Chapter 17. Government and Politics

Learning Objectives

- Define and differentiate between government, power, and authority.

- Identify and describe the three types of authority.

17.2 Democratic Will Formation

- Explain the significance of the difference between direct democracy and representative democracy.

- Describe the dynamic of political demand and political supply in determining the democratic “will of the people.”

17.3 The De-Centring of the State: Terrorism, War, Empire, and Political Exceptionalism

- Identify and describe factors of political exception that affect contemporary political life.

17.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Government and Power

- Understand how functionalists, critical sociologists, and symbolic interactionists view government and politics.

Introduction to Government and Politics

In one of Max Weber’s last public lectures — “Politics as a Vocation” (1919) — he asked, what is the meaning of political action in the context of a whole way of life? (More accurately, he used the term Lebensführung: what is the meaning of political action in the context of a whole conduct of life, a theme the chapter returns to in the next section). He asked, what is actually political about political action and what is the place of political action in the ongoing conduct of social life?

Until recently students of political sociology might have been satisfied with an answer that examined how various political institutions and processes function in society: the state, the government, the civil service, the courts, the democratic process, etc. However, in the 21st century, among many other examples sociologists could cite, the events of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, and Bahrain (2010–2012) put seemingly stable political institutions and processes into question. Through the collective action of ordinary citizens, the long-lasting authoritarian regimes of Ben Ali, Gadhafi, Mubarak, and Saleh were brought to an end through what some called “revolution.” Not only did the political institutions all of a sudden not function as they had for decades, [but] they were also shown not to be at the center of political action at all. What do sociologists learn about the place of politics in social life from these examples?

Revolutions are often presented as monumental, foundational political events that happen only rarely and historically: the American revolution (1776), the French revolution (1789), the Russian revolution (1917), the Chinese revolution (1949), the Cuban revolution (1959), the Iranian revolution (1979), etc. But the events in North Africa remind us that revolutionary political action is always a possibility, not just a rare political occurrence. Samuel Huntington defines revolution as:

a rapid, fundamental, and violent domestic change in the dominant values and myths of a society, in its political institutions, social structure, leadership, and government activity and policies. Revolutions are thus to be distinguished from insurrections, rebellions, revolts, coups, and wars of independence (Huntington 1968, p. 264).

What is at stake in revolution is also, therefore, the larger question that Max Weber was asking about political action. In a sense, the question of the role of politics in a whole way of life asks how a whole way of life comes into existence in the first place.

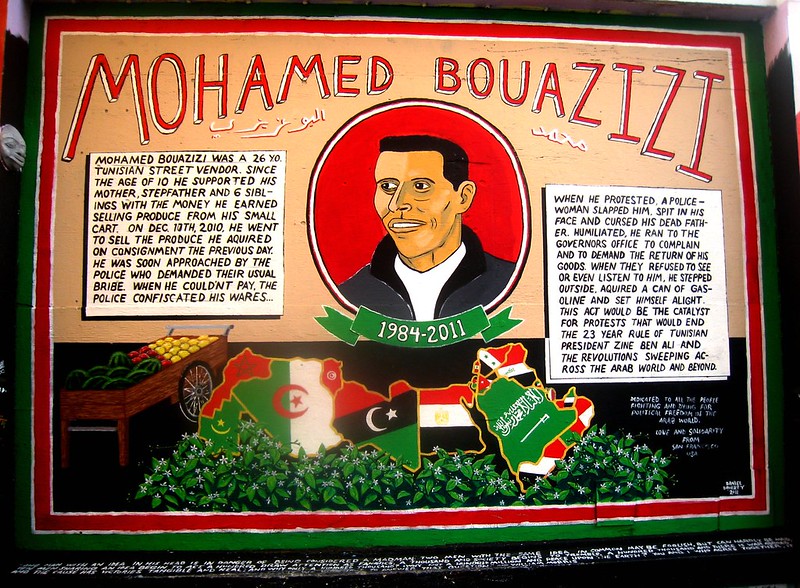

How do revolutions occur? In Tunisia, the street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after his produce cart was confiscated. The injustice of this event provided an emblem for the widespread conditions of poverty, oppression, and humiliation experienced by a majority of the population. In this case, the revolutionary action might be said to have originated in the way that Bouazizi’s act sparked a radicalization in people’s sense of citizenship and power: their internal feelings of individual dignity, rights, and freedom and their capacity to act on them. It was a moment in which, after living through decades of deplorable conditions, people suddenly felt their own power and their own capacity to act. Sociology is interested in studying the conditions of such examples of citizenship and power.

Media Attributions

- Figure 17.1 Mohamed Bouazizi by Niawag, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.