Poetry

17 “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes (Free Verse)

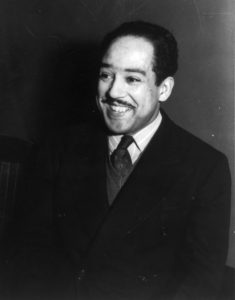

Biography

James Mercer Langston Hughes was born February 1, 1901, in Joplin, Missouri. For many years, he lived an unsettled life. His father deserted the family while Langston was still an infant. Langston was sent to Lawrence, Kansas, to be raised by his grandmother. When he reached adolescence, he rejoined his mother and her new husband, now living in Lincoln, Illinois, but soon to relocate to Cleveland, where Langston attended high school. He spent time with his father, now a lawyer in Mexico, who agreed to help finance Langston’s education at Columbia University.

He dropped out of Columbia in 1922, feeling alienated as one of the few black students there. He travelled and worked a variety of odd jobs. He was a busboy at a Washington hotel, where he encountered the poet Vachel Lindsay. He shared some of his work with Lindsay, who, impressed, helped him publish his first book of poems, The Weary Blues, which he had been writing since he was a high school student.

Hughes returned to university, attending the historically black Lincoln University and graduating in 1929. He travelled some more, notably to the Soviet Union, because he was optimistic about the social justice—the racial equality, especially—that communism promised. He returned to the US, settling now in the Harlem borough of New York City, the centre for a renaissance in African-American culture. For the rest of his life, he was a productive man of letters, the author of poetry collections, short stories, novels, plays, and children’s books.

Hughes is generally regarded as the finest writer of the Harlem Renaissance. After the First World War, the American economy boomed, and thousands of African-Americans migrated north to find work in the rapidly expanding manufacturing sector. Many settled in the Harlem neighbourhood of New York. Economic prosperity helps breed artistic expression, and scores of talented black poets began to publish highly acclaimed collections. The Harlem Renaissance helped spawn the civil rights movement of the 1950s.

Hughes died on May 22, 1967, after an unsuccessful operation to treat prostate cancer.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

Read “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes online.

Analysis

Theme

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” is a black pride poem. In just thirteen free verse lines, the author reviews milestones in the history of his race. Hughes presents a catalogue of the rivers the “Negro” speaker—who is a kind of Everyman for the black race—has known. The great rivers of West Asia and Africa—the Euphrates, the Congo, and the Nile—are naturally featured, but so, too, near the end of the poem is the Mississippi, which he heard “singing,” “when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans.” Hughes’s purpose is to extol the contributions of his race to world history.

Form

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” is a free verse poem, one that will have rhythm and may have rhyme but not a recurring rhythm pattern or rhyme scheme. Note the varying lengths of the lines on the page, usually a marker for a free verse poem.

The genius of the free verse form of the poem lies in the way it mimics the movement of a river. A river flows in free verse. A three-word line winds into an eighteen-word line. An eight-word line forms its own stanza, the waters moving slowly, then a five-line stanza picks up the pace, with a series of subject-verb, imagery-rich lines—“I bathed,” I built,” “I looked,” “I heard”—as the river of the poem seems to straighten out. The ending reaffirms the spiritual affinity of the black race with the natural world, as the narrator repeats his earlier declaration that his soul “has grown deep like the rivers.”

Figurative Language

Hughes’s use of metaphor reaffirms the connection between the human and natural worlds, symbolized by the rivers and essential to the poem’s theme. The metaphor in the poem’s first line compares rivers to the “flow of human blood in human veins.” The simile that first appears in the fourth line and is repeated in the last line reaffirms this connection, especially as it connects with black history: “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

Hughes also uses imagery effectively, especially in the ninth and tenth lines. He is describing Abe Lincoln sailing down the Mississippi River to its delta in New Orleans, and he writes of the river, “I’ve seen its muddy / bosom turn all golden in the sunset.”

Context

Hughes revealed that he wrote this poem in 1920, when he was crossing the Mississippi River on a train, on his way to Mexico to visit his father. He included it in his volume of poetry The Weary Blues, published in 1926. It is among Hughes’s most popular and anthologized poems.

Related Activities and Questions for Study and Discussion

Activities

- Read Glynn Wilson’s essay “The Ultimate Metaphor: Life Is Like a River” online. Compare her essay with Hughes’s poem.

- Read some of the poems by other leading Harlem Renaissance authors, including Countee Cullen and Jean Toomer.

- Hear Hughes read some of his poetry.

Media Attributions

- Langston Hughes © Jack Delano is licensed under a Public Domain license