Chapter 8. Intravenous Therapy

8.2 Intravenous Fluid Therapy

Intravenous therapy is treatment that infuses intravenous solutions, medications, blood, or blood products directly into a vein (Perry, Potter, & Ostendorf, 2014). Intravenous therapy is an effective and fast-acting way to administer fluid or medication treatment in an emergency situation, and for patients who are unable to take medications orally. Approximately 80% of all patients in the hospital setting will receive intravenous therapy.

The most common reasons for IV therapy (Waitt, Waitt, & Pirmohamed, 2004) include:

- To replace fluids and electrolytes and maintain fluid and electrolyte balance: The body’s fluid balance is regulated through hormones and is affected by fluid volumes, distribution of fluids in the body, and the concentration of solutes in the fluid. If a patient is ill and has fluid loss related to decreased intake, surgery, vomiting, diarrhea, or diaphoresis, the patient may require IV therapy.

- To administer medications, including chemotherapy, anesthetics, and diagnostic reagants: About 40% of all antibiotics are given intravenously.

- To administer blood or blood products: The donated blood from another individual can be used in surgery, to treat medical conditions such as shock or trauma, or to treat a failure in the production of red blood cells. The infusion restores circulating volumes, improving the ability to carry oxygen and replace blood components that are deficient in the body.

- To deliver nutrients and nutritional supplements: IV therapy can deliver some or all of the nutritional requirements for patients unable to obtain adequate amounts orally or by other routes.

Guidelines Related to Intravenous Therapy

The following are general guidelines for peripheral IV therapy:

- IV fluid therapy is ordered by a physician or nurse practitioner. The order must include the type of solution or medication, rate of infusion, duration, date, and time. IV therapy may be for short or long duration, depending on the needs of the patient (Perry et al, 2014).

- IV therapy is an invasive procedure, and therefore significant complications can occur if the wrong amount of IV fluids or the incorrect medication is given.

- Aseptic technique must be maintained throughout all IV therapy procedures, including initiation of IV therapy, preparing and maintaining equipment, and discontinuing an IV system. Always perform hand hygiene before handling all IV equipment. If an administration set or solution becomes contaminated with a non-sterile surface, it should be replaced with a new one to prevent introducing bacteria or other contaminants into the system (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2011).

- Understand the indications and duration for IV therapy for each patient. Practice guidelines recommend that patients receiving IV therapy for more than six days should be assessed for an intermediate or long-term device (CDC, 2011).

- If a patient has an order to keep a vein open, or “TKVO,” the usual rate of infusion is 20 to 50 ml per hour (Fraser Health Authority, 2014).

- Complications may occur with IV therapy, including but not limited to localized infection, catheter-related bloodstream infection (CR-BSI), fluid overload, and complications related to the type and amount of solution or medication given (Perry et al., 2014).

- For an infusing peripheral IV, the site must be assessed every 2 hours and p.r.n.

- A saline lock site must be assessed every 12 hours and p.r.n.

Types of Venous Access

Safe and reliable venous access for infusions is a critical component of patient care in the acute and community health setting. There are a variety of options available, and a venous access device must be selected based on the duration of IV therapy, type of medication or solution to be infused, and the needs of the patient. In practice, it is important to understand the options of appropriate devices available. This section will describe two types of venous access: peripheral IV access and central venous catheters.

Peripheral IV

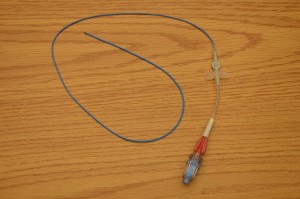

A peripheral IV is a common, preferred method for short-term IV therapy in the hospital setting. A peripheral IV (PIV) (see Figure 8.1) is a short intravenous catheter inserted by percutaneous venipuncture into a peripheral vein, held in place with a sterile transparent dressing to keep the site sterile and prevent accidental dislodgement (CDC, 2011). Upper extremities (hands and arms) are the preferred sites for insertion by a specially trained health care provider. If a lower extremity is used, remove the peripheral IV and re-site in the upper extremities as soon as possible (CDC, 2011; McCallum & Higgins, 2012). The hub of a short intravenous catheter is usually attached to IV extension tubing with a positive pressure cap (Fraser Health Authority, 2014).

