Chapter 5. Socialization

5.1. Theories of Self Development

Danielle’s case underlines an important point that sociologists make about socialization, namely that the human self does not emerge “naturally” as a process driven by biological mechanisms. What is a self? What does it mean to have a self?

The self refers to a person’s distinct sense of identity. It is who a person is for themselves and who they are for others. It has consistency and continuity through time, and an internal coherence that distinguishes people as unique persons. However, there is always something precarious and incomplete about the self. Selves change through the different stages of life. Sometimes they do not measure up to the ideals people hold for themselves or others, and sometimes they can be wounded by people’s interactions with others or thrown into crisis. As Zygmunt Bauman (2004) puts it, one’s distinct sense of identity is a projection or a “postulated self,” a “horizon towards which I strive and by which I assess, censure and correct my moves.” It is not only what a person has done in their lives, but how they imagine themselves to be. Clearly, the self does not develop in the absence of socialization. For sociologists, the self is a social product.

The American sociologist George Herbert Mead is often seen as the founder of the school of symbolic interactionism in sociology, although he referred to himself as a social behaviourist. His conceptualization of the self has been very influential. Mead (1934) defines the emergence of the self as a thoroughly social process: “The self, as that which can be an object to itself, is essentially a social structure, and it arises in social experience.” In what sense is the self a “social structure”?

The key quality of the self that Mead is concerned with is its ability to be reflexive or self-aware (i.e., to be an “object” to oneself). One can think about oneself, or feel how one is feeling. This key quality of the self can only arise in a social context through social interactions with others. In Charles Horton Cooley’s (1902) concept of the “looking glass self,” others, and their attitudes towards the self, are like mirrors in which the self is able to see itself and formulate an idea of who they are. Without others, or without society, the self could not exist: “[I]t is impossible to conceive of a self arising outside of social experience” (Mead, 1934, p. 293).

Even when the self is alone for extended periods of time (hermits, prisoners in isolation, etc.), an internal conversation goes on that would not be possible if the individual had not been socialized already. The examples of feral children like Victor of Aveyron or children like Danielle who have been raised under conditions of extreme social deprivation attest to the difficulties these individuals confront when trying to develop this reflexive quality of humanity. They often cannot use language, form intimate relationships, or play games. Socialization is not simply the process through which people learn the norms and rules of a society; it is also the process by which people become aware of themselves as they interact with others. It is the process through which people are able to become people in the first place.

The necessity for early social contact was demonstrated by the research of Harry and Margaret Harlow. From 1957–1963, the Harlows conducted a series of experiments studying how rhesus monkeys, who behave a lot like people, are affected by isolation as babies. They studied monkeys raised under two types of “substitute” mothering circumstances: a mesh and wire sculpture, or a soft terry cloth “mother.” The monkeys systematically preferred the company of a soft, terry cloth substitute mother (closely resembling a rhesus monkey) that was unable to feed them, to a mesh and wire mother that provided sustenance via a feeding tube. This demonstrated that while food was important, social comfort was of greater value (Harlow & Harlow, 1962; Harlow, 1971). Later experiments testing more severe isolation revealed that such deprivation of social contact led to significant developmental and social challenges later in life.

Theories of Self Development

When a person is born, they have a genetic makeup and biological traits. However, who they are as human beings develops through social interaction. Many scholars, in both psychology and sociology, have described the process of self development as a means of understanding how that “self” becomes socialized through progressive stages.

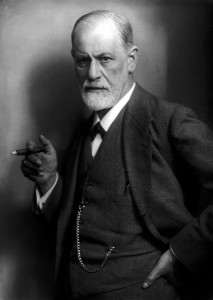

Sigmund Freud

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was one of the most influential modern scientists to put forth a theory about how people develop a sense of self. He believed personality and sexual development were closely linked, and divided the maturation process into universal psychosexual stages: oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital. Each stage involves the child’s discovery and passage through the bodily pleasures linked to breastfeeding, toilet training, and sexual awareness (Freud, 1905).

