Appendix D: Brave New World Casebook

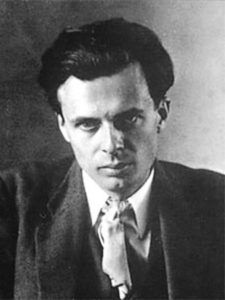

Biography: Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley was descended from two eminent Victorian families—he was the grandson of noted biologist and writer on science, Thomas Henry Huxley, grandnephew of Matthew Arnold, and nephew of Victorian novelist Mary Augusta Ward (who wrote under her married name Mrs. Humphry Ward), Arnold’s niece. His unusual Christian name commemorates a major character, Aldous Raeburn, in the novel Marcella, which Mrs. Ward published in the year of Huxley’s birth, 1894.

Born in Godalming, Surrey, England, he received his first schooling from his mother, Julia Arnold Huxley. He then moved on to Hillside Preparatory School, Eton, and eventually, Balliol College, Oxford, taking a first in English in 1916. Two early blows—the death of his mother when he was only nine, and an attack of keratitis while he was a student at Eton, which left him nearly blind for the rest of his life—may have sharpened his tendency toward introversion. Certainly the latter affliction precluded a career in science, paving the way for a life in letters.

In the course of his long literary career, Aldous Huxley published poetry collections, plays, essays, short fiction, travel narratives, biography, and criticism, but, like George Orwell, author of Nineteen-Eighty-Four, he is best remembered as the author of a hugely influential utopian satire. Both men used the genre more than once. Brave New World began, like Orwell’s Coming Up for Air, as a response to H.G. Wells’s utopia, Men Like Gods (1923), and Huxley later wrote two more utopian-dystopian novels: Ape and Essence (1948) and Island (1962).

Although Huxley felt that he was not a “born novelist, but an essayist who writes novels,” he became an innovative fictional stylist, effectively using cinematic montage technique for the purpose of exposition in the third chapter of Brave New World, thereby sparing the reader from that major defect of most utopian novels—the tedious guided tour of utopian schools, hospitals, and factories. With his use of montage and intertextuality, Huxley did for the novel what Eliot had done for modern poetry in The Waste Land 10 years earlier. Like Eliot, Huxley often uses multiple references to canonical works. In Brave New World, his 50 allusions to Shakespeare help develop theme. He also incorporates ideas of fashionable Freudians, such as Ernest Jones and his interpretation of Hamlet to deepen the sense of the Savage’s sexual repression. At opportune moments, he echoes key lines from Gray’s “Elegy” and “Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton” to underscore the ignorance-is-bliss theme and key images that recall the utilitarian schoolroom in Dickens’s Hard Times. Nor does he hesitate to use bathos: the deliberate contrasting of high culture with popular culture. Excerpts from fictional advertising jingles and popular 1920s-era romances, such as Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks, satirize the contemporary lowering of musical and literary standards.

One notes a gradually emerging social conscience in Huxley at the time of his writing Brave New World. In fact, his satiric description of the reified workers in a dystopian factory was based on his visit to a Lucas automotive parts factory in Birmingham the previous spring.

In Brave New World, the novel’s most sympathetic character, Helmholtz Watson, like Wordsworth on Westminster Bridge, finds the silence of the sleeping metropolis to be eloquent: the very absence of the numinous in the wholly materialistic state begins, paradoxically, to suggest a presence. Watson is one of the first in what becomes a steady string of protagonists in his future novels who advocate what Huxley called “the great central technique, which traces the art of obtaining freedom from the fundamental human disability of egotism … repeatedly described by the mystics of all ages and countries.” His final utopian novel, Island (1962), is, in fact, Huxley’s final word on the subject of how to construct the good society. He died in Hollywood on November 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Brave New World

Here is where you can read the full text of Brave New World.

Activities

Brave New World

Sir Thomas More coined the word “utopia” in his fictional work Utopia, first published in Latin in 1516. He created the word by combining the Greek prefixes “ou”and “eu” with the suffix “topos.” Define the two Greek prefixes and the Greek suffix, and then show how the concept of utopia is inherently playing with two different places.