PIVs are used for infusions under six days and for solutions that are iso-osmotic or near iso-osmotic (CDC, 2011). They are easy to monitor and can be inserted at the bedside. CDC (2011) recommends that PIVs be replaced every 72 to 96 hours to prevent infection and phlebitis in adults. Most agencies require training to initiate IV therapy, but the care and preparation of equipment, and the maintenance of an IV system can be completed each shift by the trained health care provider. For more information on how to initiate IV therapy, see the resources at the end of the chapter.

PIVs are prone to phlebitis and infection, and should be removed (CDC, 2011) as follows:

- Every 72 to 96 hours and p.r.n.

- As soon as the patient is stable and no longer requires IV fluid therapy

- As soon as the patient is stable following insertion of a cannula in an area of flexion

- Immediately if tenderness, swelling, redness, or purulent drainage occurs at the insertion site

- When the administration set is changed (IV tubing)

Several potential complications may arise from peripheral intravenous therapy. It is the responsibility of the health care provider to monitor for signs and symptoms of complications and intervene appropriately. Complications can be categorized as local or systemic. Most complications are avoidable if simple hand hygiene and safe principles are adhered to for each patient at every point of contact (Fraser Health Authority, 2014; McCallum & Higgins, 2012). Table 8.1 lists the potential local and complications and treatment.

|

Complication |

Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment |

||

| Phlebitis | Phlebitis is the inflammation of the vein’s inner lining, the tunica intima. Clinical indications are localized redness, pain, heat, and swelling, which can track up the vein leading to a palpable venous cord.

Mechanical causes: Inflammation of the vein’s inner lining can be caused by the cannula rubbing and irritating the vein. It is recommended to use the smallest gauge possible to deliver the medication or required fluids. Chemical causes: Inflammation of the vein’s inner lining can be caused by medications with a high alkaline, acidic, or hypertonic solutions. To avoid chemical phlebitis, follow the Parenteral Drug Therapy Manual (PDTM) guidelines for administering IV medications for the appropriate amount of solution and rate of infusion. Treatment: Immediately remove cannula. May elevate arm or apply a warm compress. Document findings in chart. Initiate a new peripheral IV if necessary. |

||

| Infiltration | Infiltration occurs when a non-vesicant solution (IV solution) is inadvertently administered into surrounding tissue. Signs and symptoms include pain, swelling, redness, skin surrounding insertion site is cool to touch, change in quality or flow of IV, tight skin around IV site, IV fluid leaking from IV site, and frequent alarms on the IV pump.

Treatment: Stop infusion and remove cannula. Follow agency policy related to infiltration. Always secure peripheral catheter with tape or IV stabilization device to avoid accidental dislodgement. Avoid areas of flexion and always assess IV site prior to giving IV fluids or IV medications. |

||

| Extravasation | Extravasation occurs when vesicant solution (medication) is administered and inadvertently leaks into surrounding tissue, causing damage to surrounding tissue. Characterized by the same signs and symptoms as infiltration but also includes burning, stinging, redness, blistering, or necrosis of the tissue.

Treatment: Stop infusion and remove cannula. Follow agency policy for extravasation for specific medications. For example, toxic medications have a specific treatment plan. |

||

| Hemorrhage | Hemorrhage is defined as bleeding from the puncture site.

Treatment: Apply gauze to the site until the bleeding stops, then apply a sterile transparent dressing. |

||

| Local infection at IV site | Local infection is indicated by purulent drainage from site, usually two to three days after an IV site is started.

Treatment: Remove cannula and clean site using sterile technique. Monitor for signs and symptoms of systemic infection. |

||

| Data source: Fraser Health Authority, 2014; McCallum & Higgins, 2012 | |||

Systemic complications can occur apart from chemical or mechanical complications. To review the systemic complications of IV therapy, see Table 8.2.