Key to Freud’s approach to child development was his emphasis on tracing the formations of desire and pleasure in a child’s life. The child is at the centre of a tricky negotiation between internal, pleasure-oriented drives for gratification or wish fulfillment (the pleasure principle) and external, social demands that the child repress those drives to conform to the rules and regulations of civilization (the reality principle). Failure to resolve the traumatic tensions and impasses of childhood psychosexual development causes emotional and psychological consequences throughout adulthood. For example, according to Freud, the failure of a child to properly engage in or disengage from a specific stage of development results in predictable outcomes later in life in the form of neuroses, fixations, and psychological distress. An adult with an oral fixation may indulge in overeating or binge drinking. An anal fixation may produce a neat freak (hence the term “anal retentive”), while a person stuck in the phallic stage may be promiscuous or emotionally immature.

Psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–1994) created a theory of personality development based on the work of Freud. However, Erikson (1963) was more interested in the social and cultural dimensions of Freud’s child development schema. Following Freud, he noted that each stage of psychosexual child development was associated with the formation of basic emotional structures in adulthood. The outcome of the oral stage will determine whether someone is trustful or distrustful as an adult; the outcome of the anal stage, whether they will be confident and generous or ashamed and doubtful; the outcome of the genital stage, whether they will be full of initiative or guilt.

Erikson retained Freud’s idea that the stages of child development were universal, but he believed that different cultures handled them differently. Child-raising techniques varied in line with the dominant social formation of their societies. So, for example, the tradition in the communally-based Sioux First Nation was not to wean infants but to breastfeed until the infant lost interest. This tradition created trust between the infant and their mother, and eventually trust between the child and the tribal group as a whole. On the other hand, modern industrial societies practice early weaning of children, which leads to a more distrustful character structure. Children develop a possessive disposition toward objects that carries with them through to adulthood. The result of early weaning is that the child is eager to get things and grab hold of things in lieu of the experience of generosity and comfort in being held.

Societies like the Sioux, in which individuals rely heavily on each other and on the group to survive in a hostile environment, will handle child training in a different manner and with different outcomes than societies based on individualism, competition, self-reliance, and self-control (Erikson, 1963).

Making Connections: Sociological Concepts

Sociology or Psychology: What’s the Difference?

If sociologists and psychologists are both interested in people and their behaviour, how are these two disciplines different? What do they agree on, and where do their ideas diverge? The answers are complicated, but the distinction is important to scholars in both fields.While both disciplines are interested in human behaviour, psychologists are focused on how the mind influences that behaviour, while sociologists study the role of society in shaping both behaviour and the mind. Psychologists are interested in people’s mental development and how their minds process their world and influence their actions. Sociologists are more likely to focus on how different aspects of social life structure an individual’s relationship with the world. Another way to think of the difference is that psychologists tend to look inward at qualities of individuals’ internal life (mental health, emotional processes, cognitive processing), while sociologists tend to look outward to qualities of individuals’ social context (social institutions, cultural norms, interactions with others) to understand human behaviour.As described in Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology, Émile Durkheim (1958–1917) was one of the first to emphasize this distinction in sociological research, when he attributed differences in suicide rates among people to social causes (degree of social integration) rather than to psychological causes (psychopathology, mental health) (Durkheim, 1897). This same approach applies today. For example, a sociologist studying how a couple gets to the point of their first kiss on a date might focus the research on cultural norms of dating, social patterns of romantic activity in history, or the influence of social background on romantic partner selection. How is this process different for seniors than for teens, for example? A psychologist would more likely be interested in the person’s romantic history, psychological type, or the mental processing of erotic desire.The point that sociologists like Durkheim would make is that an analysis of individuals at the psychological level cannot adequately account for social variability of behaviours. The difference in suicide rates of Catholics and Protestants, or the difference in dating scripts across cultures or historical periods, can not be explained at the level of individual psychology. Sometimes sociology and psychology can combine in interesting ways, however. Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism (1979) argued that the neurotic personality was a product of an earlier Protestant ethic style of competitive capitalism; whereas, late postindustrial consumer capitalism is conducive to narcissistic personality structures (the “me” society). Theodore Adorno and his colleagues described the features of an authoritarian personality that was susceptible to the appeals of fascistic political formations (Adorno et al., 1950). More recently the “dark triad” personality traits — narcissism (entitled self-importance), Machiavellianism (strategic exploitation and deceit), and psychopathy (callousness and cynicism) — have been shown to predict white nationalist (“alt-right”) political beliefs and behaviours (Moss & O’Connor, 2020).