Epigraph—What is an epigraph? Huxley uses the following quotation from Nicolas Berdiaeff, Un nouveau moyen age 1927, p. 262:

Les utopies apparaissent comme bien plus réalisable qu’on ne le croyait autrefois. Et nous nous trouvons actuellement devant une question bien autrement angoissante: Comment éviter leur réalisation définitive? Les utopies sont réalisables. La vie marche vers les utopies. Et peut-être un siècle nouveau commence-t-il, un siècle où les intellectuels et la classe cultivée rêveront au moyens d’éviter les utopies et de retourner à une société non utopique, moins “parfaite” est plus libre.

[English translation: Utopias appear to be more realizable than we used to believe. And we now find ourselves facing a deeply troubling question: How to avoid their definitive realization? Life marches towards utopia. And maybe a new century will begin, a century where the intellectuals and cultivated classes will dream of ways to avoid utopias and to return to a non-utopian society, less perfect and more free.]

Chapter 1

- Notice the two sentence fragments with which Huxley begins the novel. If a thirty-four-storey building is described as “squat,” then what kind of irony is Huxley using here?

- Look up the word “identity” in a good dictionary. What aspect of the word is central to the world state’s philosophy?

- Compare Huxley’s use of colour imagery in this chapter with that of Dickens in the second chapter of Hard Times.

- Do Alphas and Betas undergo Bokanovsky’s technique?

- Describe how the government of the brave new world resembles that of H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia (1905) or that of Men Like Gods (1923).

- Write a brief essay in which you speculate that Huxley borrowed ideas from Wells, especially Chapters 14, 15, and 20 from his dystopia The Sleeper Awakes.

Chapter 2

- What kind of irony does Huxley use when he gives the following line to the D.H.C.: “The greatest moralizing and socializing force of all time”?

- What is the status of the English language in A.F. 632? French?

- Compare the first two chapters of Dickens’s Hard Times (“The One Thing Needful” and “Murdering the Innocents”) with the first two chapters of Brave New World. How is Henry Foster like Bitzer? What values do they share? Which kind of education do both dystopias—i.e., the brave new world and Dickens’s Coketown—prefer: particular or general education? Or, in other words, vocational or liberal education?

Chapter 3

- What is the world’s population in 632 A.F.?

- Brave New World, like T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, uses montage technique as in film. This device is especially evident in Chapter 3, where settings and character shift with no transition devices being offered to the reader. Scenic cuts become faster as the chapter advances. In the first two and a half pages of Scene 1, in Chapter 3, we observe the D.H.C. and his students outside the Hatchery and Conditioning Centre, watching the children at play—first, Centrifugal Bumple-Puppy, then erotic play; followed by the introduction of the World Controller, Mond; then to indicate a shift of scene and character, comes a double space. Then we see Henry Foster snubbing Bernard Marx at the embryo store as Lenina enters. Scenes shift between the D.H.C. and Mond’s history lesson and the dialogue between Foster, the Assistant Predestinator. Try placing an M for Mond at the beginning of each of his scenes, L for Lenina’s, as they counterpoint, and notice how gradually the interval between Mond’s words and Lenina’s gets reduced. Sometimes only one line intervenes until Mond or Lenina/Fanny take up their lines.

- Give one example of Mond’s being depicted as an ironic Christ figure—it occurs near the end of the chapter. How is Mond an ironic Christ figure?

- How is Mond like one of H.G. Wells’s samurai in his A Modern Utopia?

- In a brief essay, compare Huxley and Eliot’s use of juxtaposition of past versus present.

- After reading Mond’s history lesson in Chapter 3, give the chief reason for the creation of the brave new world.

- The utopian society of the brave new world apparently minimizes the problems associated with old age through hormone treatments (Violent Passion Surrogates, gonadal hormones). Look up the scientists Serge Voronoff (1866–1951) and Eugen Steinach (1861–1944). Huxley refers throughout the novel to ductless glands, adrenals, pituitary glands, internal and external secretions, and gonads. He is almost certainly referring to the rejuvenation theories of Steinach and Voronoff. (Interestingly, late in his life, W.B. Yeats underwent such rejuvenation therapy and reported positive results.) By 1929, the Marx Brothers famously alluded to this rejuvenation fad in their song “Monkey Doodle-Doo” in their film The Cocoanuts: “Let me take you by the hand / Over to the jungle band / If you’re too old for dancing / Get yourself a monkey gland / And then let’s go, my little dearie, there’s the Darwin theory…”

- You might consider writing an essay on Huxley’s use of rejuvenation therapy in BNW.

Chapter 4

- List the uniform colour for Gammas, Deltas, and Epsilons.

