their native culture’s fare. Canadians might express disgust at other cultures’ cuisine, thinking it is gross to eat meat from a dog or guinea pig for example, while they do not question their own habit of eating cows or pigs. Such attitudes are an example of ethnocentrism, or evaluating and judging another culture based on how it compares to one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism, as sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) described the term, involves a belief or attitude that one’s own culture is better than all others (1906). Almost everyone is a little bit ethnocentric. For example, Canadians tend to say that people from England drive on the “wrong” side of the road, rather than the “other” side. Someone from a country where dogs are considered dirty and unhygienic might find it off-putting to see a dog in a French restaurant.

A high level of appreciation for one’s own culture can be healthy; a shared sense of community pride, for example, connects people in a society. But ethnocentrism can lead to disdain or dislike for other cultures, causing misunderstanding and conflict. This is even more significant when ethnocentrism works its way into social scientific perspectives and public policy decision making. Social scientists with the best intentions sometimes travel to another society to “help” its people, seeing them as uneducated or backward, essentially inferior. In reality, these scientists are guilty of cultural imperialism — the deliberate imposition of one’s own cultural values on another culture.

Europe’s colonial expansion, begun in the 16th century, was often accompanied by a severe cultural imperialism. European colonizers often viewed the people in the lands they colonized as uncultured savages who were in need of European governance, dress, religion, and other cultural practices. On the Northwest coast of Canada, the various First Nations’ potlatch (gift-giving) ceremony was made illegal in 1885 because it was thought to prevent Indigenous peoples from acquiring the proper industriousness and respect for material goods required by civilization. A more modern example of cultural imperialism was the Green Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s in which international aid agencies introduced technologically intensive agricultural methods and hybrid crop strains from developed countries to improve agricultural output in Mexico, India, the Philippines, and Africa, while overlooking indigenous varieties and agricultural approaches that were better suited to the particular region.

Ethnocentrism can be so strong that when confronted with all the differences of a new culture, one may experience disorientation and frustration. Sociologists call this culture shock. A traveler from B.C. might find the established “center of Canada” urban culture of Toronto restrictive. An exchange student from China might be annoyed by the constant interruptions in class as other students ask questions — a practice that can be considered rude in China. Perhaps the B.C. traveler was initially captivated with Toronto’s centrality to intellectual and cultural life in Canada, and the Chinese student was originally excited to see a Canadian-style classroom firsthand. But as they experience unanticipated differences from their own culture, their excitement gives way to discomfort and doubts about how to behave appropriately in the new situation. Eventually, as people learn more about a culture, they recover from culture shock.

Culture shock can occur when people do not expect to find cultural differences. Anthropologist Ken Barger (1971) discovered this when conducting participatory observation in an Inuit community in the Canadian Arctic. Originally from Indiana, Barger hesitated when invited to join a local snowshoe race. He knew he would never hold his own against these experts. Sure enough, he finished last, to his mortification. But the tribal members congratulated him, saying, “You really tried!” In Barger’s own culture, he had learned to value victory. it was not worth participating if there was no chance of winning. To the Inuit people winning was enjoyable, but their culture valued survival skills essential to their environment: How hard someone tried could mean the difference between life and death. Over the course of his stay, Barger participated in caribou hunts, learned how to take shelter in winter storms, and sometimes went days with little or no food to share among tribal members. Trying hard and working together, two nonmaterial values, were indeed much more important than winning.

During his time with the Inuit, Barger learned to engage in cultural relativism. Cultural relativism is the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards rather than viewing it through the lens of one’s own culture. The anthropologist Ruth Benedict (1887-1948) argued that each culture has an internally consistent pattern of thought and action, which alone could be the basis for judging the merits and morality of the culture’s practices. In sociological research, cultural relativism requires an open mind and a willingness to consider new values and norms. Insight into unfamiliar sociological phenomena requires the abandonment of preconceptions and prejudgements.

The logic of cultural relativism is at the basis of contemporary policies of multiculturalism. However, indiscriminately embracing everything about a new culture is not always possible. Even the most culturally relativist people from egalitarian societies, such as Canada — societies in which women have political rights and control over their own bodies — would question whether the widespread practice of female genital circumcision in countries such as Ethiopia and Sudan should be accepted just because it has been a part of a cultural tradition.