Charles Horton Cooley

One of the pioneering contributors to sociological perspectives on self-development was the American sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929). Cooley asserted that people’s self understanding is constructed, in part, by their perception of how others view them — a process termed “the looking glass self” (Cooley, 1902).According to Cooley, people base their self-image on what they think other people see. People imagine or project how they must appear to others, then react to this speculation. They don certain clothes, prepare their hair in a particular manner, wear makeup, use cologne, and the like — all with the notion that their presentation of themselves is going to affect how others perceive them. They anticipate a certain reaction, and, if lucky, they get the one they desire and feel good about it.Cooley believed that the sense of self is not based on an internal source of individuality therefore. Rather, people imagine how they look to others, draw conclusions based on others’ reactions, and then develop their personal sense of self. In other words, other people’s reactions are like a mirror in which the self is reflected. People live a mirror image of themselves. As he put it, “The imaginations people have of one another are the solid facts of society” (Cooley, 1902).The self or “self idea” is thoroughly social. It is not an expression of the internal essence of the individual, or of the individual’s unique psychology which emerges as the individual matures. It is based on how people imagine they appear to others. It is not how the self actually appear to others but the self’s projection of what others think or feel towards it. This projection defines how people feel about themselves and who they feel themselves to be. The development of a self, therefore, involves three elements in Cooley’s analysis: “the imagination of our appearance to the other person; the imagination of his judgement of that appearance, and some sort of self-feeling, such as pride or mortification” (Cooley, 1902).

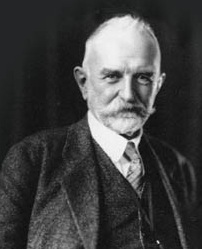

George Herbert Mead

Later, George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) advanced a more detailed sociological approach to the self. He agreed that the self, as a person’s distinct identity, is only developed through social interaction. As noted above, he argued that the defining component of the self is its capacity for self reflection, its capacity to be “an object to itself” (Mead, 1934). Somebody locks their keys in the car and thinks, “What a dummy I am!” Or, somebody thinks to themselves, “I’m tired but I’m going make myself stay up and finish this assignment before I go to bed.”Addressing oneself in this manner are examples of “being an object to oneself.”

Mead broke the self-reflective self down into two components or “phases:” the “I” and the “me.” The “me” represents the part of the self in which one recognizes the “organized sets of attitudes” of others toward the self. It is who the self is in others’ eyes: a social role, a “personality,” or a public persona. The “I,” on the other hand, represents the part of the self that acts on its own initiative or responds to the organized attitudes and expectations of others. It is the novel, spontaneous, unpredictable part of the self: the part of the self that embodies the possibility of change or undetermined action. The self is always caught up in a social process in which it flips back and forth between two distinguishable phases: the I and the me, the reflexive self and the self as social ‘object.’ In acting, the self oscillates between its own individual responses to various social situations and the attitudes of the community.

This flipping back and forth is the condition of the human ability to be social. It is not an ability that humans are born with (Mead, 1934). The case of Danielle, for example, illustrates what happens when social interaction is absent from early experience: She had no ability to see herself as others would see her. From Mead’s point of view, she had no “self.” Without others, or without society, the reflexive self cannot exist. As Mead put it, “[I]t is impossible to conceive of a self arising outside of social experience” (Mead, 1934).