- Why is Community Singing encouraged in the brave new world?

- Notice the special meaning for the word “Corporation.” List a few examples and then clarify what a Corporation is. What European state was known as a “corporate state” between the wars? Is the brave new world a “corporate state”?

- Before her date with Bernard, Lenina rushes to meet Henry Foster, fearing her lateness will annoy Henry, who is a stickler for punctuality. His efficiency-expert attention to time introduces the satire on industrial rationalization as championed by F.W. Taylor, a time-and-motion engineer, dubbed “the father of scientific management,” and whose books greatly influenced Ford. See first Then, look at the following article: “Sophistication of Mass Production”.

Chapter 5

- The chapter begins with several allusions to Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” Read the poem, especially the first 50 lines.

- Make a list of words that Huxley borrows from Gray here. Write a brief essay on the thematic use Huxley makes of the contrast between Gray’s poem and the novel.

Chapter 6

- Contrast what Henry Foster expects from his relationship with Lenina with what Bernard Marx wants from her.

- What is the main conflict in this chapter? Between which characters?

- A key symbol is the electric fence separating “civilization from savagery”:Uphill and down, across the deserts of salt or sand, through forests, into the violet depth of canyons, over crag and peak and table-topped mesa, the fence marched on and on, irresistibly the straight line, the geometrical symbol of triumphant human purpose. And at its foot, here and there, a mosaic of white bones, a still unrotted carcase dark on the tawny ground marked the place where deer or steer, puma or porcupine or coyote, or the greedy turkey buzzards drawn down by the whiff of carrion and fulminated as though by a poetic justice, had come too close to the destroying wires. “They never learn,” said the green-uniformed pilot, pointing down at the skeletons on the ground below them. “And they never will learn,” he added and laughed, as though he had somehow scored a personal triumph over the electrocuted animals.This image needs to be examined carefully. Typically, the straight line symbolizes human reason, science. Notice that man has conquered nature, and that the animals are killed by the voltage in the man-made fence. Just before he was writing Brave New World, Huxley was highly critical of Le Corbusier, the famous French/Swiss architect. Look up Le Corbusier on Wikipedia. In his foreword to Urbanisme (Englist translation, The City of Tomorrow) (1929), he said, “A curved road is a donkey path; a straight road is a road for men.” One thinks here of the myth of Pandora’s box and of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden for eating of the fruit of the tree of knowledge. Pride is the common denominator in both myths.Look at the “Forays into Urbanism 1922–1929″ section of the site mentioned above. Pay particular attention to the photo of Le Corbusier’s sketch of a city for three million people, with its 60-storey buildings, rooftop helipads, etc. Note also that Le Corbusier hoped that politically minded industrialists in France would lead the way with their efficient Taylorist and Fordist strategies adopted from American models to reorganize society. In this new industrialist spirit, Le Corbusier began a new journal called L’Esprit Nouveau that advocated the use of modern, industrial techniques and strategies to transform society into a more efficient environment with a higher standard of living on all socioeconomic levels. He forcefully argued that this transformation was necessary to avoid the spectre of revolution that would otherwise shake society. His dictum “Architecture or Revolution,” developed in his articles in this journal, became his rallying cry for the book Vers une architecture (“Towards an Architecture,” translated into English as Towards a New Architecture), which comprised selected articles from L’Esprit Nouveau between 1920 and 1923.Huxley had a long-standing aversion to Le Corbusier’s urban style, calling him “an enemy of privacy,” and BNW is an attack on his kind of futuristic city. Is Huxley warning against human pride here, our tendency to try to dominate nature, to improve upon it as Henry Foster is so eager to demonstrate?

- You might consider writing an essay on Huxley’s critique of modernist architects such as Le Corbusier.

Chapter 7

- The expression “Cleanliness is next to godliness” is not from the Bible. Who popularized the adage?

- What is John’s mother Linda’s relationship to nature and technology?

- Explain how Linda’s allusion to the Chelsea Abortion Centre is an example of bathos. Note that Sir Christopher Wren’s classically designed Chelsea Hospital has now become an abortion centre.

- What key information concerning the D.H.C. is divulged in this chapter?

Chapter 8

- How does young John react to the relationship between his mother and Popé, the man who gave John a tattered copy of Shakespeare’s complete works?

