1. Operations with Real Numbers

1.6 Roots and Radicals

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section it is expected that you will be able to:

- Simplify expressions with roots

- Estimate and approximate roots

- Use radicals in applications

Simplify Expressions with Square Roots

Remember that when a number n is multiplied by itself, we write ![]() and read it “n squared.” The result is called the square of n. For example,

and read it “n squared.” The result is called the square of n. For example,

Similarly, 121 is the square of 11, because ![]() is 121.

is 121.

Square of a Number

If ![]() then m is the square of n.

then m is the square of n.

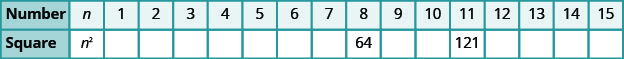

Complete the following table to show the squares of the counting numbers 1 through 15.

The numbers in the second row are called perfect square numbers. It will be helpful to learn to recognize the perfect square numbers.

The squares of the counting numbers are positive numbers. What about the squares of negative numbers? We know that when the signs of two numbers are the same, their product is positive. So the square of any negative number is also positive.

Did you notice that these squares are the same as the squares of the positive numbers?

Sometimes we will need to look at the relationship between numbers and their squares in reverse. Because ![]() we say 100 is the square of 10. We also say that 10 is a square root of 100. A number whose square is

we say 100 is the square of 10. We also say that 10 is a square root of 100. A number whose square is ![]() is called a square root of m.

is called a square root of m.

Square Root of a Number

If ![]() then n is a square root of m.

then n is a square root of m.

Notice ![]() also, so

also, so ![]() is also a square root of 100. Therefore, both 10 and

is also a square root of 100. Therefore, both 10 and ![]() are square roots of 100.

are square roots of 100.

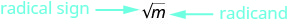

So, every positive number has two square roots—one positive and one negative. What if we only wanted the positive square root of a positive number? The radical sign, ![]() denotes the positive square root. The positive square root is called the principal square root. When we use the radical sign that always means we want the principal square root.

denotes the positive square root. The positive square root is called the principal square root. When we use the radical sign that always means we want the principal square root.

We also use the radical sign for the square root of zero. Because ![]()

![]() Notice that zero has only one square root.

Notice that zero has only one square root.

Square Root Notation

![]() is read “the square root of m”

is read “the square root of m”

If ![]() then

then ![]() for

for ![]()

The square root of m, ![]() is the positive number whose square is m.

is the positive number whose square is m.

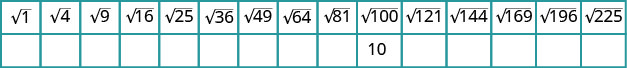

Since 10 is the principal square root of 100, we write ![]() You may want to complete the following table to help you recognize square roots.

You may want to complete the following table to help you recognize square roots.

EXAMPLE 1

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

| a) Since |

|

| b) Since |

TRY IT 1

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Show answer

a) 6 b) 13

We know that every positive number has two square roots and the radical sign indicates the positive one. We write ![]() If we want to find the negative square root of a number, we place a negative in front of the radical sign. For example,

If we want to find the negative square root of a number, we place a negative in front of the radical sign. For example, ![]() We read

We read ![]() as “the opposite of the square root of 100.”

as “the opposite of the square root of 100.”

EXAMPLE 2

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

| a) The negative is in front of the radical sign. |

|

| b) The negative is in front of the radical sign. |

TRY IT 2

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Show answer

a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Can we simplify ![]() Is there a number whose square is

Is there a number whose square is ![]()

Any positive number squared is positive. Any negative number squared is positive. There is no real number equal to ![]() The square root of a negative number is not a real number.

The square root of a negative number is not a real number.

EXAMPLE 3

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Solution

a)

| There is no real number whose square is |

b)

| The negative is in front of the radical. |

TRY IT 3

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Show answer

a) not a real number b) ![]()

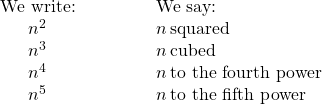

So far we have only talked about squares and square roots. Let’s now extend our work to include higher powers and higher roots.

