Chapter 19. The Sociology of the Body: Health and Medicine

Learning Objectives

19.1 The Sociology of the Body and Health

- Examine the relationship between the body and society.

- Understand the term biopolitics as a relationship between the body and modern forms of power.

- Understand how medical sociology describes illness and health as social and cultural constructions.

- Define the field of social epidemiology.

- Understand how health issues are affected by the global distribution of wealth.

- Understand how social epidemiology can be applied to the distribution of health outcomes in Canada.

- Explain disparities of health based on gender, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity.

- Give an overview of mental health and disability issues in Canada.

- Explain the terms stigma and medicalization.

19.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Health and Medicine

- Apply functionalist, critical, and symbolic interactionist perspectives to health issues.

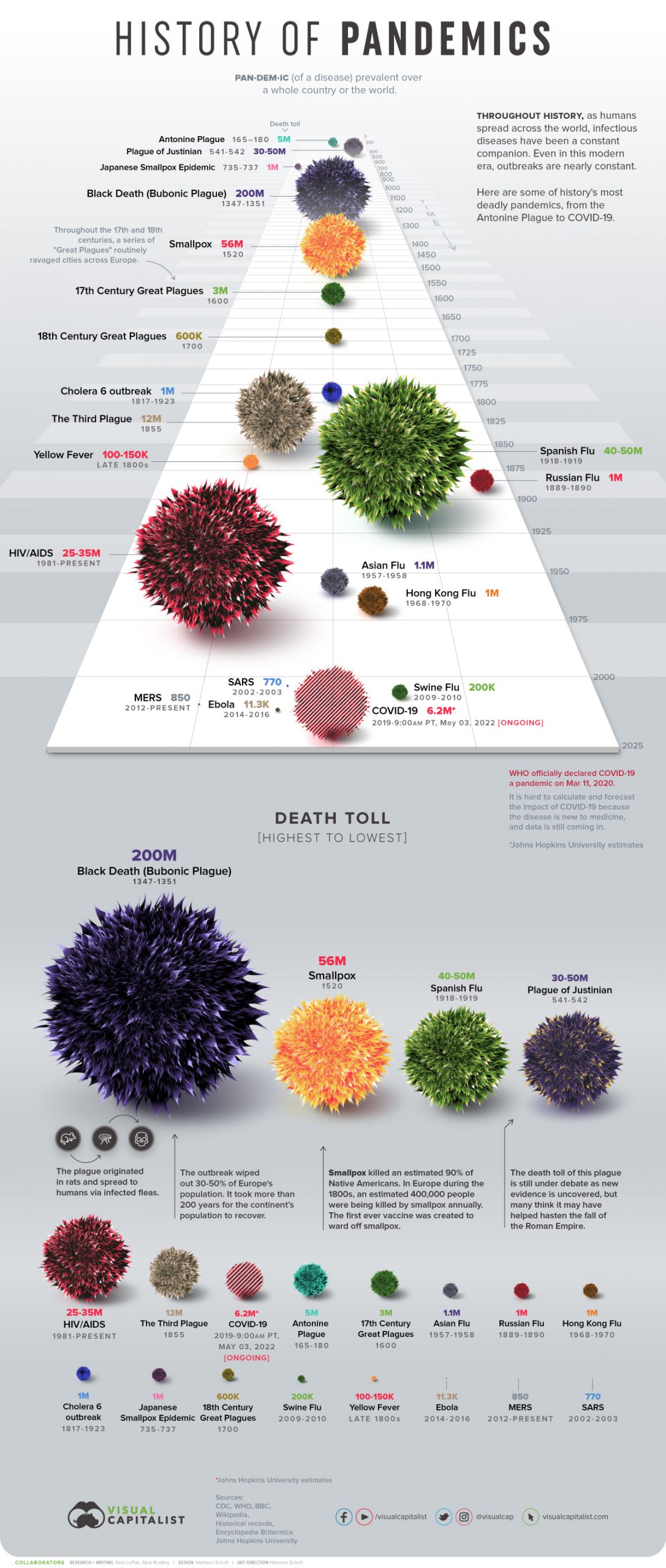

Introduction to Health and Medicine

The COVID-19 virus began to infect humans in 2019 and by March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization had declared it a global pandemic. The virus includes severe acute respiratory syndrome and death among its most serious symptoms. In its first year, the pandemic caused between 1.8 and 3 million deaths worldwide, making it one of the deadliest in history. The common flu generally causes 290 to 650 thousand respiratory deaths each year (WHO, 2022a; WHO, 2022b). In Canada, COVID-19 became the third leading cause of death in 2020, with the loss of 16,151 Canadian lives attributed directly to it (Statistics Canada, 2022).