- John learns to read, but the only book he reads besides Linda’s technical manuals is The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Immediately, the descriptions in Hamlet and other plays provide John with the negative vocabulary and another perspective with which to view Popé and Linda’s sexual behaviour: “Nay, but to live / In the rank sweat of an enseamed bed, / Stewed in corruption, honeying and making love / Over the nasty sty.” (Hamlet, 3.4.91–94).

- In Hamlet, Shakespeare depicts women as either madonnas (innocents like Ophelia before she falls out of Hamlet’s favour) or else whores (Gertrude with Claudius or Ophelia after her rejection of Hamlet’s love). John will soon begin to idealize Lenina, who is so unlike his aging mother. John had earlier loved the Indian maid Kiakimé, but at age 16, his heart was broken as she married another—a young, full-blooded Zuñi man, not an outsider like John. John was also an outsider to the rites and mysteries discussed in the kiva, so the essence of John’s experience is rejection. He will be an outsider in both communities, because of his different race in the reserve, and because of his different values in the brave new world.

- Notice Freud’s articulation of the whore–madonna theory.

- Look up Ernest Jones, Freud’s biographer. Then read this article titled “The Sphinx of Modern Literature”, which explains how Jones interpreted Shakespeare’s Hamlet in light of the Freudian Oedipus complex.

Chapter 9

- Why do you think Mond allows John and Linda to come with Bernard and Lenina to “civilization”?

- What is the attitude to romantic love in the brave new world?

Chapter 10

- What is the significance of the perfectly synchronized clocks in all 4,000 rooms of the Centre? How does this image link to F.W. Taylor?

- In what ways does the brave new world resemble a beehive or ant colony?

Chapter 11

- What scene causes John to repeat Miranda’s famous phrase “O, brave new world,” and how is his meaning different from the first time he says this at the end of Chapter 8? In what later chapter does John utter these lines yet again? Clarify the irony with respect to John’s three separate quotations of Miranda’s words.

- Why is it more difficult, according to Miss Keate, to educate upper-caste, one-egg, one-adult students?

Chapter 12

- What is the central paradox in the poem Helmholtz writes? In what way does it resemble William Wordsworth’s sonnet “Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802”?

- What does it have in common with T.S. Eliot’s “Preludes”?

- In a brief essay, analyze Helmholtz’s 24-line poem, beginning “Yesterday’s committee…”

Chapter 13

- Discuss the significance of the promising Alpha-minus administrator’s dying of trypanosomiasis. Try to relate it to one of the main hypnopaedic maxims of BNW.

- What does John Savage mean when he says “some kinds of baseness are nobly undergone”?

- In what way is Lenina atavistic?

- When Lenina grabs John and kisses him, what does he experience and why?

- Describe the change in the image patterns found in the poetic lines that John suddenly starts to quote from Shakespeare. Account for the sudden change in the kinds of images.

Chapter 14

- What is the earliest entry in the Oxford English Dictionary for the word “television”?

- Whose name does Linda call out when John visits her in the hospital?

Chapter 15

- How does the historic soma and its use differ from the soma of BNW?

Chapter 16

- “Chapter 16 shows Bernard Marx at his worst.” Do you agree or disagree?

- What was the Cyprus experiment?

- In the discussion scene between Mond and John, it is hard not to think of another poem by Thomas Gray here, “Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College.” In that poem, Gray contrasts the thoughtless days of youth before the pain of adulthood are known. “Regardless of their doom / The little victims play! / No sense have they of ills to come, / Nor care beyond today.” (ll. 51–54). As Mond knows, and as John must learn, the brave new world eliminates all the ills that Gray attributes to adulthood: the Passions of Anger, Fear, Shame, pining Love, Jealousy, Envy, Care, Despair, Sorrow, Ambition, Death, Poverty, and slow consuming age. The inhabitants of Mond’s stable, controlled society, unlike men, are not “condemned alike to groan.” How can Mond’s position be partly summed up by the last stanza (lines 91–100)?

Chapter 17

Huxley was indebted to Dostoevsky’s famous Grand Inquisitor chapter from The Brothers Karamazov in Chapters 16 and 17, with John resembling Dostoevsky’s Christ figure, and Mond representing his Grand Inquisitor.

The essence of the conflict between John and Mond is whether happiness (Mond’s goal) is the chief goal in human society or whether it is some form of heightened consciousness/freedom for each person (John’s goal). Dostoeivsky used Satan’s triple temptation of Christ in the wilderness as his starting point. [See Matthew: ch. 4]

- In the context of the Grand Inquisitor, why do you think Mond encourages the Fordian religion? Why does the brave new world bother with religion at all?