Let’s review some vocabulary first.

The terms ‘squared’ and ‘cubed’ come from the formulas for area of a square and volume of a cube.

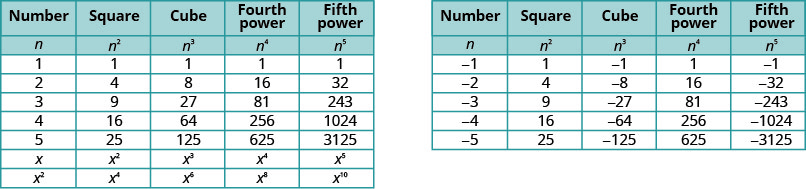

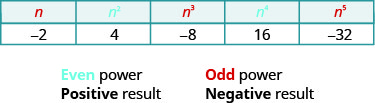

It will be helpful to have a table of the powers of the integers from −5 to 5. See (Table 1).

Notice the signs in the table. All powers of positive numbers are positive, of course. But when we have a negative number, the even powers are positive and the odd powers are negative. We’ll copy the row with the powers of −2 to help you see this.

We will now extend the square root definition to higher roots.

nth Root of a Number

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{}\\ \\ \hfill \text{If}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{b}^{n}=a,\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{then}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}b\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{is an}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{n}^{th}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{root of}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}a.\hfill \\ \hfill \text{The principal}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{n}^{th}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{root of}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}a\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{is written}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\sqrt[n]{a}.\hfill \\ \hfill n\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{is called the}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\mathbf{\text{index}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{of the radical.}\hfill \end{array}](https://opentextbc.ca/businesstechnicalmath/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bce73c1457e00d949ea81a709b17a46c_l3.png)

Just like we use the word ‘cubed’ for b3, we use the term ‘cube root’ for ![]()

We can refer to (Table 1) to help find higher roots.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{array}{ccc}\hfill {4}^{3}& =\hfill & 64\hfill \\ \hfill {3}^{4}& =\hfill & 81\hfill \\ \hfill {\left(-2\right)}^{5}& =\hfill & -32\hfill \end{array}\phantom{\rule{6em}{0ex}}\begin{array}{ccc}\hfill \sqrt[3]{64}& =\hfill & 4\hfill \\ \hfill \sqrt[4]{81}& =\hfill & 3\hfill \\ \hfill \sqrt[5]{-32}& =\hfill & -2\hfill \end{array}](https://opentextbc.ca/businesstechnicalmath/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ae49f158b7d5f39bdd200b083c538371_l3.png)

Could we have an even root of a negative number? We know that the square root of a negative number is not a real number. The same is true for any even root. Even roots of negative numbers are not real numbers. Odd roots of negative numbers are real numbers.

Properties of ![]()

When n is an even number and

then

then ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \sqrt[n]{a}](https://opentextbc.ca/businesstechnicalmath/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1c6b7326bec5fc086e8335bb7e382f30_l3.png) is a real number.

is a real number. then

then ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \sqrt[n]{a}](https://opentextbc.ca/businesstechnicalmath/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1c6b7326bec5fc086e8335bb7e382f30_l3.png) is not a real number.

is not a real number.

When n is an odd number, ![]() is a real number for all values of a.

is a real number for all values of a.

We will apply these properties in the next two examples.

EXAMPLE 4

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]() c)

c) ![]()

Solution

a)

| Since |

4 |

b)

| Since |

3 |

c)

| Since |

2 |

TRY IT 4

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]() c)

c) ![]()

Show answer

a) 3 b) 4 c) 3

In this example be alert for the negative signs as well as even and odd powers.

EXAMPLE 5

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]() c)

c) ![]()

Solution

a)

| Since |

|

b)

| Think, |

Not a real number. |

c)

| Since |

TRY IT 5

Simplify: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]() c)

c) ![]()

Show answer

a) ![]() b) not real c)

b) not real c) ![]()

Estimate and Approximate Roots

When we see a number with a radical sign, we often don’t think about its numerical value. While we probably know that the ![]() what is the value of

what is the value of ![]() or

or ![]() In some situations a quick estimate is meaningful and in others it is convenient to have a decimal approximation.