Sociologists attempting to engage in cultural relativism may struggle to reconcile aspects of their own culture with aspects of a culture they are studying. Pride in one’s own culture does not have to lead to imposing its values on others or using them to evaluate another culture’s practices; A great deal of important information and insight can be overlooked or missed in this way. But nor does an appreciation for another culture preclude individuals from studying it with a critical eye. In the case of female genital circumcision, a universal right to life and liberty of the person conflicts with the neutral stance of cultural relativism. It is not necessarily ethnocentric to be critical of practices that violate universal standards of human dignity because these standards are cultural universals, contained in the cultural codes of all cultures, (even if they are not necessarily followed in practice). Not every practice can be regarded as culturally relative. Cultural traditions are not immune from power imbalances, disagreements, and emancipatory movements that seek to correct them. Research on female genital mutilation (FGM), for example, shows that when practicing communities themselves decide to abandon FGM, the practice can be eliminated very rapidly (WHO, 2020).

Feminist sociology is particularly attuned to the way that most cultures present a male-dominated view of the world as if it were simply the view of the world. Androcentrism is a perspective in which male concerns, male attitudes, and male practices are presented as “normal” or define what is significant and valued in a culture. Women’s experiences, activities, and contributions to society and history are ignored, devalued, or marginalized.

As a result the perspectives, concerns, and interests of only one sex and class are represented as general. Only one sex and class are directly and actively involved in producing, debating, and developing its ideas, in creating its art, in forming its medical and psychological conceptions, in framing its laws, its political principles, its educational values and objectives. Thus a one-sided standpoint comes to be seen as natural, obvious, and general, and a one-sided set of interests preoccupy intellectual and creative work (Smith, 1987).

In part, this is simply a question of the bias of those who have the power to define cultural values, and in part, it is the result of a process in which women have been actively excluded from the culture-creating process. It is still common, for example, to read writing that uses the personal pronoun “he” or the word “man” to represent people in general or humanity as a whole. The overall effect is to establish masculine values and imagery as normal. A “policeman” brings to mind a man who is doing a “man’s job,” when in fact, women have been involved in policing for several decades now.

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Multiculturalism in Canada

One prominent aspect of contemporary Canadian cultural identity is the idea of multiculturalism. Canada was the first officially declared multicultural society in which, as Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau declared in 1971, no culture would take precedence over any other. As he put it, “What could be more absurd than the concept of an ‘all-Canadian’ boy or girl?” (Trudeau cited in Graham,1998). Multiculturalism refers to both the existence of a diversity of cultures within one territory, and to a way of conceptualizing and managing cultural diversity through social policy. As a policy, multiculturalism seeks to both promote and recognize cultural differences while addressing the inevitability of cultural tensions. In the 1988 Multiculturalism Act, the federal government officially acknowledged its role “in bringing about equal access and participation for all Canadians in the economic, social, cultural, and political life of the nation” (Government of Canada, as cited in Angelini & Broderick, 2012).

However, the focus on multiculturalism and culture per se has not always been so central to Canadian public discourse. Multiculturalism represents a relatively recent cultural development. Prior to the end of World War II, Canadian authorities used the concept of biological race to differentiate the various types of immigrants and Indigenous peoples in Canada. This focus on biology led to corresponding fears about the quality of immigrant “stock” and the problems of how to manage the mixture of races. In this context, three different models for how to manage diversity were in contention: (1) the American “melting pot” paradigm in which the mingling of races was thought to be able to produce a super race with the best qualities of all races intermingled, (2) strict exclusion or deportation of races seen to be “unsuited” to Canadian social and environmental conditions, or (3) the Canadian “mosaic” that advocated for the separation and compartmentalization of races (Day, 2000).