How does one get from being a newborn to being a human with a “self”? In Mead’s theory of childhood development, the child develops through stages in which the child’s increasing ability to play social roles attests to their increasing solidification of a social sense of self. It is interesting here to contrast Mead’s sociological model of child development, which emphasizes the progressive ability to grasp and participate in social interaction, with psychological models, like Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s, which emphasize stages of psychological or cognitive capacity. For Mead, learning how to play social roles — the set of behaviours expected of a person who occupies a particular social status or position in society — requires learning how to put oneself in the place of another, to see through another’s eyes. At one point in their life, a child simply cannot play a game like baseball; they do not “get it” because they cannot insert themselves into the complex role of the player. They cannot see themselves from the point of view of all the other players on the field or figure out their place within a rule bound sequence of activities. At another point in their life, a child becomes able to learn how to play. Mead developed a specifically sociological theory of the path of development that all people go through by focusing on the developing capacity to put oneself in the place of another, or role play: the four stages of child socialization.

Four Stages of Child Socialization

During the preparatory stage, children are only capable of imitation: They have no ability to imagine how others see things. They copy the actions of people with whom they regularly interact, such as their mothers and fathers. A child’s baby talk is a reflection of its inability to make an object of themselves. The separation of I and me does not yet exist in an organized manner to enable the child to relate to themselves.

This is followed by the play stage, during which children begin to imitate and take on roles that another person might have. Thus, children might try on a parent’s point of view by acting out “grownup” behaviour, like playing dress up and acting out the mom role, or talking on a toy cell phone the way they see their father do.

He plays that he is, for instance, offering himself something, and he buys it; he gives a letter to himself and takes it away; he addresses himself as a parent, as a teacher; he arrests himself as a policeman…. The child says something in one character and responds in another character, and then his responding in another character is a stimulus to himself in the first character, and so the conversation goes on (Mead, 1934).

However, children are still not able to take on roles in a consistent and coherent manner. Role play is very fluid and transitory in this stage, and children flip in and out of roles easily. They “pass[..] from one role to another just as a whim takes [them]” (Mead, 1934).

During the game stage, children learn to consider several specific roles at the same time and how those roles interact with each other. They learn to understand interactions involving different people with a variety of purposes. They understand that role play in each situation involves responding to other people’s cues and following a consistent set of rules and expectations. For example, a child at this stage is likely to be aware of how their own behaviour in a restaurant is linked to, and constrained by, the different responsibilities of the other people there: someone seats them, another takes their order, someone else cooks the food, another person clears away dirty dishes, other diners (mostly) mind their own business, mom or dad pays the bill, etc. A smooth dining experience depends on the “good behaviour” of everyone playing their role.

Mead uses the example of a baseball game. “If we contrast play [i.e., the play stage] with the situation in an organized game, we note the essential difference that the child who plays in a game must be ready to take the attitude of everyone else involved in that game, and that these different roles must have a definite relationship to each other” (Mead, 1934). At one point in learning to play baseball, children do not understand that when they hit the ball they need to run, or that after their turn someone else gets a turn to bat. In order for baseball to work, the players not only have to know what the rules of the game are, and what their specific role in the game is (batter, catcher, first base, etc.), but know simultaneously the role of every other player on the field. They have to see the game from the perspective of others. “What he does is controlled by his being everyone else on that team, at least in so far as those attitudes affect his own particular response” (Mead, 1934). The players have to be able to anticipate the actions of others and adjust or orient their behaviour accordingly. Role play in games like baseball involves the understanding that ones own role is tied to the roles of several people simultaneously and that these roles are governed by fixed, or at least mutually recognized, rules and expectations.

Finally, children develop, understand, and learn the idea of the generalized other, the common behavioural expectations of general society. The generalized other is no one in particular, but a composite of “society’s” perspective. By this stage of development, an individual is able to internalize how they are viewed, not simply from the perspective of several particular others (like in a baseball game), but from the perspective of the generalized other or “organized community.” What would “the community” think if I did this or that? Being able to guide one’s actions according to the attitudes of the generalized other provides the basis of having a stable “self” in the sociological sense. “[O]nly in so far as he takes the attitudes of the organized social group to which he belongs toward the organized, cooperative social activity or set of such activities in which that group as such is engaged, does he develop a complete self” (Mead, 1934).

This capacity to see the self through the eyes of the generalized other defines the conditions of thinking, of language use, and of society itself as the organization of complex co-operative processes and activities.