In some situations a quick estimate is meaningful and in others it is convenient to have a decimal approximation.

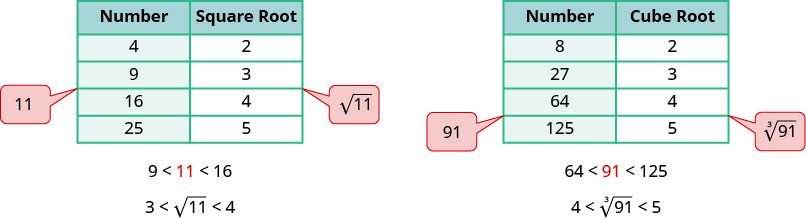

To get a numerical estimate of a square root, we look for perfect square numbers closest to the radicand. To find an estimate of ![]() we see 11 is between perfect square numbers 9 and 16, closer to 9. Its square root then will be between 3 and 4, but closer to 3.

we see 11 is between perfect square numbers 9 and 16, closer to 9. Its square root then will be between 3 and 4, but closer to 3.

Similarly, to estimate ![]() we see 91 is between perfect cube numbers 64 and 125. The cube root then will be between 4 and 5.

we see 91 is between perfect cube numbers 64 and 125. The cube root then will be between 4 and 5.

EXAMPLE 6

Estimate each root between two consecutive whole numbers: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Solution

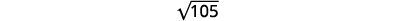

a) Think of the perfect square numbers closest to 105. Make a small table of these perfect squares and their squares roots.

|

|

|

|

| Locate 105 between two consecutive perfect squares. |  |

|

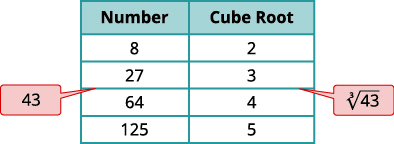

b) Similarly we locate 43 between two perfect cube numbers.

|

|

|

|

| Locate 43 between two consecutive perfect cubes. |  |

|

TRY IT 6

Estimate each root between two consecutive whole numbers:

a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

Show answer

a) ![]()

b) ![]()

![]() There are mathematical methods to approximate square roots, but nowadays most people use a calculator to find square roots. To find a square root you will use the

There are mathematical methods to approximate square roots, but nowadays most people use a calculator to find square roots. To find a square root you will use the ![]() key on your calculator. To find a cube root, or any root with higher index, you will use the

key on your calculator. To find a cube root, or any root with higher index, you will use the ![]() key.

key.

When you use these keys, you get an approximate value. It is an approximation, accurate to the number of digits shown on your calculator’s display. The symbol for an approximation is ![]() and it is read ‘approximately’.

and it is read ‘approximately’.

Suppose your calculator has a 10 digit display. You would see that

How do we know these values are approximations and not the exact values? Look at what happens when we square them:

Their squares are close to 5, but are not exactly equal to 5. The fourth powers are close to 93, but not equal to 93.

EXAMPLE 7

Round to two decimal places: a) ![]() b)

b) ![]() c)

c) ![]()

Solution

a)

| Use the calculator square root key. | |

| Round to two decimal places. | |

b)

| Use the calculator |

|

| Round to two decimal places. | |

| |

c)

| Use the calculator |

|

| Round to two decimal places. | |

TRY IT 7

Round to two decimal places:

a) ![]() b)

b) ![]() c)

c) ![]()

Show answer

a) ![]() b)

b) ![]()

c) ![]()

Use Radicals in Applications

As you progress through your college or university courses, you’ll encounter formulas that include radicals in many disciplines. We will modify our Problem Solving Strategy for Geometry Applications slightly to give us a plan for solving applications with formulas from any discipline.

Use a problem solving strategy for applications with formulas.