Safety considerations:

|

|||

|

Complication |

Signs, Symptoms and Treatment |

||

| Pulmonary edema | Pulmonary edema, also known as fluid overload or circulatory overload, is a condition caused by excess fluid accumulation in the lungs, due to excessive fluid in the circulatory system. It is characterized by decreased oxygen saturation, increased respiratory rate, fine or coarse crackles at lung bases, restlessness, breathlessness, dyspnea, and coughing up pinky frothy sputum. Pulmonary edema requires prompt medical attention and treatment. If pulmonary edema is suspected, raise the head of the bed, apply oxygen, take vital signs, complete a cardiovascular assessment, and notify the physician. | ||

| Air embolism | Air embolism refers to the presence of air in the vascular system and occurs when air is introduced into the venous system and travels to the right ventricle and/or pulmonary circulation. An air embolism is reported to occur more frequently during catheter removal than during insertion, and the administration of up to 10 ml of air has been proven to have serious and fatal effects. Small air bubbles are tolerated by most patients.

Signs and symptoms of an air embolism include sudden shortness of breath, continued coughing, breathlessness, shoulder or neck pain, agitation, feeling of impending doom, lightheadedness, hypotension, wheezing, increased heart rate, altered mental status, and jugular venous distension. Treatment: Occlude source of air entry. Place patient in a Trendelenburg position on the left side (if not contraindicated), apply oxygen at 100%, obtain vital signs, and notify physician promptly. To avoid air embolisms, ensure drip chamber is one-third to one-half filled, ensure all IV connections are tight, ensure clamps are used when IV system is not in use, and remove all air from IV tubing by priming prior to attaching to patient. |

||

| Catheter embolism | A catheter embolism occurs when a small part of the cannula breaks off and flows into the vascular system. When removing a peripheral IV cannula, inspect tip to ensure end is intact. | ||

| Catheter-related bloodstream infection | Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CR-BSI) is caused by microorganisms that are introduced into the blood through the puncture site, the hub, or contaminated IV tubing or IV solution, leading to bacteremia or sepsis. A CR-BSI is a nosocomial preventable infection and an adverse event.

CR-BSI is confirmed in a patient with a vascular device (or a patient who had such a device in the last 48 hours before the infection) and no apparent source for the infection other than the vascular access device with one positive blood culture. Treatment: IV antibiotic therapy To avoid CR-BSI, perform hand hygiene prior to care and maintenance of an IV system, and use strict aseptic technique for care and maintenance of all IV therapy procedures. |

||

| Data source: Fraser Health Authority, 2014; Fulcher & Frazier, 2007; McCallum & Higgins, 2012; Perry et al., 2014 | |||

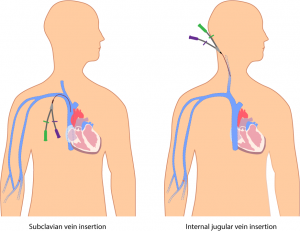

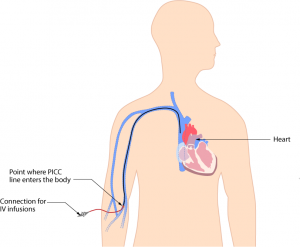

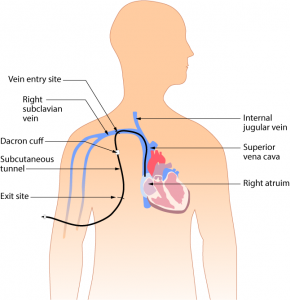

Central Venous Catheters

A central venous catheter (CVC) (see Figure 8.2), also known as a central line or central venous access device, is an intravenous catheter that is inserted into a large vein in the central circulation system, where the tip of the catheter terminates in the superior vena cava (SVC) that leads to an area just above the right atrium. CVCs have become common in health care settings for patients who require IV medication administration and other IV treatment requirements. CVCs can remain in place for more than one year. Some CVC devices may be inserted at the bedside, while other central lines are inserted surgically. Central lines are inserted by a physician or specially trained health care provider, and the use of ultrasound guided placement is recommended to reduce time of insertion and complications (Safer Healthcare Now, 2012).

A CVC has many advantages over a peripheral IV line, including the ability to deliver fluids or medications that would be overly irritating to peripheral veins, and the ability to access multiple lumens to deliver multiple medications at the same time (Fraser Health Authority, 2014). Central venous catheters can be inserted percutaneously or surgically through the jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins, or via the chest or upper arm peripheral veins (Perry et al., 2014). Femoral veins are not recommended, as the rate of infection is increased in adults (CDC, 2011; Safer Healthcare Now, 2012). To have a CVC inserted or removed, an order by a physician or nurse practitioner must be obtained. Site selection for a CVC may be based on numerous factors, such as the condition of the patient, patient’s age, and type and duration of IV therapy.