It is in the form of the generalized other that the social process influences the behavior of the individuals involved in it and carrying it on, that is, that the community exercises control over the conduct of its individual members; for it is in this form that the social process or community enters as a determining factor into the individual’s thinking. In abstract thought the individual takes the attitude of the generalized other toward himself, without reference to its expression in any particular other individuals; and in concrete thought he takes that attitude in so far as it is expressed in the attitudes toward his behavior of those other individuals with whom he is involved in the given social situation or act. But only by taking the attitude of the generalized other toward himself, in one or another of these ways, can he think at all; for only thus can thinking — or the internalized conversation of gestures which constitutes thinking — occur. And only through the taking by individuals of the attitude or attitudes of the generalized other toward themselves is the existence of a universe of discourse, as that system of common or social meanings which thinking presupposes at its context, rendered possible (Mead, 1934).

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development and Gilligan’s Theory of Gender Differences

Moral development is an important part of the socialization process. The term refers to the way people learn what society considers to be “good” and “bad,” which is important for a smoothly functioning society. Moral development prevents people from acting on unchecked urges, instead considering what is right for society and good for others. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) was interested in how people learn to decide what is right and what is wrong. To understand this topic, he developed a theory of moral development that includes three levels: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.

In the preconventional stage, young children, who lack a higher level of cognitive ability, experience the world around them only through their senses. It is not until the teen years that the conventional stage develops, when youngsters become increasingly aware of others’ feelings and take those into consideration when determining what is good and bad. The final stage, called postconventional, is when people begin to think of morality in abstract terms, such as North Americans believing that everyone has equal rights and freedoms. At this stage, people also recognize that legality and morality do not always match up evenly (Kohlberg, 1981). When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians turned out in 2011 to protest government autocracy, they were using postconventional morality. They understood that although their government was legal, it was not morally correct.

Carol Gilligan (b. 1936), recognized that Kohlberg’s theory might show gender bias since his research was conducted only on male subjects. Would female study subjects have responded differently? Would a female social scientist notice different patterns when analyzing the research? To answer the first question, she set out to study differences between how boys and girls developed morality. Gilligan’s research demonstrated that boys and girls do, in fact, have different understandings of morality. Boys tend to have a justice perspective, placing emphasis on rules, laws, and individual rights. They learn to morally view the world in terms of categorization and separation. Girls, on the other hand, have a care and responsibility perspective; they are concerned with responsibilities to others and consider people’s reasons behind behaviour that seems morally wrong. They learn to morally view the world in terms of connectedness.

Gilligan also recognized that Kohlberg’s theory rested on the assumption that the justice perspective was the right, or better, perspective. Gilligan, in contrast, theorized that neither perspective was “better”: The two norms of justice served different purposes. Ultimately, she explained that boys are socialized for a work environment where rules make operations run smoothly, while girls are socialized for a home environment where flexibility and empathy allow for harmony in caretaking and nurturing (Gilligan, 1982, 1990).

The Socialization of Gender

How do girls and boys learn different gender roles? Gender differences in the ways boys and girls play and interact develop from a very early age, sometimes despite the efforts of parents to raise them in a gender neutral way. Little boys seem inevitably to enjoy running around playing with guns and projectiles, while little girls like to study the effects of different costumes on toy dolls. Peggy Orenstein (2012) describes how her two-year-old daughter happily wore her engineer outfit and took her Thomas the Tank Engine lunchbox to the first day of preschool. It only took one little boy to say to her that “girls don’t like trains!” for her to ditch Thomas and move on to more gender “appropriate” concerns like princesses. If gender preferences are not inborn or biologically hard-wired, how do sociologists explain them?

As the Thomas the Tank Engine example suggests, doing gender — performing tasks based upon the gender assigned by society — is learned through interaction with others in much the same way that Mead and Cooley described for socialization in general. Children learn how to do gender through direct feedback from others, particularly when they are censured for violating gender norms. Gender is in this sense a social performance and an accomplishment rather than an innate trait (West and Zimmerman, 1987). If a child successfully performs an activity like a boy or a girl “should,” they are accepted or rewarded, but if they fail, they are often corrected or get disapproving feedback. Doing gender therefore takes place through the child’s developing awareness of self through their interaction with others. In the Freudian model of gender development, children become aware of their own genitals, and spontaneously generate erotic fantasies and speculations whose resolution leads them to identify with their mother or father. Whereas in the sociological model, it is adults’ awareness of, and gendered interpretation of the meaning of, a child’s genitals that leads to gender labeling and reinforcement of gender roles.

