Chapter 1 Introduction to Geology

1.5 Fundamentals of Plate Tectonics

Plate tectonics is the model or theory that has been used for the past 60 years to understand and explain how the Earth works—more specifically the origins of continents and oceans, of folded rocks and mountain ranges, of earthquakes and volcanoes, and of continental drift. Plate tectonics is explained in some detail in Chapter 10, but is introduced here because it includes concepts that are important to many of the topics covered in the next few chapters.

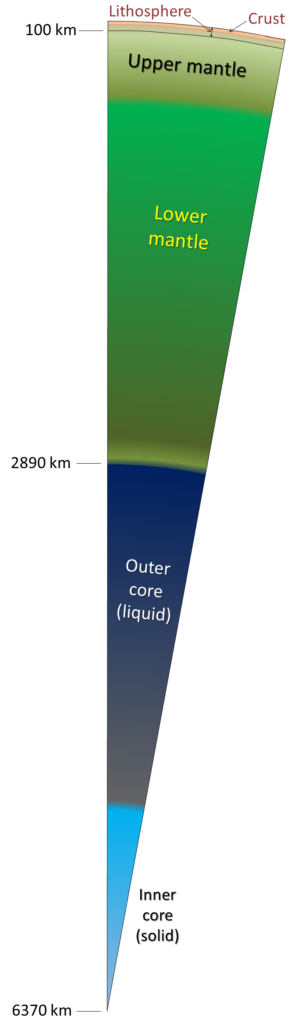

Key to understanding plate tectonics is an understanding of Earth’s internal structure, which is illustrated in Figure 1.5.1. Earth’s core consists mostly of iron. The outer core is hot enough for the iron to be liquid. The inner core—although even hotter—is under so much pressure that it is solid. The mantle is made up of iron and magnesium silicate minerals. The bulk of the mantle surrounding the outer core is solid rock, but is plastic enough to be able to flow slowly. The outermost part of the mantle is rigid. The crust—composed mostly of granite on the continents and mostly of basalt beneath the oceans—is also rigid. The crust and outermost rigid mantle together make up the lithosphere. The lithosphere is divided into about 20 tectonic plates that move in different directions on Earth’s surface.

An important property of Earth (and other planets) is that the temperature increases with depth, from close to 0°C at the surface to about 7000°C at the centre of the core. In the crust, the rate of temperature increase is about 30°C every kilometre. This is known as the geothermal gradient.