- Read the problem and make sure all the words and ideas are understood. When appropriate, draw a figure and label it with the given information.

- Identify what we are looking for.

- Name what we are looking for by choosing a variable to represent it.

- Translate into an equation by writing the appropriate formula or model for the situation. Substitute in the given information.

- Solve the equation using good algebra techniques.

- Check the answer in the problem and make sure it makes sense.

- Answer the question with a complete sentence.

One application of radicals has to do with the effect of gravity on falling objects. The formula allows us to determine how long it will take a fallen object to hit the gound.

Falling Objects

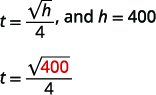

On Earth, if an object is dropped from a height of h feet, the time in seconds it will take to reach the ground is found by using the formula

For example, if an object is dropped from a height of 64 feet, we can find the time it takes to reach the ground by substituting ![]() into the formula.

into the formula.

|

|

|

|

| Take the square root of 64. |  |

| Simplify the fraction. |  |

It would take 2 seconds for an object dropped from a height of 64 feet to reach the ground.

EXAMPLE 8

Marissa dropped her sunglasses from a bridge 400 feet above a river. Use the formula ![]() to find how many seconds it took for the sunglasses to reach the river.

to find how many seconds it took for the sunglasses to reach the river.

Solution

| Step 1. Read the problem. | |

| Step 2. Identify what we are looking for. | the time it takes for the

sunglasses to reach the river |

| Step 3. Name what we are looking. | Let |

| Step 4. Translate into an equation by writing the

appropriate formula. Substitute in the given information. |

|

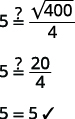

| Step 5. Solve the equation. |  |

|

|

| Step 6. Check the answer in the problem and make

sure it makes sense. |

|

| Does 5 seconds seem like a reasonable length of

time? |

Yes. |

| Step 7. Answer the question. | It will take 5 seconds for the

sunglasses to reach the river. |

TRY IT 8

A helicopter dropped a rescue package from a height of 1,296 feet. Use the formula ![]() to find how many seconds it took for the package to reach the ground.

to find how many seconds it took for the package to reach the ground.

Show answer

9 seconds

Police officers investigating car accidents measure the length of the skid marks on the pavement. Then they use square roots to determine the speed, in miles per hour, a car was going before applying the brakes.

Skid Marks and Speed of a Car

If the length of the skid marks is d feet, then the speed, s, of the car before the brakes were applied can be found by using the formula

EXAMPLE 9

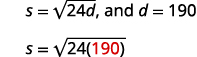

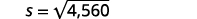

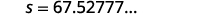

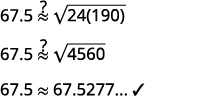

After a car accident, the skid marks for one car measured 190 feet. Use the formula ![]() to find the speed of the car before the brakes were applied. Round your answer to the nearest tenth.

to find the speed of the car before the brakes were applied. Round your answer to the nearest tenth.

Solution

| Step 1. Read the problem | |

| Step 2. Identify what we are looking for. | the speed of a car |

| Step 3. Name what we are looking for, | Let |

| Step 4. Translate into an equation by writing

the appropriate formula. Substitute in the given information. |

|

| Step 5. Solve the equation. |  |

|

|

| Round to 1 decimal place. |  |

|

|

| The speed of the car before the brakes were applied

was 67.5 miles per hour. |

TRY IT 9

An accident investigator measured the skid marks of the car. The length of the skid marks was 76 feet. Use the formula ![]() to find the speed of the car before the brakes were applied. Round your answer to the nearest tenth.

to find the speed of the car before the brakes were applied. Round your answer to the nearest tenth.

Show answer

![]() feet

feet

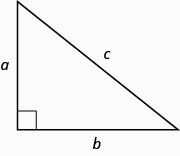

The Pythagorean Theorem tells how the lengths of the three sides of a right triangle relate to each other. It states that in any right triangle, the sum of the squares of the two legs equals the square of the hypotenuse.