The majority of patients in an ICU will have a CVC to receive fluids and medications. A chest X-ray is given to determine correct placement before inserting, or to confirm a suspected dislodgement (Fraser Health Authority, 2014). An IV pump must be used with all CVCs to prevent complications.

CVCs are typically inserted for patients requiring more than six days of intravenous therapy or who:

- Require antineoplastic medications

- Are seriously or chronically ill

- Require vesicant or irritant medications

- Require toxic medications or multiple medications

- Require central venous pressure monitoring

- Require long-term venous access or dialysis

- Require total parenteral nutrition

- Require medications with a pH greater than 9 or less than 5, or osmolality of greater than 600mOsm/L

- Have poor vasculature

- Have had multiple PIV insertions/attempts (e.g., two attempts by two different IV therapy practitioners)

A central line is made up of lumens. A lumen is a small hollow channel within the CVC tube. A CVC may have single, double, triple, or quadruple lumens (Perry et al., 2014). Depending on the type of CVC, it may be internally or externally inserted, and may have an open-ended or valved tip. Open-ended devices are those in which the catheter tip is open like a “straw.” These have a higher risk for complications, such as hemorrhage, air embolism, and occlusion from fibrin or clots. Valved devices are those in which the tip is configured with a three-way pressure-activated valve (Perry et al., 2014). It is important to know what type of central line is being used, as this will impact how to care for and manage the equipment for specific procedures. Table 8.3 lists various types of central lines.

CVCs have specific protocols for accessing, flushing, disconnecting, and assessment. All health care providers require specialized training to care for, manage complications related to, and maintain CVCs as per agency policy. Never access or use a central line for IV therapy unless trained as per agency policy. For more information on CVC care and maintenance, see the suggested online reference list at the end of this chapter.

Health care providers should assess a patient with a central line at the beginning and the end of every shift, and as needed. For example, if the central line has been compromised (pulled or kinked), ensure it is functioning correctly. Each assessment should include:

- Type of CVC and insertion date: reason for CVC

- Dressing: is it dry and intact?

- Lines: secure with stat-lock, sutures, or Steri-Strips?

- Review: patient still requires a CVC?

- Insertion site: free from redness, pain, swelling?

- Positive pressure cap: attached securely?

- IV fluids: running through an IV pump?

- Lumens: number of lumens and type of fluids running through each?

- Vital signs: fever?

- Respiratory/cardiovascular check: any signs and symptoms of fluid overload?

See Table 8.4 for a list of complications, signs and symptoms, and interventions.

|

Complication |

Signs and Symptoms |

Interventions | |||||||||||||||

| Pulmonary edema | Also known as fluid overload (circulatory overload); characterized by decreased oxygen saturation, increased respiratory rate, fine or coarse crackles at lung bases, restlessness, breathlessness, dyspnea, coughing up pinky frothy sputum. | Accurate fluid balance assessments, monitor electrolytes and vital signs, provide chest auscultation, elevate head of bed, administer oxygen and diuretic therapy | |||||||||||||||

| Mechanical complications | A mechanical complication that mainly occurs during insertion of the CVC due to failure to correctly place the catheter, which may lead to asystolic cardiac arrest, bleeding, subcutaneous hematoma, hemothorax, catheter mal-position, or pneumothorax. These complications are usually detected at the time of insertion. | Treatment will be specific to the complication. | |||||||||||||||

| Catheter-related bloodstream infection | Infection is a common complication of indwelling CVCs in patients with a vascular device and no apparent source for the bloodstream infection other than the device. Confirmed with one positive blood culture in patients who have had a vascular device implanted within the last 48 hours.

Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CR-BSI) is caused by microorganisms that are introduced into the blood through the puncture site, the hub, or contaminated IV tubing or IV solution, leading to bacteremia or sepsis. A CR-BSI is a nosocomial preventable infection and an adverse event. Systemic: elevated temperature, flushed, headache, malaise, tachycardia, decreased BP, and additional signs and symptoms of sepsis |

Strict hand-washing, aseptic technique for all procedures, close monitoring of vital signs, strict protocols for dressing, tubing and cap changes, blood cultures as required, IV antibiotic therapy, remove/replace catheter, prevent contamination of hub | |||||||||||||||

| Infection at insertion site | Insertion site may become red, tender, swollen, or have purulent drainage. Monitor blood work and temperature. | Notify physician, clean area using strict aseptic technique, send C & S swab (swab for bacterial wound culture) as per policy | |||||||||||||||

| Catheter-related thrombosis | Catheter-related thrombosis (CRT) is the development of a blood clot related to long-term CVC use. It mostly occurs in the upper extremities and can lead to further complications, such as pulmonary embolism, post-thrombotic syndrome, and vascular compromise. Symptoms include pain, tenderness to palpation, swelling, edema, warmth, erythema, and development of collateral vessels in the surrounding area. Most CRTs are asymptomatic, and prior catheter infections increase the risk for developing a CRT. | Routine flushing with positive pressure, vital signs, repositioning, IV bolus, notify physician, venogram/X-rays likely; will require anticoagulant therapy and possible removal of the CVC | |||||||||||||||

| Air embolism | An air embolism is the presence of air in the vascular system and occurs when air is introduced into the venous system and travels to the right ventricle and/or pulmonary circulation. An air embolism can occur during CVC insertion, while catheter is in place, or at time of removal. Administration of up to 10 ml of air has been proven to have serious effects, and is sometimes fatal. Tiny air bubbles are tolerated by most patients.

Signs and symptoms of an air embolism include sudden shortness of breath, continued coughing, breathlessness, shoulder or neck pain, agitation, feeling of impending doom, lightheadedness, hypotension, wheezing, increased heart rate, altered mental status, and jugular venous distension. The effects of air embolism depend on the rate and volume of air introduced.

|

Occlude source of air entry. Place patient in a Trendelenburg position on the left side (if not contraindicated), apply oxygen at 100%, obtain vital signs, and notify physician promptly.

To avoid an air embolism, ensure drip chamber is one-third to one-half filled, ensure all IV connections are tight, ensure clamps are used when IV system is not in use, and remove all air from IV tubing by priming prior to attaching to patient. |

|||||||||||||||

| Occlusions of CVC (mechanical or thrombus) | Occlusions may be mechanical (pinch-off syndrome, due to an internal pinching of the central line between the first rib and clavicle), caused by medication (unplanned/accidental precipitation in the IV line), or from parenteral nutrition (may leave a lipid residue inside the catheter). Thrombus formation (fibrin sheath around the tip of the catheter) may occur as soon as 24 hours after CVC is inserted. Thrombotic occlusions are responsible for approximately 58% of all occlusions. In addition to causing catheter dysfunction, thrombotic occlusions can lead to catheter-related thrombosis. Signs include sluggish flow rate, inability to flush or infuse medications, and frequent downstream occlusion alarms on the EID. | Follow agency-specific guidelines for managing various types of occlusions. Thrombolytic therapy may be initiated.

Do not flush against resistance, flush well between medications, and always flush using positive pressure through a positive pressure cap. |

|||||||||||||||

| Damage to CVC line | CVCs may become broken or cracked. Assess for pinholes, cracks, or tears during routine care. Assess for drainage after routine care.

Avoid using sharp objects around CVCs, and only use a needleless device when accessing a central line. |

Clamp immediately and seal with a sterile, occlusive dressing to prevent an air embolism, bleeding, or a CR-BSI. The CVC may be repaired or replaced. Notify health care provider promptly. Repair should only be completed by a trained CVC specialist. | |||||||||||||||

| Catheter migration | Patient may experience dysrhythmias caused by tip of the catheter moving from original position to an unwanted position. Migration may occur due to increased intrathoracic pressure due to coughing, change in body position, or physical movement (of the arms), sneezing, or weightlifting. | Call physician and stop all fluid infusions. You may need to pull back on tubing and X-ray CVC again for placement confirmation.

Tape catheter securely using tape and devices. Do not pull on central lines; prevent IV lines from being caught on other equipment. |

|||||||||||||||

| Data source: Baskin et al., 2009; BCIT, 2015a; Brunce, 2003; Fraser Health Authority, 2014; Perry et al., 2014; Prabaharan & Thomas, 2014 | |||||||||||||||||

Critical Thinking Exercises

- What is the difference between a non-tunnelled (percutaneous) catheter and a tunnelled catheter?

- Name three advantages and three disadvantages of a central line.