West and Zimmerman (1987) emphasize that doing gender, whether as children or adults, involves ongoing, routinized work to present a credible and accepted performance. This is an interactive process that could be discredited if not performed well or unambiguously. Successful displays of endurance, strength, and competitive spirit in sport provide a typical demonstration of masculinity. In contrast, successful displays of courtesy, modesty, and empathy in hosting social gatherings provide a typical demonstration of femininity. It is through these performances that concepts of gender difference are solidified and made to seem like the natural expression of underlying biological differences. Through their repetition, they “cast particular pursuits as expressions of masculine and feminine ‘natures'” (West and Zimmerman, 1987). Learning gender is therefore not so much about being socialized into fixed gender roles established by society. It is learning how to generate or perform acceptable gender performances in different social situations.

A child who learns to do gender therefore learns how to successfully display gender. Cahill (1986) observes that one of the first key social distinctions young children recognize and wish to demonstrate to parents or others is to distinguish themselves from “babies” who are unable to control themselves and require close supervision. But being told to “stop being a baby” subtly reinforces a distinction between two social identities that are routinely available to them: the discredited identity of “being a baby” on one hand or the approved identity of being either a “big boy” or “big girl” on the other.

Subsequently, little boys appropriate the gender ideal of “efficaciousness,” that is, being able to affect the physical and social environment through the exercise of physical strength or appropriate skills. In contrast, little girls learn to value “appearance,” that is, managing themselves as ornamental objects. Both classes of children learn that the recognition and use of sex categorization in interaction are not optional, but mandatory (West and Zimmerman, 1987).

It is not until they recognize that the social expectations of the “generalized other” are often divided and variable that children can go back and undo how they have learned to do gender. Nevertheless, as West and Zimmerman emphasize, this undoing often requires making explanations to others to account for differences in gender performance. Children are often acutely aware of the situations in which such explanations will “go over” and the situations in which they will not.

From a very early age, children develop a gender schema, a rudimentary image of gender differences, that enables them to make decisions about appropriate styles of play and behaviour (Fagot & Leinbach, 1989). By the time children enter kindergarten, they are able to “readily differentiate between masculine and feminine roles” while having a “firm understanding of the types of behaviour ‘deemed appropriate’ for males and females” (Crisp & Hiller, 2011). As they integrate their sense of self into this developing schema, they gradually adopt consistent and stable gender roles. Consistency and stability do not mean that the learned gender roles are permanent, however, as would be suggested by a biological or hard-wired model of gender. Physical expressions of gender, such as “throwing like a girl,” can be transformed into a new stable gender schema when the little girl joins a softball league.

Fagot and Leinbach’s (1986, 1989) research into the development of gender schemata showed that very young children, averaging about two years old, could not correctly classify photographs of adults and children by their gender; whereas, slightly older children, averaging 2.5 years old, could. They concluded that the younger children had not yet developed a gender schema. They also observed that older children who could correctly classify the photos by gender demonstrated gender specific play; they tended to choose same-gender play groups and girls were less aggressive in their play. The older children were integrating their sense of self into their gender schema and behaving accordingly.

Similarly, when they studied children at home, they found that children at age 1.5 years could not assign gender to photographs correctly and did not engage in gender-typed play. However, by age 2.25 years about half of the children could classify the photos and were engaging in gender-specific play. These “early labellers” were distinguished from those who could not classify photos by the way their parents interacted with them. Parents of early adopters were more likely to use differential reinforcement in the form of positive and negative responses to gender-typed toy play.