Like all virus pandemics, the contagion process was social. The virus primarily spreads between people through close social contact. Transmission is via aerosols and respiratory droplets that are exhaled when talking and breathing, as well as those produced from coughs or sneezes (Government of Canada, 2021). Social interaction is the disease vector that carries and transmits the infectious pathogen from person to person.

But this sociological component of the virus was perhaps overshadowed by another social phenomenon: social conflict over the public health measures deployed to combat it. A key part of the COVID-19 pandemic was the rise to prominence of vaccine hesitancy. The World Health Organization defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services” (MacDonald, 2015). Vaccine hesitancy is not a new phenomenon, however.

In 2012, a pertussis (whooping cough) outbreak in B.C., Alberta, Ontario, and New Brunswick sickened 2,000 people and resulted in an infant death in Lethbridge. In the United States, where there were 18,000 cases and nine deaths, it was the worst outbreak in 65 years (Picard, 2012). Researchers, suspecting the primary cause of the outbreak was the waning strength of pertussis vaccines in older children, recommended a booster vaccination for 11–12-year-olds and pregnant women (Zacharyczuk, 2011). Pertussis is most serious for babies — one in five must be hospitalized, and since they are too young for the vaccine themselves, it is crucial that people around them be immunized (Centers for Disease Control 2011). In response to the outbreak, health authorities in various parts of Canada offered free vaccination clinics for parents with infants under one.

Typically Canadian children are vaccinated for whooping cough, diphtheria, and tetanus (a combined vaccine known as DTaP) at ages 2, 4, 6, and 18 months, and then again at ages 4 to 6 years and 14 to 16 years (Picard, 2012). But what of people who do not want their children to have this vaccine, or any other? That question is at the heart of a debate that has been simmering for years. Vaccines are biological preparations that improve immunity against a certain disease. Vaccines have contributed to the eradication and weakening of many infectious diseases in human populations, including smallpox, polio, mumps, chicken pox, and meningitis.

However, many people express concern about potential negative side effects from vaccines. These concerns range from fears about overloading the child’s immune system to contentious reports about devastating side effects of the vaccines. One misapprehension is that the vaccine itself might cause the disease it is supposed to be immunizing. Another commonly circulated concern is that vaccinations, specifically the MMR vaccine (MMR stands for measles, mumps, and rubella), are linked to autism.

The autism connection has been particularly controversial. In 1998, two British physicians, Andrew Wakefield and John Walker-Smith, published a study in Great Britain’s Lancet magazine that linked the MMR vaccine to bowel disease and autism. The report received a lot of media attention, resulting in British immunization rates decreasing from 91% in 1997 to almost 80% by 2003, accompanied by a subsequent rise in measles cases (Devlin, 2008). A prolonged investigation by the British Medical Journal proved the link in the study was nonexistent, and that Dr. Wakefield had falsified data to support his claims (CNN, 2011). Both Dr. Wakefield and Dr. Walker-Smith were discredited and stripped of their licenses, but the doubt still lingers in many parents’ minds. A later ruling in 2012 by the British High Court stated that the British General Medical Council’s charges of misconduct against the two physicians were without basis and that they had never claimed that vaccines caused autism (Aston 2012).

Many parents in Canada still believe in the now-discredited MMR-autism link and refuse to vaccinate their children. Autism is a complex condition of unclear origin, yet the symptoms of its onset occur roughly at the same time as MMR vaccinations. In the absence of clear biomedical explanations for the condition, parents draw their own conclusions or seek alternative explanations. They feel forced to make a risk assessment between the dangers of measles, mumps, and rubella on one side and autism on the other.

Other parents choose not to vaccinate for various reasons like religious or health beliefs. In the United States, a boy whose parents opted not to vaccinate returned home after a trip abroad; no one yet knew he was infected with measles. The boy exposed 839 people to the disease and caused 11 more cases of measles, all in other unvaccinated children, including one infant who had to be hospitalized. According to a study published in Pediatrics, the outbreak cost the public sector $10,376 per diagnosed case. The study further showed that the intentional non-vaccination of those infected occurred in students from private schools, public charter schools, and public schools in upper-socioeconomic areas (Sugerman et al., 2010).

Should parents be forced to immunize their children? What might sociologists make of the fact that most of the families who chose not to vaccinate were of a higher socioeconomic group? How does this story of vaccines in a high-income region compare to that in a low-income region, like sub-Saharan Africa, where populations are often eagerly seeking vaccines rather than refusing them?

Media Attributions

- Figure 19.1 Visualizing the History of Pandemics by Harrison Schell (graphic design), is used by permission of Visual Capitalist.