Chapter 18

- Do you consider Bernard Marx a static or a dynamic, changing character? That is, does he grow or change during the novel? Is he any different in his final appearance in Chapter 18?

- Who is Darwin Bonaparte and who might be his modern equivalent?

- In the last scene, what might the references to the compass points suggest?

Overview

- The 1980s film version of Brave New World (three hours). All rights reserved. This film is a reasonably good adaptation of the novel, if rather long. The script was written by Robert E. Thompson, who received an Oscar nomination for his scenario of the film They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

- BBC Radio Brave New World documentary (forty-five minutes). An outstanding discussion of numerous aspects of the novel with three world experts on 20th-century British literature. You must download the audio file to listen.

- BBC Radio Modern Utopias podcast (forty-five minutes).

- Brave New World Wikipedia entry. An excellent overview of plot, character, and contexts.

- Margaret Atwood’s essay on Brave New World. This is substantially the same essay as her introduction to Brave New World in the Vintage edition.

Disciplinary Readings

History Concentration

Ford, Henry. My Life and Work. 1922. Retrieved from http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=7213

Huxley, Aldous. “Sight Seeing in Alien Englands.” Nash’s Pall Mall Magazine. June. 1931.

This is a companion essay to Brave New World in which Huxley describes his visits to Alfred Mond’s chemical factory in the north of England, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), and to the Lucas Electrical Parts factory in Birmingham.

Meckier, Jerome. “Aldous Huxley’s Americanization of the ‘Brave New World’ Typescript.” Twentieth Century Literature vol. 48.4, 2002, pp. 427-460. http://somaweb.org/w/sub/Americanization.html

Primarily a historical approach to the novel.

MIRANDA: a hypertext of Huxley’s Brave New World Huxley.net. Web. 2010, http://www.huxley.net/miranda/history.html

Links to political figures important to BNW.

René Fülop-Miller. The Mind and Face of Bolshevism. G. P. Putnam S Sons Ltd. London, 1927, https://archive.org/details/mindandfaceofbol015704mbp

Huxley reviewed this anti-communist book shortly before he wrote BNW. It is an important source for the satire on communism.

Sexton, James. “Aldous Huxley’s Bokanovsky” Science Fiction Studies Science Fiction Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, 1989, https://www.depauw.edu/sfs/notes/notes47/notes47.html

A short essay on the source of the name “Bokanovsky.” Click on “Notes and correspondence”

Sexton, James. “Brave New World and the Rationalization of Industry [PDF].” English Studies in Canada 12, 1986, pp. 424-436, https://opentextbc.ca/provincialenglish/wp-content/uploads/sites/297/2019/08/brave-new-world-and-the-rationalization-of-industry-3.pdf

This paper discusses Huxley’s satire on communism and capitalism in the novel. It would be useful for research focusing on history and/or business.

Sexton, James. “‘Brave New World,’ The Feelies, and Elinor Glyn. [PDF]” English Languages Notes, vol 35, No. 1, Sept 1997, pp. 35-38, http://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2014/09/RevdBrave-New-World-The-Feelies-and-Elinor-Glyn.pdf

Discusses the uses Huxley made of various sources, such as Shakespeare’s Othello and Elinor Glyn’s novel It.

Sexton, James. Dickens’ Hard Times and Dystopia. The Victorian Web. 8 June 2007. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/hardtimes/sexton1.html

This essay discusses Charles Dickens’ “condition of England” novel Hard Times as a source for Brave New World.

Psychology Concentration

Newman, Bobby. “Brave new world revisited revisited: Huxley’s evolving view of behaviorism.[PDF]” The Behavior analyst vol. 15, no. 1, 1992, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2733409/pdf/behavan00027-0062.pdf

Valuable discussion of Huxley’s changing attitude to behaviorism in BNW and later works. Psychology

Real, Willie. “Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World as a Parody and Satire of Wells, Ford, Freud and Behaviourism [PDF]” AHA 8, https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2014/06/WReal-BNW-as-satire-Ford-freud-watson-wellsaha8Real2.pdf

A wide-ranging discussion of Huxley’s satire on the ideas of key figures in psychology.