The Pythagorean Theorem

In any right triangle ![]() ,

,

where ![]() is the length of the hypotenuse

is the length of the hypotenuse ![]() and

and ![]() are the lengths of the legs.

are the lengths of the legs.

We will use this definition of square roots to solve for the length of a side in a right triangle.

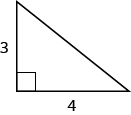

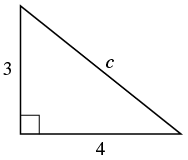

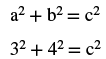

EXAMPLE 10

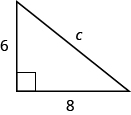

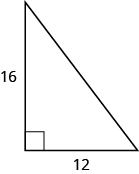

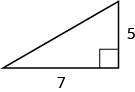

Use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the hypotenuse.

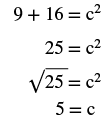

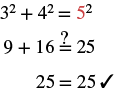

Solution

| Step 1. Read the problem. | |

| Step 2. Identify what you are looking for. | the length of the hypotenuse of the triangle |

| Step 3. Name. Choose a variable to represent it. | Let  |

| Step 4. Translate. Write the appropriate formula. Substitute. |

|

| Step 5. Solve the equation. |  |

Step 6. Check: |

|

| Step 7. Answer the question. | The length of the hypotenuse is 5. |

TRY IT 10

Use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the hypotenuse.

Show answer

10

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with solving radical equations.

Glossary

square root notation

is read ‘the square root of m’

is read ‘the square root of m’- If n2 = m, then

for

for

- The square root of m,

is a positive number whose square is m.

is a positive number whose square is m.

nth root of a number

- If

then b is an nth root of a.

then b is an nth root of a. - The principal nth root of a is written

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \sqrt[n]{a}.](https://opentextbc.ca/businesstechnicalmath/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8926ea991916fb34abf938092c039c24_l3.png)

- n is called the index of the radical.

1.6 Exercise Set

In the following exercises, simplify.

In the following exercises, estimate each root between two consecutive whole numbers.

In the following exercises, approximate each root and round to two decimal places.

In the following exercises, solve. Round approximations to one decimal place.

- Landscaping. Reed wants to have a square garden plot in his backyard. He has enough compost to cover an area of 75 square feet. Use the formula

to find the length of each side of his garden. Round your answer to the nearest tenth of a foot.

to find the length of each side of his garden. Round your answer to the nearest tenth of a foot. - Gravity. A hang glider dropped his cell phone from a height of 350 feet. Use the formula

to find how many seconds it took for the cell phone to reach the ground.

to find how many seconds it took for the cell phone to reach the ground. - Accident investigation The skid marks for a car involved in an accident measured 216 feet. Use the formula

to find the speed of the car before the brakes were applied. Round your answer to the nearest tenth.

to find the speed of the car before the brakes were applied. Round your answer to the nearest tenth.

-

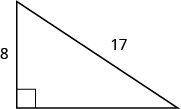

In the following exercises, use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the hypotenuse.

17.

18.

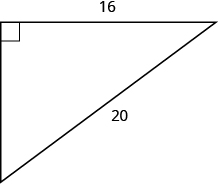

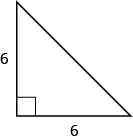

In the following exercises, use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the missing side. Round to the nearest tenth, if necessary.

19.

20.

21 .

22.

Answers:

-

- 8

-

-

- 14

-

-

- not real number

-

- not real number

-

- 6

- 4

-

- 8

- 3

- 1

-

-

-

-

-

-

feet

feet seconds

seconds- 72 feet

- 20

- 13

- 15

- 12

- 8.5

- 8.6

Attributions ( imported from my Introductory Algebra)

-

This chapter has been adapted from “The Real Numbers” in Elementary Algebra (OpenStax) by Lynn Marecek and MaryAnne Anthony-Smith, which is under a CC BY 4.0 Licence. Adapted by Izabela Mazur. See the Copyright page for more information.