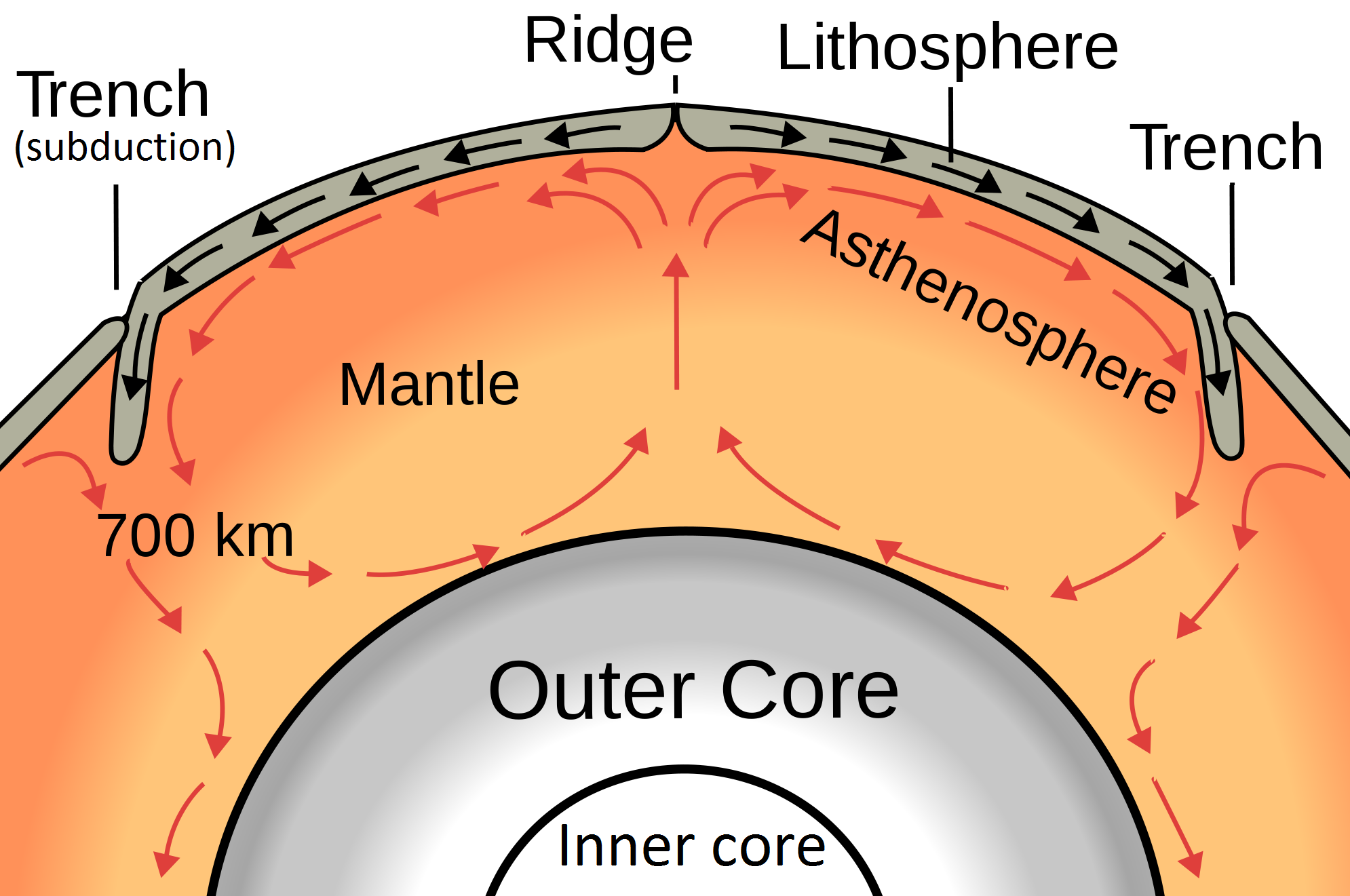

Heat is continuously flowing outward from Earth’s interior, and the transfer of heat from the core to the mantle causes convection in the mantle (Figure 1.5.2). This convection is the primary driving force for the movement of tectonic plates. At places where convection currents in the mantle are moving upward, new lithosphere forms (at ocean ridges), and the plates move apart (diverge). Where two plates are converging (and the convective flow is downward), one plate will be subducted (pushed down) into the mantle beneath the other. Many of Earth’s major earthquakes and volcanoes are associated with convergent boundaries.

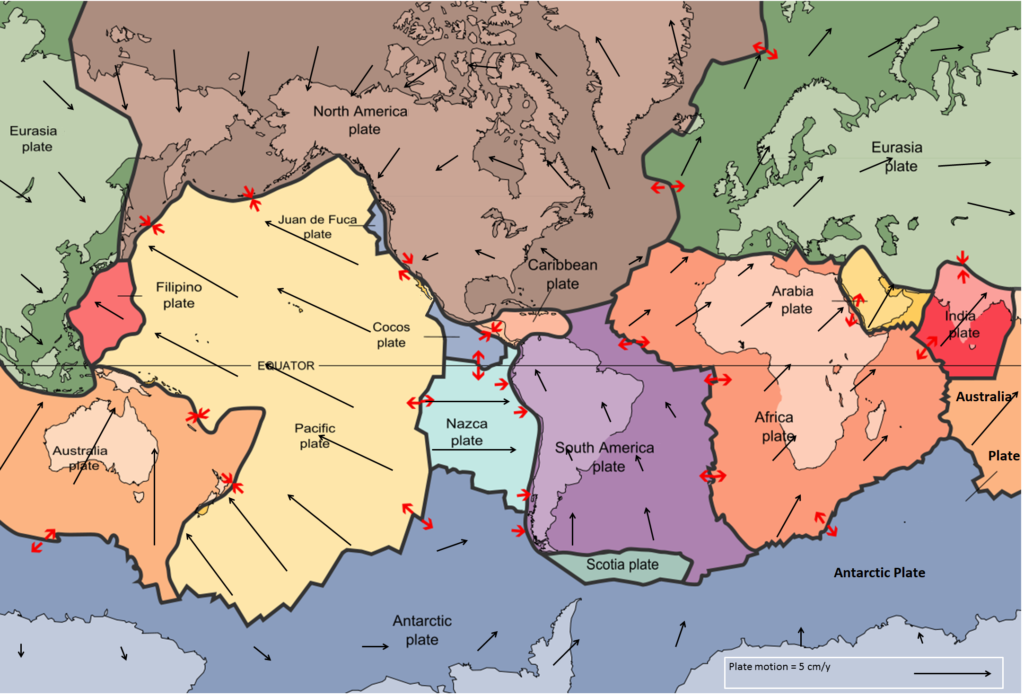

Earth’s major tectonic plates and the directions and rates at which they are diverging at sea-floor ridges, are shown in Figure 1.5.3.

Exercise 1.2 Plate

Using either a map of the tectonic plates from the Internet or Figure 1.5.3 determine which tectonic plate you are on right now, approximately how fast it is moving, and in what direction. How far has that plate moved relative to Earth’s core since you were born?

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 1.2 answers.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.5.1: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 1.5.2: Oceanic Spreading by Surachit. Public domain.

- Figure 1.5.3: Tectonic Plates by USGS. Public domain. Adapted by Steven Earle.

The concept that the Earth’s crust and upper mantle (lithosphere) is divided into a number of plates that move independently on the surface and interact with each other at their boundaries.

The metallic interior part of the Earth, extending from a depth of 2900 kilometres to the centre.

The middle layer of the Earth, dominated by iron and magnesium rich silicate minerals and extending for about 2900 kilometres from the base of the crust to the top of the core.

A mineral that includes silica tetrahedra.

The uppermost layer of the Earth, ranging in thickness from about 5 kilometres (in the oceans) to over 50 kilometres (on the continents).

The rigid outer part of the Earth, including the crust and the mantle down to a depth of about 100 kilometres.

A region of the lithosphere that is considered to be moving across the surface of the Earth as a single unit.

The rate of increase of temperature with depth in the Earth (typically around 30˚ C/km within the crust).

When part of a plate is forced beneath another plate along a subduction zone.