Biology Concentration

Congdon, Brad. ““Community, Identity, Stability”: The Scientific Society and the Future of Religion in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.” ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 37 no. 3, 2011, pp. 83-105. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/esc/index.php/ESC/article/view/24890

This paper is quite wide-ranging but will be particularly helpful for students wanting to concentrate their research on biological aspects of the novel. N.B. Type “congdon” in author box once at the ESC site.

Haldane, J. B. S. 1892-1964. Daedalus, Or, Science and the Future: A Paper Read to the Heretics, Cambridge, on February 4th, 1923. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, London, 1925, https://archive.org/details/Daedalus-OrScienceAndTheFuture

This paper by noted biologist Prof. Haldane, a friend of Huxley’s, discusses concepts such as ectogenesis and others topics central to Brave New World.

Huxley, Julian. “The Tissue-Culture King.” Cornhill Magazine vol. 60 (New Series), no. 358, April 1926, http://www.revolutionsf.com/fiction/tissue/

A science-fiction story by Huxley’s brother, Sir Julian Huxley, written in 1927. This story discusses scientific ideas also found in Brave New World.

Anthropology Concentration

“Los Hermanos Penitentes.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 22 July, 2019, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11635c.htm

Franklin, Benjamin. “Remarks on the Savages of North America.” The Bagatelles from Passy. Ed. Lopez, Claude A. New York: Eakins Press. 1967, http://mith.umd.edu//eada/html/display.php?docs=franklin_bagatelle3.xml

Hare, John Bruno. “The Zuñi Religion.” Internet Sacred Text Archive, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20230317224630/https://sacred-texts.com/nam/zuni/

Huxley used some of the Smithsonian reports from Frank Cushing for background source material for Brave New World.

Hough, Walter. Moki Snake Dance. Passenger department, The Santa Fe, 1901, https://archive.org/details/mokisnake00houg

N.B. “Moki” was an early synonym for “Hopi”. Huxley read this pamphlet in 1930 before writing Brave New World. Despite his limited time visiting Aboriginal reservations in the U.S. states of Arizona and New Mexico, he was able to gain further background details for the “Savage Reservation” chapters in the novel by using this and other publications as source material. The Cushing, Hough and the Higdon essays are particularly useful for students wishing to do research with emphasis on Anthropology.

Leon, David Higdon. “Huxley’s Hopi Sources [PDF]”, The 4th International Aldous Huxley Conference, 31 July – 2 August 2008, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Paper presentation. http://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2014/06/Hopi-Sources-with-fnsecond-version.pdf

Meckier, Jerome. “Brave New World and the Anthropologists-primitivism in A.F. 632.[PDF]” Alternative Futures 1.1 1978, pp. 51-69. http://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2014/07/latestmeckier-bnw-anthroroughdraft.pdf

Philosophy Concentration

American Academy of Arts and Letters, “Utopias, Positive and Negative. Aldous Huxley [PDF]” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Second Series. New York, 1963. http://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/?attachment_id=455

Dostoevsky, Fyodor Mikailovich, “The Grand Inquisitor” The Brothers Karamazov, 1880, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8578

This will be useful for students wishing to focus on Chapters 16 and 17 in Brave New World, particularly the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor.

Fremantle, Anne. “A Summary of ‘The Grand Inquisitor [PDF]” Introduction to “The Grand Inquisitor”, New York : Ungar, 1956, http://web.pdx.edu/~tothm/religion/Summary%20of%20The%20Grand%20Inquisitor.pdf

Lewicki, Grzegorz. “Dostoyevsky Extended: Aldous Huxley On The Grand Inquisitor, Specialisation and The Future of Science.” 2008, https://www.academia.edu/218384/Dostoyevsky_extended_Aldous_Huxley_on_Grand_Inquisitor_Specialisation_and_Future_of_Science

Matter, William W. “The Utopian Tradition and Aldous Huxley.” Science Fiction Studies 1975, pp. 146-151. http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/6/matter6art.htm

As the title suggests, this essay discusses Brave New World within a context of previous utopian works, including Plato’s Republic. Click on “Notes and Correspondence” to download the article.

MIRANDA: a hypertext of Huxley’s Brave New World Huxley.net. Web. 2010

Contains numerous sources for Brave New World in downloadable format.

Sexton, James. “Utopias Positive and Negative Afterword [PDF]” http://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/?attachment_id=454

Media Attributions

- Aldous Huxley © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license