Chapter 4. Society and Modern Life

Learning Objectives

- Compare ways of understanding the evolution of human societies.

- Describe the difference between preindustrial, industrial, postindustrial and postnatural societies.

- Understand how a society’s relationship to the environment impacts societal development.

4.2. Theoretical Perspectives on the Formation of Modern Society

- Compare Durkheim’s functionalist view of modern society with Marx’s critical view and Weber’s interpretive view.

- Explain the difference between Durkheim’s concept of anomie, Marx’s concept of alienation and Weber’s concept of rationalization.

- Conrast androcentric perspectives with how feminists analyze the development of society.

4.3. Living in Contemporary Society

- Describe how Durkheim’s, Marx’s and Weber’s analyses can be updated and applied to social life in the 21st century.

Introduction to Society

In 1900, a young anthropologist, John Swanton, transcribed a series of myths and tales — known as qqaygaang in the Haida language — told by the master Haida storyteller Ghandl. The tales tell stories of animal and human transformations, of heroes who marry birds, of birds who take off their skins and become women, of mussels who manifest the spirit form of whales, and of people who climb poles to the sky.

After she’d offered him something to eat, Mouse Woman said to him, “When I was bringing a bit of cranberry back from my berry patch, you helped me. I intend to lend you something I wore for stalking prey when I was younger.”

She brought out a box. She pulled out four more boxes within boxes. In the innermost box was the skin of a mouse with small bent claws. She said to him, “Put this on.”

Small though it was, he got into it. It was easy. He went up the wall and onto the roof of the house. And Mouse Woman said to him, “You know what to do when you wear it. Be on your way” (Ghandl, quoted in Bringhurst, 2011).

To the ear of contemporary Canadians, these types of tales often seem confusing. They lack the familiar inner psychological characterization of protagonists and antagonists, the “realism” of natural settings and chronological time sequences, or the standard plot devices of man against man, man against himself, and man against nature. However, as Robert Bringhurst (2011) argues, this is not because the tales are not great literature or have not completely “evolved.” In his estimation, Ghandl should be recognized as one of the most brilliant storytellers who has ever lived in Canada. Rather, it is because the stories speak to, and from, a fundamentally different experience of the world: the experience of nomadic hunting and gathering people as compared to the sedentary people of modern capitalist societies. How does the way we tell stories reflect the organization and social structures of the societies we live in?

Ghandl’s tales are told within an oral tradition rather than a written or literary tradition. They are meant to be listened to, not read, and as such the storytelling skill involves weaving in subtle repetitions and numerical patterns, and plays on Haida words and well-known mythological images rather than creating page-turning dramas of psychological or conflictual suspense. Bringhurst suggests that even compared to the Indo-European oral tradition going back to Homer or the Vedas, the Haida tales do not rely on the auditory conventions of verse. Whereas verse relies on acoustic devices like alliteration and rhyming, Haida mythic storytelling was a form of noetic prosody, relying on patterns of ideas and images. The Haida, as a non-agricultural people, did not see a reason to add overt musical qualities to their use of language. “[V]erse in the strictly acoustic sense of the word does not play the same role in preagricultural societies. Humans, as a rule, do not begin to farm their language until they have begun to till the earth and to manipulate the growth of plants and animals.” As Bringhurst puts it, “myth is that form of language in which poetry and music have not as yet diverged“(Bringhurst, 2011, italics in original).

Perhaps more significantly for sociologists, the hunting and gathering lifestyle of the Haida also produces a very different relationship to the natural world and to the non-human creatures and plants with which they coexisted. This is manifest in the tales of animal-human-spirit transformations and in their moral lessons, which caution against treating the world with disrespect. With regard to understanding Haida storytelling, Bringhurst argues:

following the poetry they [hunting gathering peoples] make is more like moving through a forest or a canyon, or waiting in a blind, than moving through an orchard or field. The language is often highly ordered, rich, compact — but it is not arranged in neat, symmetrical rows (2011).

In other words, for the hunter who follows animal traces through the woods, or waits patiently for hours in a hunting blind or fishing spot for wild prey to appear, the relationship to the prey is much more akin to “putting on their skins” or spiritually “becoming-animal” than to be a shepherd raising and caring for livestock. A successful hunting and gathering people would be inclined to study how animals think from the inside, rather than controlling or manipulating them from the outside. For the Haida, tales of animal transformations would not seem so fantastic or incomprehensible as they do to modern people who spend most of their life indoors. They would be part of their “acutely personal relations with the wild” (Bringhurst, 2011).

Similarly, the Haida ethics, embodied in their tales and myths, acknowledge a complex web of unwritten contracts between humans, animal species, and spirit-beings.

The culture as Ghandl describes it depends — like every hunting culture — not on control of the land as such but on control of the human demands that are placed upon it (Bringhurst, 2011).

In the Haida tales, humans continually confront a world of living beings and forces that are much more powerful and intelligent than they are, and who are quick to take offense at human stupidity and hubris.

What sociologists learn from the detailed studies of the Haida and their literature is how a fundamentally different social relationship to the environment affects the way people think and how they see their place in the world. Nevertheless, although the traditional Haida society of Haida Gwaii in the Pacific Northwest is very different from contemporary post-industrial Canada, both can be seen as different ways of expressing the human need to cooperate and live together to survive. For the sociologist, this is a lesson in how the type of society one lives in — its scale and social structure — impacts one’s experience of the world at a fundamental, even perceptual level.

Media Attributions

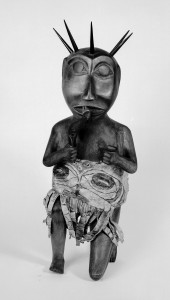

- Figure 4.1 Effigy of a Shaman from Haida Tribe, late 19th century from Wellcome Library, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

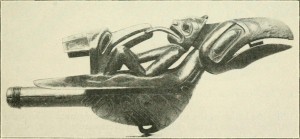

- Figure 4.2 Ceremonial rattle in the form of the mythical thunder-bird from page 313 of the British Museum Handbook to the Ethnographical Collections (1910) by Internet Archive Book Images, via Flickr, is in the public domain.