Poetry

21 “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning (Dramatic Monologue)

Biography

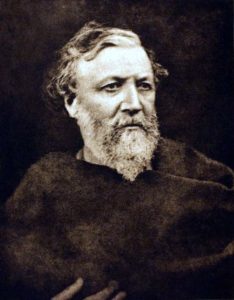

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father worked as a bank clerk and was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning’s education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen, he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship.

At the age of twelve, he wrote a volume of Byronic verse entitled Incondita, which his parents attempted, unsuccessfully, to have published. In 1825, a cousin gave Browning a collection of Shelley’s poetry; Browning was so taken with the book that he asked for the rest of Shelley’s works for his thirteenth birthday, and declared himself a vegetarian and an atheist in emulation of the poet. Despite this early passion, he apparently wrote no poems between the ages of thirteen and twenty. In 1828, Browning enrolled at the University of London, but he soon left, anxious to read and learn at his own pace. The random nature of his education later surfaced in his writing, leading to criticism of his poems’ obscurities.

In 1833, Browning anonymously published his first major published work, Pauline, and in 1840, he published Sordello, which was widely regarded as a failure. He also tried his hand at drama, but his plays, including Strafford, which ran for five nights in 1837, and the Bells and Pomegranates series, were for the most part unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the techniques he developed through his dramatic monologues—especially his use of diction, rhythm, and symbol—are regarded as his most important contribution to poetry, influencing such major poets of the twentieth century as Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and Robert Frost.

After reading Elizabeth Barrett’s Poems (1844) and corresponding with her for a few months, Browning met her in 1845. They were married in 1846, against the wishes of Barrett’s father. The couple moved to Pisa and then Florence, where they continued to write. They had a son, Robert “Pen” Browning, in 1849, the same year Browning’s Collected Poems was published. Elizabeth inspired Robert’s collection of poems Men and Women (1855), which he dedicated to her. Now regarded as one of Browning’s best works, the book was received with little notice at the time; its author was then primarily known as Elizabeth Barrett’s husband.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in 1861, and Robert and Pen Browning moved to London soon after. Browning went on to publish Dramatis Personae (1864), and The Ring and the Book (1868). The latter, based on a seventeenth century Italian murder trial, received wide critical acclaim, finally earning Browning renown and respect in the twilight of his career. The Browning Society was founded in 1881, and he was awarded honorary degrees by Oxford University in 1882 and the University of Edinburgh in 1884. Robert Browning died on the same day that his final volume of verse, Asolando, was published, in 1889.

My Last Duchess

FERRARA[1]

That’s my last Duchess[2] painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I[3] call

That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s[4] hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

5Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said

“Fra Pandolf” by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

10The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

15Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps

Fra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle[5] laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat.”[6] Such stuff

20Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

25Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace—all and each

30Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thanked

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

35This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech—which I have not—to make your will

Quite clear to such a one, and say, “Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let

40Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth,[7] and made excuse—

E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

45Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master’s known munificence

50Is ample warrant that no just pretense

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;[8]

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune,[9] though,

55Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck[10] cast in bronze for me!

Analysis

Theme

The Duke’s speech reveals his character, and from his character emerges the theme of the poem. The Duke’s late wife displeased him, because he thinks she took joy in the simple pleasures of life at the expense of the attention and reverence she should have granted exclusively to him and to his “nine-hundred-years-old name.” His last Duchess chatted with Fra Pandolf, who painted her portrait; she loved the sunset; she loved the bough of cherries the gardener brought her; she loved riding around the estate on her white mule. The Duke believes, on the basis of no evidence, that his Duchess flirted with men. And so he “gave commands / Then all smiles stopped together.” He has her executed. The Duke reveals himself to be pathologically jealous, a product of his own deep-seated insecurities. And herein lies the main theme of the poem: the destructive power of jealousy arising from an arrogance that masks low self-esteem.

Form

“My Last Duchess” is a dramatic monologue. It is a monologue in the sense that it consists of words spoken by one person. It is dramatic in the sense that another person is present, listening to the speaker’s words, which are shared with a wider audience, the poem’s readers. A dramatic monologue is, in a sense, a very short one-act play.

This is a regular verse dramatic monologue, in rhyming couplet iambic pentameter.

Figurative Language

The Duke comes across as a blunt, plain-spoken man, not one to use imagery or metaphor. The striking image of lines 18–19, noting that a painter would have trouble reproducing “the faint / Half-flush that dies along [the Duchess’s] throat,” is in the voice of the artist. It does foreshadow the Duchess’s fate.

The bronze sculpture of Neptune taming a sea horse, which the Duke points out to the Count’s ambassador before they rejoin the other guests, is a symbol of the control the Duke intends to exert upon his new bride. He has an ulterior motive in pointing out the statue.

Irony, as an element of literature, is a behaviour or an event which is contrary to readers’ or audience expectations. We say it is “ironic” when the Chief of Police is convicted of a crime. “My Last Duchess” rings with irony. The Duke condemns his wife’s behaviour but reveals her to be an innocent free spirit. He believes he is an honourable man, acting appropriately in the interest of preserving the integrity of his “nine-hundred-years-old name.” Readers soon understand the truth: the Duke is an insecure control freak and a murderer.

Context

“My Last Duchess” was published in 1842, in Browning’s poetry collection Dramatic Lyrics. Browning was a student of the history, literature, and culture of Renaissance Italy, which is the poem’s setting, though he had not yet eloped with Elizabeth and settled with her in Italy.

Related Activities and Questions for Study and Discussion

Activities

- “My Last Duchess” was published in 1842 and is set in Italy in 1561. Consider how, if at all, the story it tells and the character of the Duke continue to be relevant today.

- Watch a dramatic reading of “My Last Duchess” by Robert Pennant Jones.

- Watch a dramatic reading of “My Last Duchess” by Ed Peed.

Text Attributions

- Biography: “Robert Browning” from poets.org © All Rights Reserved. Biography reprinted with the permission of the Academy of American Poets, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 901, New York, NY, www.poets.org

- “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning is free of known copyright restrictions in Canada.

Media Attributions

- Robert Browning by Cameron, 1865 © Julia Margaret Cameron is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Browning identifies the speaker, who delivers the lines which form the poem. He is Alfonso II, the Duke of Ferrara, a Province in northeast Italy. ↵

- In 1558, Ferrara married 14-year-old Lucrezia de Medici, daughter of the Grand Duke of another Italian province, Tuscany. She died in 1561. She may have died from tuberculosis, but Browning suggests in the poem she was murdered—poisoned or strangled—on the orders of her husband. ↵

- The Duke is based upon Alfonso II, fifth Duke of Ferrara (1533–97). In 1558, he married 14-year-old Lucrezia de’ Medici, who died in 1561 under suspicious circumstances. ↵

- Brother or Friar Pandolf, a fictitious painter from a monastic order. ↵

- Her shawl. ↵

- Perhaps a hint, a foreshadowing, of the Duchess’s death by strangulation. ↵

- Indeed. ↵

- We learn now that the listener is the ambassador for another Duke or, in this case, a Count, whose daughter Ferrara wishes to marry, as long as the dowry is sufficient. (In the interest of historical accuracy, it was more likely Tyrol’s niece whom Ferrara wished to marry.) ↵

- Roman sea god, here depicted as subduing a mythical beast, half horse, half fish. ↵

- An imaginary sculptor. The reference may be an indirect compliment to Ferdinand of Innsbruck, Count of Tyrol, whose daughter Alfonso married in 1565. ↵