It is interesting, with respect to the difference between the Freudian and sociological models of gender socialization, that the gender schemata of young children develops with respect to external cultural signs of gender, rather than biological markers of genital differences. Sandra Bem (1989) showed young children photos of either a naked child or a child dressed in boys or girls clothing. The younger children had difficulty classifying the naked photos, but could classify the clothed photos. They did not have an understanding of biological sex constancy — i.e., the ability to determine sex based on anatomy regardless of gender signs — but used cultural signs of gender like clothing or hairstyle to determine gender. Moreover, it was the gender schema, not the recognition of anatomical differences, that first determined their choice of gender-typed toys and gender-typed play groups. Bem (1989) suggested that “children who can label the sexes but do not understand anatomical stability are not yet confident that they will always remain in one gender group.”

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

What a Pretty Little Lady!

“What a cute dress!” “I like the ribbons in your hair.” “Wow, you look so pretty today.” According to Lisa Bloom, author of Think: Straight Talk for Women to Stay Smart in a Dumbed Down World, most people use pleasantries like these when they first meet little girls.“So what?” one might ask. Bloom (2011) asserts that people are too focused on the appearance of young girls, and as a result North American society is socializing them to believe that how they look is of vital importance.

Bloom may be on to something. How often does one tell a little boy how attractive his outfit is, how nice looking his shoes are, or how handsome he looks today? To support her assertions, Bloom cites, as one example, that about 50% of girls ages three to six worry about being fat (Bloom, 2011). She is talking about kindergarteners who are concerned about their body image. Sociologists are acutely interested in this type of gender socialization, where societal expectations of how boys and girls should be — how they should behave, what toys and colours they should like, and how important their attire is — are reinforced. One solution to this type of gender socialization is being experimented with at the Egalia preschool in Sweden, where children develop in a genderless environment. All of the children at Egalia are referred to with neutral terms like “friend” or a gender-neutral pronoun “hen” instead of he or she. Books are chosen that avoid traditional gender roles and gendered characters. Traditional toys are present, but consciously set up side by side so that children can play with whatever toy they want to eliminate any reinforcement of gender expectations. Egalia strives to eliminate any reinforcement of gender expectations by teachers as well as children (Haney, 2011).

Research on Sweden’s gender neutral pre-schools shows that children were more likely than their traditionally educated peers to be interested in playing with unfamiliar other-gender children, and were less likely to use gender stereotypes. They were no less likely to automatically encode other’s genders, however (Schutt’s et al., 2017). It is difficult to know what impact gender neutral education might have in a society that remains gendered outside of school. Bloom suggests people start with simple steps. For example, when introduced to a young girl, ask about her favourite book or what she likes. In short, engage her mind, not her outward appearance (Bloom, 2011).

Image Descriptions

Figure 5.6 long description: Psychology and sociology have some overlap. Sociological Social Psychology (SSP) emphasizes a subject’s location in social order, their socialized roles, and historical social context. Psychological Social Psychology (PSP) emphasizes a subject’s mental processes, dispositions, experiences, and immediate social situation. [Return to Figure 5.6].

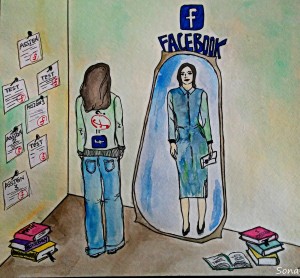

Figure 5.7 long description: A girl wears a sweater and jeans and looks into a mirror. The mirror represents Facebook and shows her reflection wearing a long, professional dress. [Return to Figure 5.7].

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.3 Gollum by Brenda Clarke, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.4 Natural of Love Typical response to cloth mother surrogate in fear test by Harry Harlow, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 5.5 Sigmund Freud, by Max Halberstadt (cropped) by Max Halberstadt, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 5.6 Social-psychology-division by lucidish, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence. (Based on copyright claims.)

- Figure 5.7 Facebook: Self-constructed digital identity and academic performance by Joelle L. via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.8 George Herbert Mead from Moffett Studio/University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center, via Store Norske Leksikon (Large Norwegian Encyclopedia), is in the public domain.

- Figure 5.9 Play at first? by Jay Kleeman, via Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.10 Disney Princess Target Feb 28, 2014 by Mike Mozart, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.11 DSC_8149.JPG by Dave Jacquin, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-ND 2.0 licence.