After World War II, the category of race was replaced by culture and ethnicity in the public discourse, but the mosaic model was retained. Culture came to be understood in terms of the new anthropological definitions of culture as a deep-seated emotional-psychological phenomenon essential to social well-being and belonging. In this conceptualization, to be deprived of culture through coercive assimilation would be a type of cultural genocide. As a result, alternatives to cultural assimilation into the dominant Anglo-Saxon culture were debated, and the Canadian mosaic model for managing a diverse population was redefined as multiculturalism. Based on a new appreciation of the importance of culture, and with increased immigration from non-European countries, Canadian identity was re-imagined in the 1960s and 1970s as a happy cohabitation of cultures, each of which was encouraged to maintain their cultural distinctiveness. So while the cultural identities of Canadians are diverse, the cultural paradigm in which their coexistence is conceptualized — multiculturalism — has come to be equated with Canadian cultural identity.

However, these developments have not alleviated the problems of cultural difference with which sociologists are concerned. Multicultural policy has sparked numerous, remarkably contentious issues ranging from whether Sikh RCMP officers can wear turbans to whether Mormon sects can have legal polygamous marriages. In 2014, the Parti Québécois in Quebec proposed a controversial Charter of Quebec Values that would, to reinforce the neutrality of the state, ban public employees from wearing “overt and conspicuous” religious symbols and headgear. In 2019, the Quebec ban on religious symbols was enacted by governing Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) Party as Bill 21. This position represented a unique Quebec-based concept of multiculturalism known as interculturalism. Whereas multiculturalism begins with the premise that there is no dominant culture in Canada, interculturalism begins with the premise that in Quebec, francophone culture is dominant but also precarious in the North American context. It cannot risk further fragmentation. Therefore the intercultural model of managing diversity is to recognize and respect the diversity of immigrants who seek to integrate into Quebec society but also to make clear to immigrants that they must recognize and respect Quebec’s common or “fundamental” values.

Critics of multiculturalism identify four related problems:

- Multiculturalism only superficially accepts the equality of all cultures while continuing to limit and prohibit actual equality, participation, and cultural expression. One key element of this criticism is that there are only two official languages in Canada — English and French — which limits the full participation of non-anglophone/francophone groups.

- Multiculturalism obliges minority individuals to assume the limited cultural identities of their ethnic group of origin, which leads to stereotyping minority groups, ghettoization, and feeling isolated from the national culture.

- Multiculturalism causes fragmentation and disunity in Canadian society. Minorities do not integrate into existing Canadian society but demand that Canadians adopt or accommodate their way of life, even when they espouse controversial values, laws, and customs (like polygamy or Sharia Law).

- Multiculturalism is based on recognizing group rights which undermines constitutional protections of individual rights.

On the other hand, proponents of multiculturalism like Will Kymlicka (2012) describe the Canadian experience with multiculturalism as a success story. Kymlicka argues that the evidence shows:

Immigrants in Canada are more likely to become citizens, to vote and to run for office, and to be elected to office than immigrants in other Western democracies, in part because voters in Canada do not discriminate against such candidates. Compared to their counterparts in other Western democracies, the children of immigrants have better educational outcomes, and while immigrants in all Western societies suffer from an “ethnic penalty” in translating their skills into jobs, the size of this ethnic penalty is lowest in Canada. Compared to residents of other Western democracies, Canadians are more likely to say that immigration is beneficial and less likely to have prejudiced views of Muslims. And whereas ethnic diversity has been shown to erode levels of trust and social capital in other countries, there appears to be a “Canadian exceptionalism” in this regard (Kymlicka, 2012).

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.5 Queen Elizabeth’s Waving Hand Dolls, Windsor, England by Alex-David Baldi, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.6 Tokyo 1045 by Tokyoform is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.7 Chiropracter Man by Jenni C. is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.8 Violence! [Explored] by Riccardo Cuppini, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.9 The Baby Smile by llee_wu, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.10 Francis Galton 1850s, author not stated (scanned from Karl Pearson’s The Life, Letters, and Labors of Francis Galton), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 3.11 Gene by National Human Genome Research Institute, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 3.12 Angelina Jolie Cannes 2013 by Georges Biard, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.

- Figure 3.13 Queenscliff Music Festival, 2013 by Tony Proudfoot, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.14 Ruth Benedict, 1937, by World Telegram Staff photographer, Library of Congress, ID: cph.3c14649, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection (through instrument of gift), via Wikimedia Commons. No copyright restriction known. Public Domain.

- Figure 3.15 Multiculturalism tree planted in Stanley Park by Province of British Columbia, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.